Microservices

a definition of this new architectural term

The term “Microservice Architecture” has sprung up over the last few

years to describe a particular way of designing software applications

as suites of independently deployable services. While there is no

precise definition of this architectural style, there are certain

common characteristics around organization around business capability,

automated deployment, intelligence in the endpoints, and decentralized

control of languages and data.25 March 2014

微服务

有关这个新的技术架构术语的定义:

“微服务体系结构”这一术语在过去几年中如雨后春笋般涌现,用来描述将软件应用程序设计为可独立部署的服务套件的特定方式。虽然对这种架构风格没有准确的定义,但围绕业务功能、自动化部署、终端的智能以及语言和数据的分散控制,组织中存在某些共同的特征。

2014年3月25日

James Lewis

James Lewis

James Lewis is a Principal Consultant at Thoughtworks and member of the Technology Advisory Board. James’ interest in building applications out of small collaborating services stems from a background in integrating enterprise systems at scale. He’s built a number of systems using microservices and has been an active participant in the growing community for a couple of years.

詹姆斯·刘易斯是Thoughtworks的首席顾问和技术咨询委员会成员。James对从小型协作服务构建应用程序的兴趣源于大规模集成企业系统的背景。他使用微服务构建了许多系统,几年来一直是不断增长的社区的积极参与者。

Martin Fowler is an author, speaker, and general loud-mouth on software development. He’s long been puzzled by the problem of how to componentize software systems, having heard more vague claims than he’s happy with. He hopes that microservices will live up to the early promise its advocates have found.

Martin Fowler是一位作家、演说家,也是软件开发领域的大腕。长期以来,他一直被如何将软件系统组件化的问题所困扰,因为他听到了比他满意的更多模糊的说法。他希望微服务能兑现其倡导者早期的承诺。

“Microservices” - yet another new term on the crowded streets of software architecture. Although our natural inclination is to pass such things by with a contemptuous glance, this bit of terminology describes a style of software systems that we are finding more and more appealing. We’ve seen many projects use this style in the last few years, and results so far have been positive, so much so that for many of our colleagues this is becoming the default style for building enterprise applications. Sadly, however, there’s not much information that outlines what the microservice style is and how to do it.

“微服务”——这是在软件架构这条熙熙攘攘的大街上出现的又一个新词儿。我们自然会对它投过轻蔑的一瞥,但是这个小小的术语却描述了一种引人入胜的软件系统的风格。最近几年,我们已经看到许多项目使用了这种风格,而且至今其结果都是良好的,以至于对于我们许多ThoughtWorks的同事来说,它正在成为构建企业应用系统的缺省的风格。然而,很不幸的是,我们找不到有关它的概要信息,即什么是微服务风格,以及如何设计微服务风格的架构。

In short, the microservice architectural style [1] is an approach to developing a single application as a suite of small services, each running in its own process and communicating with lightweight mechanisms, often an HTTP resource API. These services are built around business capabilities and independently deployable by fully automated deployment machinery. There is a bare minimum of centralized management of these services, which may be written in different programming languages and use different data storage technologies.

简而言之,微服务架构风格[1]这种开发方法,是以开发一组小型服务的方式来开发一个独立的应用系统的。其中每个小型服务都运行在自己的进程中,并经常采用HTTP资源API这样轻量的机制来相互通信。这些服务围绕业务功能进行构建,并能通过全自动的部署机制来进行独立部署。这些微服务可以使用不同的语言来编写,并且可以使用不同的数据存储技术。对这些微服务我们仅做最低限度的集中管理。

My Microservices Resource Guide provides links to the best articles, videos, books, and podcasts about microservices.

