原文地址,可见异步IO才真正的强悍。

Before describing select and poll , we need to step back and look at the bigger picture, examining the basic differences in the five I/O models that are available to us under Unix:

-

blocking I/O

-

nonblocking I/O

-

I/O multiplexing (select and poll )

-

signal driven I/O (SIGIO )

-

asynchronous I/O (the POSIX aio_ functions)

You may want to skim this section on your first reading and then refer back to it as you encounter the different I/O models described in more detail in later chapters.

As we show in all the examples in this section, there are normally two distinct phases for an input operation:

-

Waiting for the data to be ready

-

Copying the data from the kernel to the process

For an input operation on a socket, the first step normally involves waiting for data to arrive on the network. When the packet arrives, it is copied into a buffer within the kernel. The second step is copying this data from the kernel's buffer into our application buffer.

Blocking I/O Model

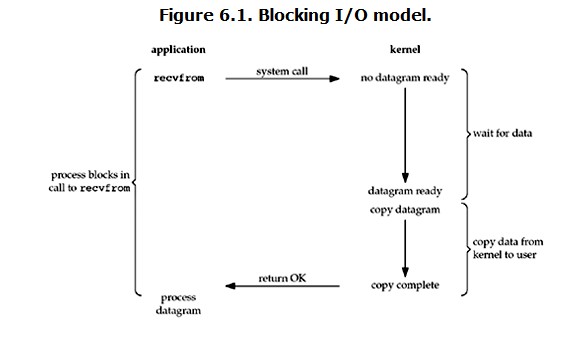

The most prevalent model for I/O is the blocking I/O model , which we have used for all our examples so far in the text. By default, all sockets are blocking. Using a datagram socket for our examples, we have the scenario shown in Figure 6.1 .

Figure 6.1. Blocking I/O model.

We use UDP for this example instead of TCP because with UDP, the concept of data being "ready" to read is simple: either an entire datagram has been received or it has not. With TCP it gets more complicated, as additional variables such as the socket's low-water mark come into play.

In the examples in this section, we also refer to recvfrom as a system call because we are differentiating between our application and the kernel. Regardless of howrecvfrom is implemented (as a system call on a Berkeley-derived kernel or as a function that invokes the getmsg system call on a System V kernel), there is normally a switch from running in the application to running in the kernel, followed at some time later by a return to the application.

In Figure 6.1 , the process calls recvfrom and the system call does not return until the datagram arrives and is copied into our application buffer, or an error occurs. The most common error is the system call being interrupted by a signal, as we described in Section 5.9 . We say that our process is blocked the entire time from when it callsrecvfrom until it returns. When recvfrom returns successfully, our application processes the datagram.

Nonblocking I/O Model

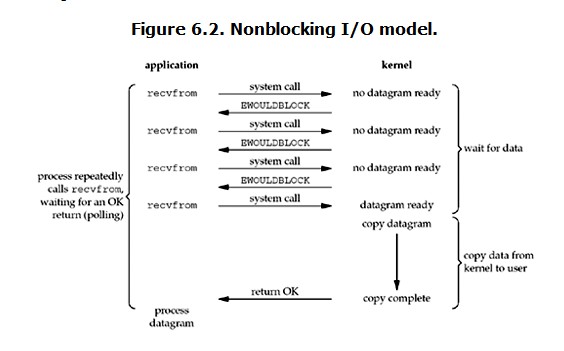

When we set a socket to be nonblocking, we are telling the kernel "when an I/O operation that I request cannot be completed without putting the process to sleep, do not put the process to sleep, but return an error instead." We will describe nonblocking I/O in Chapter 16 , but Figure 6.2 shows a summary of the example we are considering.

Figure 6.2. Nonblocking I/O model.

The first three times that we call recvfrom , there is no data to return, so the kernel immediately returns an error of EWOULDBLOCK instead. The fourth time we callrecvfrom , a datagram is ready, it is copied into our application buffer, and recvfrom returns successfully. We then process the data.

When an application sits in a loop calling recvfrom on a nonblocking descriptor like this, it is called polling . The application is continually polling the kernel to see if some operation is ready. This is often a waste of CPU time, but this model is occasionally encountered, normally on systems dedicated to one function.

I/O Multiplexing Model

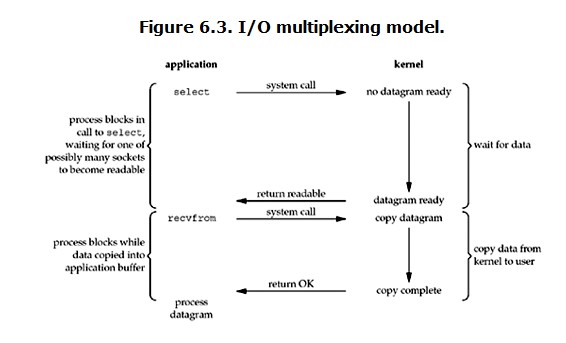

With I/O multiplexing , we call select or poll and block in one of these two system calls, instead of blocking in the actual I/O system call. Figure 6.3 is a summary of the I/O multiplexing model.

