perror的作用:

perror 是 C 语言标准库函数,用于便捷输出系统调用错误信息:

- 头文件:需包含 。

- 原型:void perror(const char *s);,接收一个字符串参数 s。

- 功能:结合全局变量 errno(系统调用失败时会被设置以指示错误类型),先输出传入的字符串 s,再输出冒号、空格,最后输出与当前 errno 对应的系统错误描述。

- 用途:调试时快速定位系统调用类错误(如文件操作失败等),提升调试效率。

进程间通信(IPC)

管道 信号量 共享内存 消息队列 套接字

管道

管道就像一根水管:

- 一端进水(写数据)

- 一端出水(读数据)

- 数据像水一样单向流动

// 可视化理解:进程A → [写端] === 管道 === [读端] → 进程B(进水口) (出水口)

管道的基本特性

关键特点:

- 单向通信:数据只能从一个方向流

- 字节流:没有消息边界,就是一连串字节

- 内核缓冲:内核负责缓存数据

- 父子进程:通常用于有亲缘关系的进程

最简单的管道例子

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main() {

int pipefd[2]; // 管道文件描述符数组

char buf[100];

// 创建管道

if (pipe(pipefd) == -1) {

perror("pipe创建失败");

return 1;

}

printf("管道创建成功!\n");

printf("pipefd[0] = %d (读端)\n", pipefd[0]);

printf("pipefd[1] = %d (写端)\n", pipefd[1]);

// 写入数据到管道

char* message = "Hello Pipe!";

write(pipefd[1], message, strlen(message) + 1); // +1包含\0

printf("写了数据到管道: %s\n", message);

// 从管道读取数据

read(pipefd[0], buf, sizeof(buf));

printf("从管道读到数据: %s\n", buf);

// 关闭管道

close(pipefd[0]);

close(pipefd[1]);

return 0;

}

编译和运行

gcc -o pipe_demo pipe_demo.c

./pipe_demo

输出:

管道创建成功!

pipefd[0] = 3 (读端)

pipefd[1] = 4 (写端)

写了数据到管道: Hello Pipe!

从管道读到数据: Hello Pipe!

关键概念详解

pipe() 函数:

int pipefd[2];

pipe(pipefd);

- 创建两个文件描述符:

- pipefd[0] - 读端(像出水口)

- pipefd[1] - 写端(像进水口)

数据流向:

write(pipefd[1], data) → 管道缓冲区 → read(pipefd[0], buf)

↑ ↑ ↑

写端 内核管理 读端

管道的阻塞特性

重要行为:

// 情况1:管道空时读操作

read(pipefd[0], buf, size); // 会阻塞,直到有数据可读

// 情况2:管道满时写操作

write(pipefd[1], data, size); // 会阻塞,直到有空间可写

// 情况3:所有写端关闭

read(pipefd[0], buf, size); // 返回0 (EOF)

无名管道(只能父子进程)

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

int main() {

int pipefd[2];

char buf[100];

pid_t pid;

// 1. 父进程创建管道

pipe(pipefd);

pid = fork();

if (pid == 0) {

// 子进程:只写不读

close(pipefd[0]); // 关闭读端(不用就关掉)

char* message = "Hello from Child!";

write(pipefd[1], message, strlen(message) + 1);

printf("子进程写了: %s\n", message);

close(pipefd[1]); // 写完关闭写端

exit(0);

} else {

// 父进程:只读不写

close(pipefd[1]); // 关闭写端(不用就关掉)

read(pipefd[0], buf, sizeof(buf));

printf("父进程读到: %s\n", buf);

close(pipefd[0]); // 读完关闭读端

wait(NULL); // 等待子进程结束

}

return 0;

}

有名管道的使用:(任意两个进程间通信)

好的!有名管道(FIFO)来了!这个比无名管道简单直观很多。

有名管道 vs 无名管道

无名管道(刚学的):

// 像电话线:临时连接,挂断就没了

pipe(pipefd); // 内存中创建,没有文件名

// 只能父子进程用

有名管道(现在学的):

最基础的有名管道使用

// 像邮箱:有地址,谁都可以往里投信

mkfifo("/tmp/myfifo", 0666); // 文件系统中创建真实文件

// 任意进程都能用

步骤1:创建FIFO文件

#include <stdio.h>

#include <sys/stat.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

// 创建有名管道(像创建文件一样)

if (mkfifo("/tmp/myfifo", 0666) == -1) {

perror("mkfifo");

return 1;

}

printf("有名管道创建成功:/tmp/myfifo\n");

return 0;

}

编译运行:

gcc -o create_fifo create_fifo.c

./create_fifo

ls -l /tmp/myfifo # 看到:prw-r--r-- 开头的p表示管道文件

实际通信例子:两个独立进程

进程A:写数据

// writer.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <string.h>

int main() {

int fd;

char* message = "Hello FIFO!";

// 打开FIFO文件(会阻塞,直到有进程来读)

printf("写进程等待读进程连接...\n");

fd = open("/tmp/myfifo", O_WRONLY);

// 写入数据

write(fd, message, strlen(message) + 1);

printf("写进程发送: %s\n", message);

close(fd);

return 0;

}

进程B:读数据

// reader.c

#include <stdio.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

int fd;

char buf[100];

// 打开FIFO文件(会阻塞,直到有进程来写)

printf("读进程等待写进程连接...\n");

fd = open("/tmp/myfifo", O_RDONLY);

// 读取数据

read(fd, buf, sizeof(buf));

printf("读进程收到: %s\n", buf);

close(fd);

return 0;

}

测试方法

开两个终端窗口:

终端1(读进程):

gcc -o reader reader.c

./reader

# 输出:读进程等待写进程连接... (会卡在这里)

终端2(写进程):

gcc -o writer writer.c

./writer

# 输出:写进程等待读进程连接...

# 写进程发送: Hello FIFO!

然后终端1自动显示:

读进程收到: Hello FIFO!