在我的“微服务资源指南”中能找到有关微服务最好的文章、视频、图书和播客媒体。

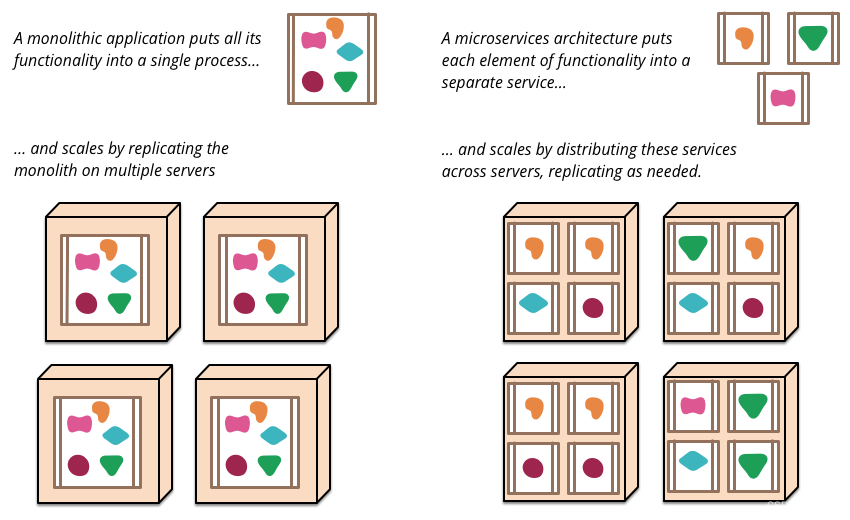

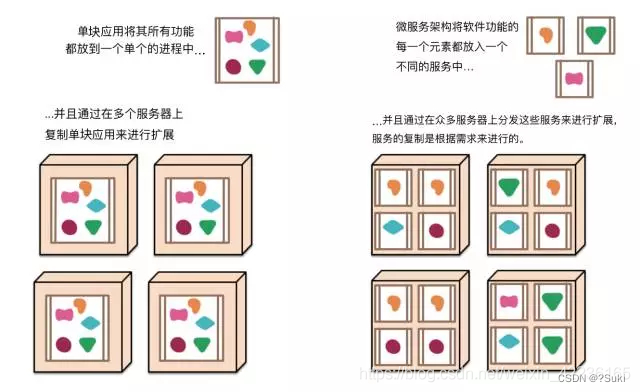

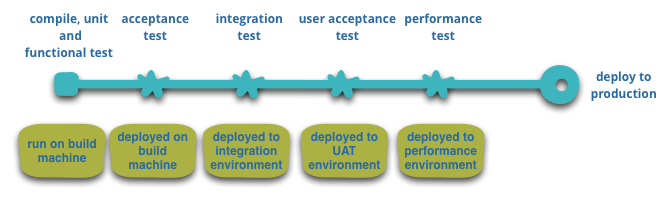

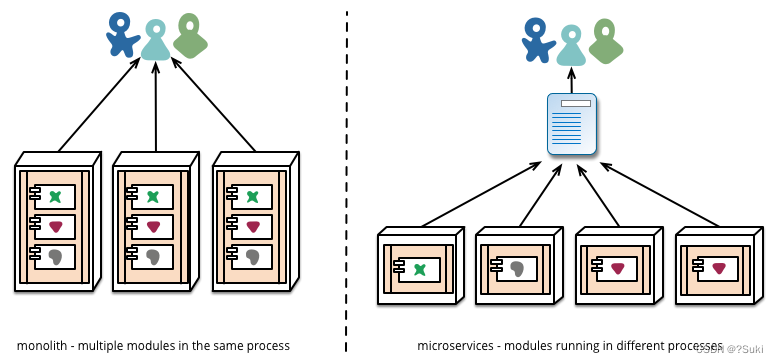

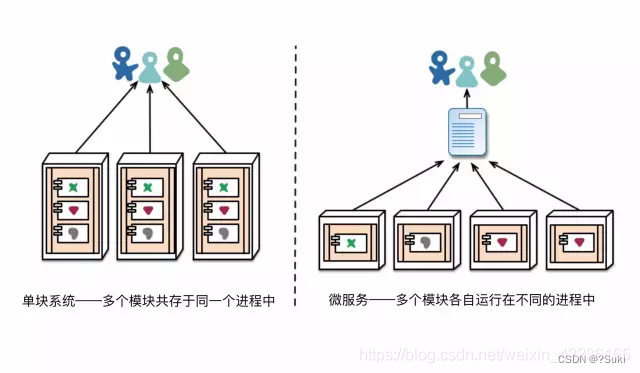

To start explaining the microservice style it’s useful to compare it to the monolithic style: a monolithic application built as a single unit. Enterprise Applications are often built in three main parts: a client-side user interface (consisting of HTML pages and javascript running in a browser on the user’s machine) a database (consisting of many tables inserted into a common, and usually relational, database management system), and a server-side application. The server-side application will handle HTTP requests, execute domain logic, retrieve and update data from the database, and select and populate HTML views to be sent to the browser. This server-side application is a monolith - a single logical executable[2]. Any changes to the system involve building and deploying a new version of the server-side application.

要开始解释微服务风格,将其与整体式风格进行比较是很有用的:作为单个单元构建的整体式应用程序。企业应用程序通常由三个主要部分构建: 客户端用户界面(由 HTML 页面和在用户计算机上的浏览器中运行的 javascript 组成) 数据库(由插入到公共且通常是关系数据库管理中的许多表组成)系统)和服务器端应用程序。服务器端应用程序将处理 HTTP 请求、执行域逻辑、从数据库中检索和更新数据,以及选择和填充要发送到浏览器的 HTML 视图。这个服务器端应用程序是一个整体——一个单一的逻辑可执行文件[2]。对系统的任何更改都涉及构建和部署新版本的服务器端应用程序。

Such a monolithic server is a natural way to approach building such a system. All your logic for handling a request runs in a single process, allowing you to use the basic features of your language to divide up the application into classes, functions, and namespaces. With some care, you can run and test the application on a developer’s laptop, and use a deployment pipeline to ensure that changes are properly tested and deployed into production. You can horizontally scale the monolith by running many instances behind a load-balancer.

这样的单块服务器是构建上述系统的一种自然的方式。处理用户请求的所有逻辑都运行在一个单个的进程内,从而能使用编程语言的基本特性,来把应用系统划分为类、函数和命名空间。通过精心设计,就能在开发人员的笔记本电脑上运行和测试这样的应用系统,并且使用一个部署流水线来确保变更被很好地进行了测试,并被部署到生产环境中。通过负载均衡器运行许多实例,来将这个单块应用进行横向扩展。

Monolithic applications can be successful, but increasingly people are feeling frustrations with them - especially as more applications are being deployed to the cloud . Change cycles are tied together - a change made to a small part of the application, requires the entire monolith to be rebuilt and deployed. Over time it’s often hard to keep a good modular structure, making it harder to keep changes that ought to only affect one module within that module. Scaling requires scaling of the entire application rather than parts of it that require greater resource.

单块应用系统可以被成功地实现,但是渐渐地,特别是随着越来越多的应用系统正被部署到云端,人们对它们开始表现出不满。软件变更受到了很大的限制,应用系统的一个很小的部分的一处变更,也需要将整个单块应用系统进行重新构建和部署。随着时间的推移,单块应用开始变得经常难以保持一个良好的模块化结构,这使得它变得越来越难以将一个模块的变更的影响控制在该模块内。当对系统进行扩展时,不得不扩展整个应用系统,而不能仅扩展该系统中需要更多资源的那些部分。

Figure 1: Monoliths and Microservices

图1: 单块应用和微服务

These frustrations have led to the microservice architectural style: building applications as suites of services. As well as the fact that services are independently deployable and scalable, each service also provides a firm module boundary, even allowing for different services to be written in different programming languages. They can also be managed by different teams .

这些不满导致了微服务架构风格的诞生:以构建一组小型服务的方式来构建应用系统。除了这些服务能被独立地部署和扩展,每一个服务还能提供一个稳固的模块边界,甚至能允许使用不同的编程语言来编写不同的服务。这些服务也能被不同的团队来管理。

We do not claim that the microservice style is novel or innovative, its roots go back at least to the design principles of Unix. But we do think that not enough people consider a microservice architecture and that many software developments would be better off if they used it.

我们并不认为微服务风格是一个新颖或创新的概念,它的起源至少可以追溯到Unix的设计原则。但是我们觉得,考虑微服务架构的人还不够多,并且如果对其加以使用,许多软件的开发工作能变得更好。

[1]2011年5月在威尼斯附近的一个软件架构工作坊中,大家开始讨论“微服务”这个术语,因为这个词可以描述参会者们在架构领域进行探索时所见到的一种通用的架构风格。2012年5月,这群参会者决定将“微服务”作为描述这种架构风格的最贴切的名字。在2012年3月波兰的克拉科夫市举办的“33rd Degree”技术大会上,本文作者之一James在其“Microservices - Java, the Unix Way”演讲中以案例的形式谈到了这些微服务的观点,与此同时,Fred George也表达了同样的观点。Netflix公司的Adrian Cockcroft将这种方法描述为“细粒度的SOA”,并且作为先行者和本文下面所提到的众人已经着手在Web领域进行了实践——Joe Walnes, Dan North, Evan Botcher 和 Graham Tackley。

[2]“单块”(monolith)这个术语已经被Unix社区使用一段时间了。它出现在The Art of Unix Programming一书中,来描述那些变得庞大的系统。

目录

- CONTENTS

- 1 Characteristics of a Microservice Architecture--微服务体系结构的特点

- 1.1 Componentization via Services--“组件化”与“多服务”

- 1.2 Organized around Business Capabilities--围绕“业务功能”组织团队

- SIDEBARS--How big is a microservice? -- 一个微服务应该有多大?