Figure 6.3. I/O multiplexing model.

We block in a call to select , waiting for the datagram socket to be readable. When select returns that the socket is readable, we then call recvfrom to copy the datagram into our application buffer.

Comparing Figure 6.3 to Figure 6.1 , there does not appear to be any advantage, and in fact, there is a slight disadvantage because using select requires two system calls instead of one. But the advantage in using select , which we will see later in this chapter, is that we can wait for more than one descriptor to be ready.

Another closely related I/O model is to use multithreading with blocking I/O. That model very closely resembles the model described above, except that instead of usingselect to block on multiple file descriptors, the program uses multiple threads (one per file descriptor), and each thread is then free to call blocking system calls likerecvfrom .

Signal-Driven I/O Model

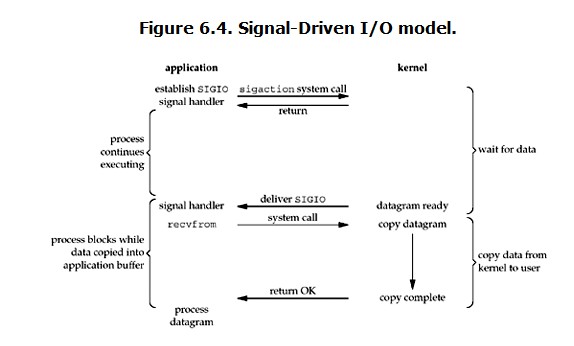

We can also use signals, telling the kernel to notify us with the SIGIO signal when the descriptor is ready. We call this signal-driven I/O and show a summary of it inFigure 6.4 .

Figure 6.4. Signal-Driven I/O model.

We first enable the socket for signal-driven I/O (as we will describe in Section 25.2 ) and install a signal handler using the sigaction system call. The return from this system call is immediate and our process continues; it is not blocked. When the datagram is ready to be read, the SIGIO signal is generated for our process. We can either read the datagram from the signal handler by calling recvfrom and then notify the main loop that the data is ready to be processed (this is what we will do inSection 25.3 ), or we can notify the main loop and let it read the datagram.

Regardless of how we handle the signal, the advantage to this model is that we are not blocked while waiting for the datagram to arrive. The main loop can continue executing and just wait to be notified by the signal handler that either the data is ready to process or the datagram is ready to be read.

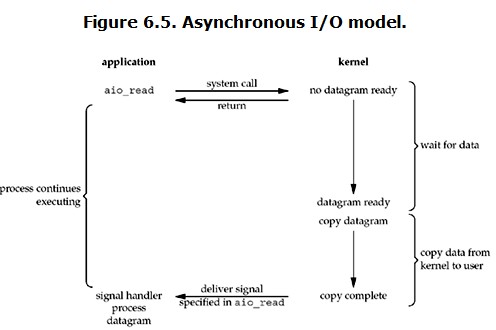

Asynchronous I/O Model

Asynchronous I/O is defined by the POSIX specification, and various differences in the real-time functions that appeared in the various standards which came together to form the current POSIX specification have been reconciled. In general, these functions work by telling the kernel to start the operation and to notify us when the entire operation (including the copy of the data from the kernel to our buffer) is complete. The main difference between this model and the signal-driven I/O model in the previous section is that with signal-driven I/O, the kernel tells us when an I/O operation can be initiated , but with asynchronous I/O, the kernel tells us when an I/O operation is complete . We show an example in Figure 6.5 .

Figure 6.5. Asynchronous I/O model.

We call aio_read (the POSIX asynchronous I/O functions begin with aio_ or lio_ ) and pass the kernel the descriptor, buffer pointer, buffer size (the same three arguments for read ), file offset (similar to lseek ), and how to notify us when the entire operation is complete. This system call returns immediately and our process is not blocked while waiting for the I/O to complete. We assume in this example that we ask the kernel to generate some signal when the operation is complete. This signal is not generated until the data has been copied into our application buffer, which is different from the signal-driven I/O model.

As of this writing, few systems support POSIX asynchronous I/O. We are not certain, for example, if systems will support it for sockets. Our use of it here is as an example to compare against the signal-driven I/O model.

Comparison of the I/O Models

Figure 6.6 is a comparison of the five different I/O models. It shows that the main difference between the first four models is the first phase, as the second phase in the first four models is the same: the process is blocked in a call to recvfrom while the data is copied from the kernel to the caller's buffer. Asynchronous I/O, however, handles both phases and is different from the first four.

Figure 6.6. Comparison of the five I/O models.

Synchronous I/O versus Asynchronous I/O

POSIX defines these two terms as follows:

-

A synchronous I/O operation causes the requesting process to be blocked until that I/O operation completes.

-

An asynchronous I/O operation does not cause the requesting process to be blocked.

Using these definitions, the first four I/O models—blocking, nonblocking, I/O multiplexing, and signal-driven I/O—are all synchronous because the actual I/O operation (recvfrom ) blocks the process. Only the asynchronous I/O model matches the asynchronous I/O definition.

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?