有名管道的阻塞特性

关键行为:

// 情况1:只有读进程

open("/tmp/myfifo", O_RDONLY); // 阻塞,等写进程

// 情况2:只有写进程

open("/tmp/myfifo", O_WRONLY); // 阻塞,等读进程

// 情况3:读写进程都到位 → 同时继续执行

有名管道的实际应用场景

场景1:Shell命令使用FIFO

# 终端1:创建FIFO并读取

mkfifo /tmp/myfifo

cat /tmp/myfifo

# 终端2:写入数据

echo "Hello" > /tmp/myfifo

# 终端1立即显示:Hello

场景2:多个写进程,一个读进程

// 多个进程都可以往同一个FIFO写数据

// 读进程会收到所有数据

清理FIFO文件

// 程序结束时删除FIFO文件

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main() {

// 使用FIFO...

// 最后删除

unlink("/tmp/myfifo");

printf("FIFO文件已删除\n");

return 0;

}

或者手动删除:

rm /tmp/myfifo

有名管道的核心思想:

- 先建"邮箱":mkfifo 创建管道文件

- 写信投递:写进程 open + write

- 收信阅读:读进程 open + read

- 双方配合:缺一方就阻塞等待

比无名管道简单的地方:

- 不用操心文件描述符继承

- 不用关系进程亲缘

- 像普通文件一样操作

管道的使用规则

规则1:及时关闭不用的端

// 如果只读不写,就关闭写端 close(pipefd[1]);

// 如果只写不读,就关闭读端 close(pipefd[0]);

规则2:理解数据流

父进程 → 子进程:

父: close(pipefd[0]); write(pipefd[1]);

子: close(pipefd[1]); read(pipefd[0]);

子进程 → 父进程:

子: close(pipefd[0]); write(pipefd[1]);

父: close(pipefd[1]); read(pipefd[0]);

常见问题解答

Q: 为什么要在父子进程中都关闭不用的端?

A: 因为文件描述符会被继承,如果不关闭:

- 读进程不关闭写端 → 永远读不到EOF

- 写进程不关闭读端 → 浪费资源

Q: 管道能双向通信吗?

A: 不能!需要双向通信就创建两个管道:

int pipe1[2], pipe2[2];

pipe(pipe1); // 父→子

pipe(pipe2); // 子→父

管道核心概念总结:

- pipe(pipefd) 创建一进一出两个口

- pipefd[0] 读,pipefd[1] 写

- 数据单向流动,像水管

- 主要用于父子进程通信

- 记得关闭不用的端口

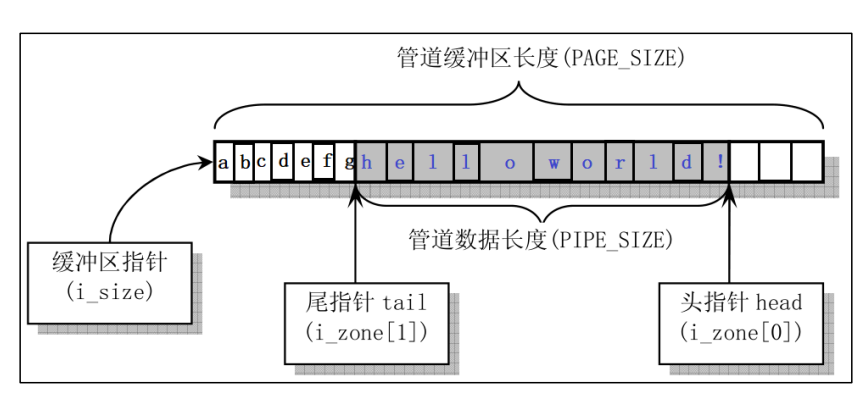

管道的底层实现:

// 内核源码中的结构(简化版):

struct pipe_inode_info {

struct pipe_buffer *bufs; // 缓冲区数组

unsigned int head; // 读位置

unsigned int tail; // 写位置

unsigned int readers; // 读进程数

unsigned int writers; // 写进程数

wait_queue_head_t wait; // 等待队列

};

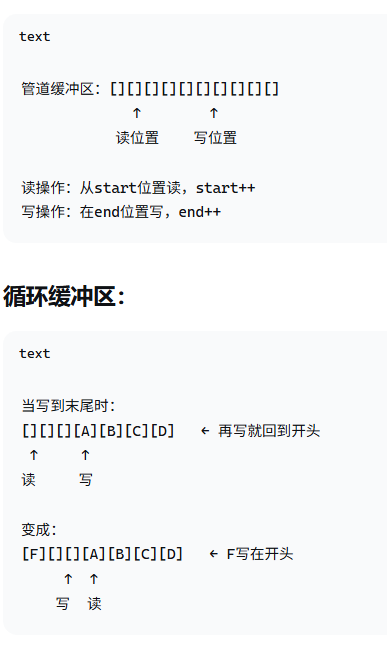

- 环形缓冲区:在内核空间的内存区域

- 两个指针:读指针和写指针

- 等待队列:管理阻塞的进程

- 文件抽象:通过文件描述符访问

- 同步机制:自动处理读写同步

管道最多是半双工(还要创俩管道)

1315

1315

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?