- 1.3 Products not Projects--“做产品”而不是“做项目”

- 1.4 Smart endpoints and dumb pipes--“智能端点”与“傻瓜管道”

- SIDEBARS--Microservices and SOA -- 微服务与SOA

- 1.5 Decentralized Governance--“去中心化”地治理技术

- SIDEBARS--Many languages, many options--多种编程语言,多种选择可能

- 1.6 Decentralized Data Management--“去中心化”地管理数据

- SIDEBARS--Battle-tested standards and enforced standards--“实战检验”的标准与“强制执行”的标准

- 1.7 Infrastructure Automation--“基础设施”自动化

- SIDEBARS--Make it easy to do the right thing--让“方向正确地做事”更容易

- 1.8 Design for failure--“容错”设计

- SIDEBARS--The circuit breaker and production ready code--"断路器"与“可随时上线的代码”

- SIDEBARS--Synchronous calls considered harmful--“同步调用”有害

- 1.9 Evolutionary Design--“演进式”设计

- 2 Are Microservices the Future? --未来的方向是“微服务”吗?

- 3 References--参考资料

CONTENTS

1 Characteristics of a Microservice Architecture–微服务体系结构的特点

We cannot say there is a formal definition of the microservices architectural style, but we can attempt to describe what we see as common characteristics for architectures that fit the label. As with any definition that outlines common characteristics, not all microservice architectures have all the characteristics, but we do expect that most microservice architectures exhibit most characteristics. While we authors have been active members of this rather loose community, our intention is to attempt a description of what we see in our own work and in similar efforts by teams we know of. In particular we are not laying down some definition to conform to.

虽然不能说存在微服务架构风格的正式定义,但是可以尝试描述我们所见到的能够被贴上微服务标签的那些架构的共性。下面所描述的所有这些共性,并不是所有的微服务架构都完全具备,但是我们确实期望大多数微服务架构都具备这些共性中的大多数特性。尽管我们两位作者已经成为这个相当松散的社区的活跃成员,但我们的本意还是试图描述我们两人在自己和自己所了解的团队的工作中所看到的情况。特别要指出,我们不会制定大家需要遵循的微服务的定义。

1.1 Componentization via Services–“组件化”与“多服务”

For as long as we’ve been involved in the software industry, there’s been a desire to build systems by plugging together components, much in the way we see things are made in the physical world. During the last couple of decades we’ve seen considerable progress with large compendiums of common libraries that are part of most language platforms.

自我们开始从事软件业已来,发现大家都有一个把组件插在一起来构建系统的愿望,就像在物理世界中所看到的那样。在过去几十年中,我们已经看到,在公共软件库方面已经取得了相当大的进展,这些软件库是大多数编程语言平台的组成部分。

When talking about components we run into the difficult definition of what makes a component. Our definition is that a component is a unit of software that is independently replaceable and upgradeable.

当谈到组件时,就会碰到一个有关定义的难题,即什么是组件?我们的定义是,一个组件就是一个可以独立更换和升级的软件单元。

Microservice architectures will use libraries, but their primary way of componentizing their own software is by breaking down into services. We define libraries as components that are linked into a program and called using in-memory function calls, while services are out-of-process components who communicate with a mechanism such as a web service request, or remote procedure call. (This is a different concept to that of a service object in many OO programs [3].)

微服务架构也会使用软件库,但其将自身软件进行组件化的主要方法是将软件分解为诸多服务。我们将软件库(libraries)定义为这样的组件,即它能被链接到一段程序,且能通过内存中的函数来进行调用。然而,服务(services)是进程外的组件,它们通过诸如web service请求或远程过程调用这样的机制来进行通信(这不同于许多面向对象的程序中的service object概念[3])。

One main reason for using services as components (rather than libraries) is that services are independently deployable. If you have an application [4] that consists of a multiple libraries in a single process, a change to any single component results in having to redeploy the entire application. But if that application is decomposed into multiple services, you can expect many single service changes to only require that service to be redeployed. That’s not an absolute, some changes will change service interfaces resulting in some coordination, but the aim of a good microservice architecture is to minimize these through cohesive service boundaries and evolution mechanisms in the service contracts.

以使用服务(而不是以软件库)的方式来实现组件化的一个主要原因是,服务可被独立部署。如果一个应用系统[4]由在单个进程中的多个软件库所组成,那么对任一组件做一处修改,都不得不重新部署整个应用系统。但是如果该应用系统被分解为多个服务,那么对于一个服务的多处修改,仅需要重新部署这一个服务。当然这也不是绝对的,一些变更服务接口的修改会导致多个服务之间的协同修改。但是一个良好的微服务架构的目的,是通过内聚的服务边界和服务协议方面的演进机制,来将这样的修改变得最小化。

Another consequence of using services as components is a more explicit component interface. Most languages do not have a good mechanism for defining an explicit Published Interface. Often it’s only documentation and discipline that prevents clients breaking a component’s encapsulation, leading to overly-tight coupling between components. Services make it easier to avoid this by using explicit remote call mechanisms.

以服务的方式来实现组件化的另一个结果,是能获得更加显式的(explicit)组件接口。大多数编程语言并没有一个良好的机制来定义显式的发布接口(Published Interface)。通常情况下,这样的接口仅仅是文档声明和团队纪律,来避免客户端破坏组件的封装,从而导致组件间出现过度紧密的耦合。通过使用显式的远程调用机制,服务能更容易地避免这种情况发生。

Using services like this does have downsides. Remote calls are more expensive than in-process calls, and thus remote APIs need to be coarser-grained, which is often more awkward to use. If you need to change the allocation of responsibilities between components, such movements of behavior are harder to do when you’re crossing process boundaries.

如此这般地使用服务,也会有不足之处。比起进程内调用,远程调用更加昂贵。所以远程调用API接口必须是粗粒度的,而这往往更加难以使用。如果需要修改组件间的职责分配,那么当跨越进程边界时,这种组件行为的改动会更加难以实现。

At a first approximation, we can observe that services map to runtime processes, but that is only a first approximation. A service may consist of multiple processes that will always be developed and deployed together, such as an application process and a database that’s only used by that service.

近似地,我们可以把一个个服务映射为一个个运行时的进程,但这仅仅是一个近似。一个服务可能包括总是在一起被开发和部署的多个进程,比如一个应用系统的进程和仅被该服务使用的数据库。

[3]许多面向对象的设计者,包括我们自己,都使用领域驱动设计中service object这个术语,来描述那种执行一段未被绑定到一个entity对象上的重要的逻辑过程的对象。这不同于本文所讨论的"service"的概念。可悲的是,service这个术语同时具有这两个含义,我们必须忍受这样的多义词。

[4]我们认为一个应用系统是一个社会性的构建单元,来将一个代码库、功能组和资金体(body of funding)结合起来。

1.2 Organized around Business Capabilities–围绕“业务功能”组织团队

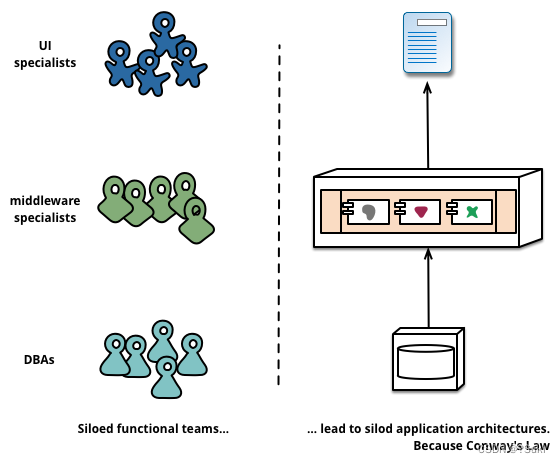

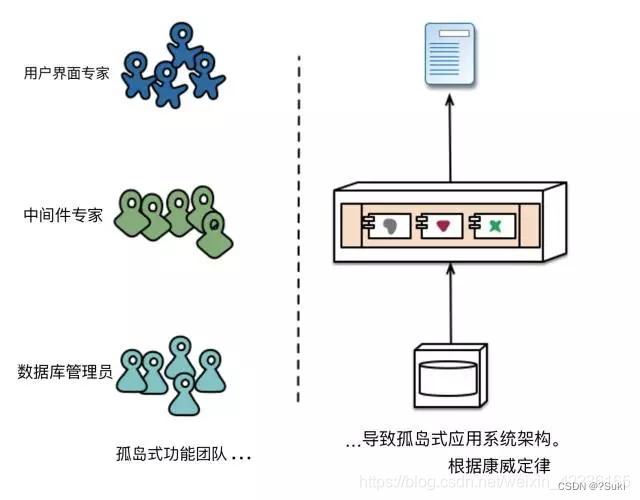

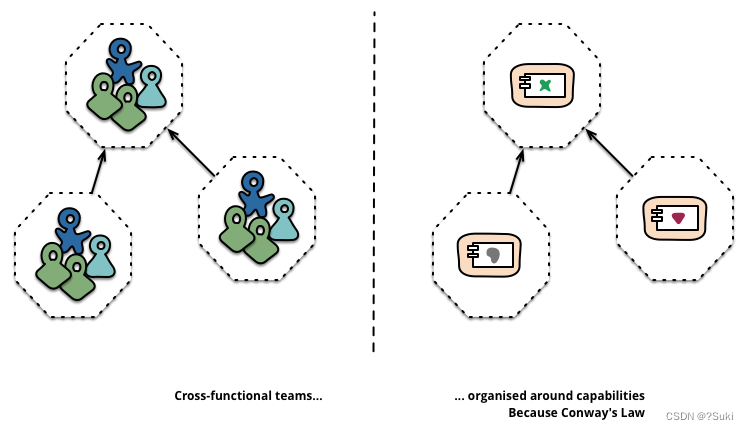

When looking to split a large application into parts, often management focuses on the technology layer, leading to UI teams, server-side logic teams, and database teams. When teams are separated along these lines, even simple changes can lead to a cross-team project taking time and budgetary approval. A smart team will optimise around this and plump for the lesser of two evils - just force the logic into whichever application they have access to. Logic everywhere in other words. This is an example of Conway’s Law in action.

当在寻求将一个大型应用系统分解成几部分时,公司管理层往往会聚焦在技术层面上,这会导致组建用户界面团队、服务器端团队和数据库团队。当团队沿着这些技术线分开后,即使要实现软件一个简单的变更,也会导致跨团队的项目时延和预算审批。在这种情况下,聪明的团队会进行局部优化,“两害相权取其轻”,来直接把代码逻辑塞到他们能访问到的任意应用系统中。换句话说,这种情况会导致代码逻辑散布在系统各处。这就是康威定律[5]在起作用的活生生的例子。

Any organization that designs a system (defined broadly) will produce a design whose structure is a copy of the organization’s communication structure.

– Melvin Conway, 1968

任何设计(广义上的)系统的组织,都会产生这样一个设计,即该设计的结构与该组织的沟通结构相一致。

——梅尔文•康威(Melvyn Conway), 1967年

Figure 2: Conway’s Law in action

The microservice approach to division is different, splitting up into services organized around business capability. Such services take a broad-stack implementation of software for that business area, including user-interface, persistant storage, and any external collaborations. Consequently the teams are cross-functional, including the full range of skills required for the development: user-experience, database, and project management.

微服务使用不同的方法来分解系统,即根据业务功能(business capability)来将系统分解为若干服务。这些服务针对该业务领域提供多层次广泛的软件实现,包括用户界面、持久性存储以及任何对外的协作性操作。因此,团队是跨职能的,它拥有软件开发所需的全方位的技能:用户体验、数据库和项目管理。

Figure 3: Service boundaries reinforced by team boundaries

Figure 3: Service boundaries reinforced by team boundaries

How big is a microservice?

Although “microservice” has become a popular name for this architectural style, its name does lead to an unfortunate focus on the size of service, and arguments about what constitutes “micro”. In our conversations with microservice practitioners, we see a range of sizes of services. The largest sizes reported follow Amazon’s notion of the Two Pizza Team (i.e. the whole team can be fed by two pizzas), meaning no more than a dozen people. On the smaller size scale we’ve seen setups where a team of half-a-dozen would support half-a-dozen services.

SIDEBARS–How big is a microservice? – 一个微服务应该有多大?

一个微服务应该有多大?

尽管对于这种架构风格,“微服务”已经成为一个流行的名字,但是这个名字确实会不幸地导致大家对服务规模的关注,并且产生了有关什么是“微”的争论。在与微服务从业者的交谈中,我们看到了有关服务的一系列规模。所听到的最大的一个服务的规模,是遵循了亚马逊的“两个比萨团队”(即一个团队可以被两个比萨所喂饱)的理念,这意味着这个团队不会多于12人。对于规模较小的服务,我们已经看到一个6人的团队在支持6个服务。

This leads to the question of whether there are sufficiently large differences within this size range that the service-per-dozen-people and service-per-person sizes shouldn’t be lumped under one microservices label. At the moment we think it’s better to group them together, but it’s certainly possible that we’ll change our mind as we explore this style further.

这引出了一个问题,即“每12人做一个服务”和“每人做一个服务”这样有关服务规模的差距,是否已经大到不能将两者都纳入微服务之下?此时,我们认为最好还是把它们归为一类,但是随着进一步探索这种架构风格,绝对有可能我们将来会改变主意。

One company organised in this way is www.comparethemarket.com. Cross functional teams are responsible for building and operating each product and each product is split out into a number of individual services communicating via a message bus.

以上述方式来组织团队的公司是www.comparethemarket.com。跨职能团队负责构建和运维每个产品,而每个产品被拆分为多个独立的服务,彼此通过一个消息总线来通信。

Large monolithic applications can always be modularized around business capabilities too, although that’s not the common case. Certainly we would urge a large team building a monolithic application to divide itself along business lines. The main issue we have seen here, is that they tend to be organised around too many contexts. If the monolith spans many of these modular boundaries it can be difficult for individual members of a team to fit them into their short-term memory. Additionally we see that the modular lines require a great deal of discipline to enforce. The necessarily more explicit separation required by service components makes it easier to keep the team boundaries clear.

大型单块应用系统也可以始终根据业务功能来进行模块化设计,虽然这并不常见。当然,我们会敦促构建单块应用系统的大型团队根据业务线来将自己分解为若干小团队。在这方面,我们已经看到的主要问题是,他们往往是一个团队包含了太多的业务功能。如果这个“单块”跨越了许多模块的边界,那么这个团队的每一个成员都难以记忆所有这些模块的业务功能。此外,我们看到这些模块的边界需要大量的团队纪律性来强制维持。而实现组件化的服务所必要的更加显式的边界,能更加容易地保持团队边界的清晰性。

[5]原始论文参见梅尔文•康威的网站

1.3 Products not Projects–“做产品”而不是“做项目”

Most application development efforts that we see use a project model: where the aim is to deliver some piece of software which is then considered to be completed. On completion the software is handed over to a maintenance organization and the project team that built it is disbanded.

我们所看的的大部分应用系统的开发工作都使用项目模型:目标是交付某一块软件,之后就认为完工了。一旦完工后,软件就被移交给维护团队,接着那个构建该软件的项目团队就会被解散。

Microservice proponents tend to avoid this model, preferring instead the notion that a team should own a product over its full lifetime. A common inspiration for this is Amazon’s notion of “you build, you run it” where a development team takes full responsibility for the software in production. This brings developers into day-to-day contact with how their software behaves in production and increases contact with their users, as they have to take on at least some of the support burden.

微服务的支持者们倾向于避免使用上述模型,而宁愿采纳“一个团队在一个产品的整个生命周期中都应该保持对其拥有”这样的理念。通常认为这一点源自亚马逊的“谁构建,谁运行”的理念,即一个开发团队对一个在生产环境下运行的软件负全责。这会使开发人员每天都会关注软件是如何在生产环境下运行的,并且增进他们与用户的联系,因为他们必须承担某些支持工作。

The product mentality, ties in with the linkage to business capabilities. Rather than looking at the software as a set of functionality to be completed, there is an on-going relationship where the question is how can software assist its users to enhance the business capability.

这样的“产品”理念,是与业务功能的联动绑定在一起的。它不会将软件看作是一个待完成的功能集合,而是认为存在这样一个持续的关系,即软件如何能助其客户来持续增进业务功能。

There’s no reason why this same approach can’t be taken with monolithic applications, but the smaller granularity of services can make it easier to create the personal relationships between service developers and their users.

当然,单块应用系统的开发工作也可以遵循上述“产品”理念,但是更细粒度的服务,能让服务的开发者与其用户之间的个人关系的创建变得更加容易。

1.4 Smart endpoints and dumb pipes–“智能端点”与“傻瓜管道”

When building communication structures between different processes, we’ve seen many products and approaches that stress putting significant smarts into the communication mechanism itself. A good example of this is the Enterprise Service Bus (ESB), where ESB products often include sophisticated facilities for message routing, choreography, transformation, and applying business rules.

当在不同的进程之间构建各种通信结构时,我们已经看到许多产品和方法,来强调将大量的智能特性纳入通信机制本身。这种状况的一个典型例子,就是“企业服务总线”(Enterprise Service Bus, ESB)。ESB产品经常包括高度智能的设施,来进行消息的路由、编制(choreography)、转换,并应用业务规则。

SIDEBARS–Microservices and SOA – 微服务与SOA

When we’ve talked about microservices a common question is whether this is just Service Oriented Architecture (SOA) that we saw a decade ago. There is merit to this point, because the microservice style is very similar to what some advocates of SOA have been in favor of. The problem, however, is that SOA means too many different things, and that most of the time that we come across something called “SOA” it’s significantly different to the style we’re describing here, usually due to a focus on ESBs used to integrate monolithic applications.

当我们谈论微服务时,一个常见的问题是这是否只是我们十年前看到的面向服务的架构 (SOA)。这一点是有道理的,因为微服务风格与一些 SOA 拥护者所支持的风格非常相似。然而,问题是 SOA 意味着太多不同的东西,而且大多数时候我们遇到的东西叫做“SOA”,它与我们在这里描述的风格有很大不同,通常是因为关注的是 ESB集成单体应用程序。

In particular we have seen so many botched implementations of service orientation - from the tendency to hide complexity away in ESB’s [5], to failed multi-year initiatives that cost millions and deliver no value, to centralised governance models that actively inhibit change, that it is sometimes difficult to see past these problems.

特别是,我们看到了如此多的面向服务的拙劣实现——从 ESB [5] 中隐藏复杂性的趋势,到花费数百万美元且没有提供任何价值的失败的多年计划,再到积极抑制变化的集中式治理模型,这有时很难看清这些问题。

Certainly, many of the techniques in use in the microservice community have grown from the experiences of developers integrating services in large organisations. The Tolerant Reader pattern is an example of this. Efforts to use the web have contributed, using simple protocols is another approach derived from these experiences - a reaction away from central standards that have reached a complexity that is, frankly, breathtaking. (Any time you need an ontology to manage your ontologies you know you are in deep trouble.)

当然,微服务社区中使用的许多技术都源于开发人员在大型组织中集成服务的经验。 Tolerant Reader 模式就是一个例子。使用网络的努力做出了贡献,使用简单的协议是从这些经验中衍生出来的另一种方法 - 对已经达到复杂程度的中央标准的反应,坦率地说,令人叹为观止。 (任何时候你需要一个本体来管理你的本体,你就知道你有大麻烦了。)

This common manifestation of SOA has led some microservice advocates to reject the SOA label entirely, although others consider microservices to be one form of SOA [6], perhaps service orientation done right. Either way, the fact that SOA means such different things means it’s valuable to have a term that more crisply defines this architectural style.

SOA 的这种常见表现导致一些微服务拥护者完全拒绝 SOA 标签,尽管其他人认为微服务是 SOA [6] 的一种形式,也许面向服务是正确的。无论哪种方式,SOA 意味着如此不同的东西这一事实意味着拥有一个更清晰地定义这种架构风格的术语是有价值的。

The microservice community favours an alternative approach: smart endpoints and dumb pipes. Applications built from microservices aim to be as decoupled and as cohesive as possible - they own their own domain logic and act more as filters in the classical Unix sense - receiving a request, applying logic as appropriate and producing a response. These are choreographed using simple RESTish protocols rather than complex protocols such as WS-Choreography or BPEL or orchestration by a central tool.

微服务社区主张采用另一种做法:智能端点(smart endpoints)和傻瓜管道(dumb pipes)。使用微服务所构建的各个应用的目标,都是尽可能地实现“高内聚和低耦合”——他们拥有自己的领域逻辑,并且更多地是像经典Unix的“过滤器”(filter)那样来工作——即接收一个请求,酌情对其应用业务逻辑,并产生一个响应。这些应用通过使用一些简单的REST风格的协议来进行编制,而不去使用诸如下面这些复杂的协议,即"WS-编制"(WS-Choreography)、BPEL或通过位于中心的工具来进行编排(orchestration)。

The two protocols used most commonly are HTTP request-response with resource API’s and lightweight messaging[7]. The best expression of the first is

Be of the web, not behind the web

– Ian Robinson

微服务最常用的两种协议是:带有资源API的HTTP“请求-响应”协议,和轻量级的消息发送协议[6]。对于前一种协议的最佳表述是:

成为Web,而不是躲着Web (Be of the web, not behind the web)——Ian Robinson

Microservice teams use the principles and protocols that the world wide web (and to a large extent, Unix) is built on. Often used resources can be cached with very little effort on the part of developers or operations folk.

这些微服务团队在开发中,使用在构建万维网(world wide web)时所使用的原则和协议(并且在很大程度上,这些原则和协议也是在构建Unix系统时所使用的)。那些被使用过的HTTP资源,通常能被开发或运维人员轻易地缓存起来。

The second approach in common use is messaging over a lightweight message bus. The infrastructure chosen is typically dumb (dumb as in acts as a message router only) - simple implementations such as RabbitMQ or ZeroMQ don’t do much more than provide a reliable asynchronous fabric - the smarts still live in the end points that are producing and consuming messages; in the services.

最常用的第二种协议,是通过一个轻量级的消息总线来进行消息发送。此时所选择的基础设施,通常是“傻瓜”(dumb)型的(仅仅像消息路由器所做的事情那样傻瓜)——像RabbitMQ或ZeroMQ那样的简单实现,即除了提供可靠的异步机制(fabric)以外不做其他任何事情——智能功能存在于那些生产和消费诸多消息的各个端点中,即存在于各个服务中。

In a monolith, the components are executing in-process and communication between them is via either method invocation or function call. The biggest issue in changing a monolith into microservices lies in changing the communication pattern. A naive conversion from in-memory method calls to RPC leads to chatty communications which don’t perform well. Instead you need to replace the fine-grained communication with a coarser -grained approach.

在一个单块系统中,各个组件在同一个进程中运行。它们相互之间的通信,要么通过方法调用,要么通过函数调用来进行。将一个单块系统改造为若干微服务的最大问题,在于对通信模式的改变。仅仅将内存中的方法调用转换为RPC调用这样天真的做法,会导致微服务之间产生繁琐的通信,使得系统表现变糟。取而代之的是,需要用更粗粒度的协议来替代细粒度的服务间通信。

[6]在极度强调高效性(Scale)的情况下,一些组织经常会使用一些二进制的消息发送协议——例如protobuf。即使是这样,这些系统仍然会呈现出“智能端点和傻瓜管道”的特点——来在易读性(transparency)与高效性之间取得平衡。当然,大多数Web属性和绝大多数企业并不需要作出这样的权衡——获得易读性就已经是一个很大的胜利了。

1.5 Decentralized Governance–“去中心化”地治理技术

One of the consequences of centralised governance is the tendency to standardise on single technology platforms. Experience shows that this approach is constricting - not every problem is a nail and not every solution a hammer. We prefer using the right tool for the job and while monolithic applications can take advantage of different languages to a certain extent, it isn’t that common.

使用中心化的方式来对开发进行治理,其中一个后果,就是趋向于在单一技术平台上制定标准。经验表明,这种做法会带来局限性——不是每一个问题都是钉子,不是每一个方案都是锤子。我们更喜欢根据工作的不同来选用合理的工具。尽管那些单块应用系统能在一定程度上利用不同的编程语言,但是这并不常见。

Splitting the monolith’s components out into services we have a choice when building each of them. You want to use Node.js to standup a simple reports page? Go for it. C++ for a particularly gnarly near-real-time component? Fine. You want to swap in a different flavour of database that better suits the read behaviour of one component? We have the technology to rebuild him.

如果能将单块应用的那些组件拆分成多个服务,那么在构建每个服务时,就可以有选择不同技术栈的机会。想要使用Node.js来搞出一个简单的报表页面?尽管去搞。想用C++来做一个特别出彩儿的近乎实时的组件?没有问题。想要换一种不同风格的数据库,来更好地适应一个组件的读取数据的行为?可以重建。

Of course, just because you can do something, doesn’t mean you should - but partitioning your system in this way means you have the option.

Teams building microservices prefer a different approach to standards too. Rather than use a set of defined standards written down somewhere on paper they prefer the idea of producing useful tools that other developers can use to solve similar problems to the ones they are facing. These tools are usually harvested from implementations and shared with a wider group, sometimes, but not exclusively using an internal open source model. Now that git and github have become the de facto version control system of choice, open source practices are becoming more and more common in-house .

当然,仅仅能做事情,并不意味着这些事情就应该被做——不过用微服务的方法把系统进行拆分后,就拥有了技术选型的机会。

相比选用业界一般常用的技术,构建微服务的那些团队更喜欢采用不同的方法。与其选用一组写在纸上已经定义好的标准,他们更喜欢编写一些有用的工具,来让其他开发者能够使用,以便解决那些和他们所面临的问题相似的问题。这些工具通常源自他们的微服务实施过程,并且被分享到更大规模的组织中,这种分享有时会使用内部开源的模式来进行。现在,git和github已经成为事实上的首选版本控制系统。在企业内部,开源的做法正在变得越来越普遍。

Netflix is a good example of an organisation that follows this philosophy. Sharing useful and, above all, battle-tested code as libraries encourages other developers to solve similar problems in similar ways yet leaves the door open to picking a different approach if required. Shared libraries tend to be focused on common problems of data storage, inter-process communication and as we discuss further below, infrastructure automation.

Netflix公司是遵循上述理念的好例子。将实用且经过实战检验的代码以软件库的形式共享出来,能鼓励其他开发人员以相似的方式来解决相似的问题,当然也为在需要的时候选用不同的方案留了一扇门。共享软件库往往集中在解决这样的常见问题,即数据存储、进程间的通信和下面要进一步讨论的基础设施的自动化。

For the microservice community, overheads are particularly unattractive. That isn’t to say that the community doesn’t value service contracts. Quite the opposite, since there tend to be many more of them. It’s just that they are looking at different ways of managing those contracts. Patterns like Tolerant Reader and Consumer-Driven Contracts are often applied to microservices. These aid service contracts in evolving independently. Executing consumer driven contracts as part of your build increases confidence and provides fast feedback on whether your services are functioning. Indeed we know of a team in Australia who drive the build of new services with consumer driven contracts. They use simple tools that allow them to define the contract for a service. This becomes part of the automated build before code for the new service is even written. The service is then built out only to the point where it satisfies the contract - an elegant approach to avoid the ‘YAGNI’[8] dilemma when building new software. These techniques and the tooling growing up around them, limit the need for central contract management by decreasing the temporal coupling between services.

对于微服务社区来说,日常管理开销这一点不是特别吸引人。这并不是说这个社区并不重视服务契约。恰恰相反,它们在社区里出现得更多。这正说明这个社区正在寻找对其进行管理的各种方法。像“容错读取”和“消费者驱动的契约”(Consumer-Driven Contracts)这样的模式,经常被运用到微服务中。这些都有助于服务契约进行独立演进。将执行“消费者驱动的契约”做为软件构建的一部分,能增强开发团队的信心,并提供所依赖的服务是否正常工作的快速反馈。实际上,我们了解到一个在澳洲的团队就是使用“消费者驱动的契约”来驱动构建多个新服务的。他们使用了一些简单的工具,来针对每一个服务定义契约。甚至在新服务的代码编写之前,这件事就已经成为自动化构建的一部分了。接下来服务仅被构建到刚好能满足契约的程度——这是一个在构建新软件时避免YAGNI[9]困境的优雅方法。这些技术和工具在契约周边生长出来,由于减少了服务之间在时域(temporal)上的耦合,从而抑制了对中心契约管理的需求。

SIDEBARS–Many languages, many options–多种编程语言,多种选择可能

The growth of JVM as a platform is just the latest example of mixing languages within a common platform. It’s been common practice to shell-out to a higher level language to take advantage of higher level abstractions for decades. As is dropping down to the metal and writing performance sensitive code in a lower level one. However, many monoliths don’t need this level of performance optimisation nor are DSL’s and higher level abstractions that common (to our dismay). Instead monoliths are usually single language and the tendency is to limit the number of technologies in use [9].

做为一个平台,JVM的发展仅仅是一个将各种编程语言混合到一个通用平台的最新例证。近十年以来,在平台外层实现更高层次的编程语言,来利用更高层次的抽象,已经成为一个普遍做法。同样,在平台底层以更低层次的编程语言编写性能敏感的代码也很普遍。然而,许多单块系统并不需要这种级别的性能优化,另外DSL和更高层次的抽象也不常用(这令我们感到失望)。相反,许多单块应用通常就使用单一编程语言,并且有对所使用的技术数量进行限制的趋势[10]。

Perhaps the apogee of decentralised governance is the build it / run it ethos popularised by Amazon. Teams are responsible for all aspects of the software they build including operating the software 24/7. Devolution of this level of responsibility is definitely not the norm but we do see more and more companies pushing responsibility to the development teams. Netflix is another organisation that has adopted this ethos[10]. Being woken up at 3am every night by your pager is certainly a powerful incentive to focus on quality when writing your code. These ideas are about as far away from the traditional centralized governance model as it is possible to be.

或许去中心化地治理技术的极盛时期,就是亚马逊的“谁构建,谁运行”的风气开始普及的时候。各个团队负责其所构建的软件的所有方面的工作,其中包括7 x 24地对软件进行运维。将运维这一级别的职责下放到团队这种做法,目前绝对不是主流。但是我们确实看到越来越多的公司,将运维的职责交给各个开发团队。Netflix就是已经形成这种风气的另一个组织[11]。避免每天凌晨3点被枕边的寻呼机叫醒,无疑是在程序员编写代码时令其专注质量的强大动力。而这些想法,与那些传统的中心化技术治理的模式具有天壤之别。

[7] 忍不住要提一下Jim Webber的说法:ESB表示Egregious Spaghetti

Box(一盒极烂的意大利面条,http://www.infoq.com/presentations/soa-without-esb)。[8] Netflix让SOA与微服务之间的联系更加明确——直到最近这家公司还将他们的架构风格称为“细粒度的SOA”。

[9] “YAGNI” 或者 “You Aren’t Going To Need

It”(你不会需要它)是极限编程的一条原则(http://c2.com/cgi/wiki?YouArentGonnaNeedIt)和劝诫,指的是“除非到了需要的时候,否则不要添加新功能”。

[10] 单块系统使用单一编程语言,这样讲有点言不由衷——为了在今天的Web上构建各种系统,可能要了解JavaScript、XHTML、CSS、服务器端的编程语言、SQL和一种ORM的方言。很难说只有一种单一编程语言,但是我们的意思你是懂得的。

[11] Adrian Cockcroft在他2013年11月于Flowcon技术大会所做的一次精彩的演讲(http://www.slideshare.net/adrianco/flowcon-added-to-for-cmg-keynote-talk-on-how-speed-wins-and-how-netflix-is-doing-continuous-delivery)中,特别提到了“开发人员自服务”和“开发人员运行他们写的东西”(原文如此)。

1.6 Decentralized Data Management–“去中心化”地管理数据

Decentralization of data management presents in a number of different ways. At the most abstract level, it means that the conceptual model of the world will differ between systems. This is a common issue when integrating across a large enterprise, the sales view of a customer will differ from the support view. Some things that are called customers in the sales view may not appear at all in the support view. Those that do may have different attributes and (worse) common attributes with subtly different semantics.

去中心化地管理数据,其表现形式多种多样。从最抽象的层面看,这意味着各个系统对客观世界所构建的概念模型,将彼此各不相同。当在一个大型的企业中进行系统集成时,这是一个常见的问题。比如对于“客户”这个概念,从销售人员的视角看,就与从支持人员的视角看有所不同。从销售人员的视角所看到的一些被称之为“客户”的事物,或许在支持人员的视角中根本找不到。而那些在两个视角中都能看到的事物,或许各自具有不同的属性。更糟糕的是,那些在两个视角中具有相同属性的事物,或许在语义上有微妙的不同。

SIDEBARS–Battle-tested standards and enforced standards–“实战检验”的标准与“强制执行”的标准

It’s a bit of a dichotomy that microservice teams tend to eschew the kind of rigid enforced standards laid down by enterprise architecture groups but will happily use and even evangelise the use of open standards such as HTTP, ATOM and other microformats.

微服务的下述做法有点泾渭分明的味道,即他们趋向于避开被那些企业架构组织所制定的硬性实施的标准,而愉快地使用甚至传播一些开放标准,比如HTTP、ATOM和其他微格式的协议。

The key difference is how the standards are developed and how they are enforced. Standards managed by groups such as the IETF only become standards when there are several live implementations of them in the wider world and which often grow from successful open-source projects.

这里的关键区别是,这些标准是如何被制定以及如何被实施的。像诸如IETF这样的组织所管理的各种标准,只有达到下述条件才能称为标准,即该标准在全球更广阔的地区有一些正在运行的实现案例,而且这些标准经常源自一些成功的开源项目。

These standards are a world apart from many in a corporate world, which are often developed by groups that have little recent programming experience or overly influenced by vendors.

这些标准组成了一个世界,它区别于来自下述另一个世界的许多标准,即企业世界。企业世界中的标准,经常由这样特点的组织来开发,即缺乏用较新技术进行编程的经验,或受到供应商的过度影响。

This issue is common between applications, but can also occur within applications, particular when that application is divided into separate components. A useful way of thinking about this is the Domain-Driven Design notion of Bounded Context. DDD divides a complex domain up into multiple bounded contexts and maps out the relationships between them. This process is useful for both monolithic and microservice architectures, but there is a natural correlation between service and context boundaries that helps clarify, and as we describe in the section on business capabilities, reinforce the separations.

上述问题在不同的应用程序之间经常出现,同时也会出现在这些应用程序内部,特别是当一个应用程序被分成不同的组件时就会出现。思考这类问题的一个有用的方法,就是使用领域驱动设计(Domain-Driven Design, DDD)中的“限界上下文”(Bounded Context)的概念。DDD将一个复杂的领域划分为多个限界上下文,并且将其相互之间的关系用图画出来。这一划分过程对于单块和微服务架构两者都是有用的,而且就像前面有关“业务功能”一节中所讨论的那样,在服务和各个限界上下文之间所存在的自然的联动关系,能有助于澄清和强化这种划分。

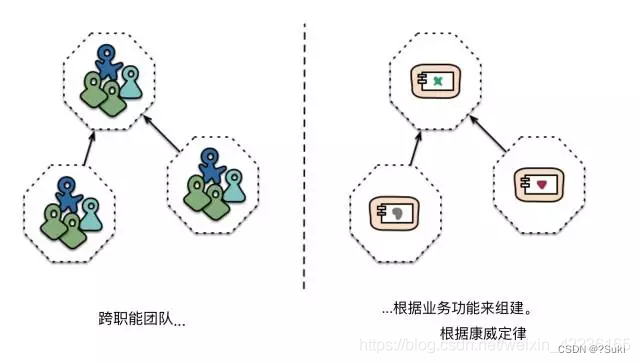

As well as decentralizing decisions about conceptual models, microservices also decentralize data storage decisions. While monolithic applications prefer a single logical database for persistant data, enterprises often prefer a single database across a range of applications - many of these decisions driven through vendor’s commercial models around licensing. Microservices prefer letting each service manage its own database, either different instances of the same database technology, or entirely different database systems - an approach called Polyglot Persistence. You can use polyglot persistence in a monolith, but it appears more frequently with microservices.

如同在概念模型上进行去中心化的决策一样,微服务也在数据存储上进行去中心化的决策。尽管各个单块应用更愿意在逻辑上各自使用一个单独的数据库来持久化数据,但是各家企业往往喜欢一系列单块应用共用一个单独的数据库——许多这样的决策是被供应商的各种版权商业模式所驱动出来的。微服务更喜欢让每一个服务来管理其自有数据库。其实现可以采用相同数据库技术的不同数据库实例,也可以采用完全不同的数据库系统。这种方法被称作“多语种持久化”(Polyglot Persistence)。在一个单块系统中也能使用多语种持久化,但是看起来这种方法在微服务中出现得更加频繁。

Decentralizing responsibility for data across microservices has implications for managing updates. The common approach to dealing with updates has been to use transactions to guarantee consistency when updating multiple resources. This approach is often used within monoliths.

在各个微服务之间将数据的职责进行“去中心化”的管理,会影响软件更新的管理。处理软件更新的常用方法,是当更新多个资源的时候,使用事务来保证一致性。这种方法经常在单块系统中被采用。

Using transactions like this helps with consistency, but imposes significant temporal coupling, which is problematic across multiple services. Distributed transactions are notoriously difficult to implement and as a consequence microservice architectures emphasize transactionless coordination between services, with explicit recognition that consistency may only be eventual consistency and problems are dealt with by compensating operations.

像这样地使用事务,有助于保持数据一致性。但是在时域上会引发明显的耦合,这样当在多个服务之间处理事务时会出现一致性问题。分布式事务实现起来难度之大是臭名远扬的。为此,微服务架构更强调在各个服务之间进行“无事务”的协调。这源自微服务社区明确地认识到下述两点,即数据一致性可能只要求数据在最终达到一致,并且一致性问题能够通过补偿操作来进行处理。

Choosing to manage inconsistencies in this way is a new challenge for many development teams, but it is one that often matches business practice. Often businesses handle a degree of inconsistency in order to respond quickly to demand, while having some kind of reversal process to deal with mistakes. The trade-off is worth it as long as the cost of fixing mistakes is less than the cost of lost business under greater consistency.

对于许多开发团队来说,选择这种方式来管理数据的“非一致性”,是一个新的挑战。但这也经常符合在商业上的实践做法。通常情况下,为了快速响应需求,商家们都会处理一定程度上的数据“非一致性”,来通过做某种反向过程进行错误处理。只要修复错误的成本,与在保持更大的数据一致性却导致丢了生意所产生的成本相比,前者更低,那么这种“非一致性”地管理数据的权衡就是值得的。

1.7 Infrastructure Automation–“基础设施”自动化

Infrastructure automation techniques have evolved enormously over the last few years - the evolution of the cloud and AWS in particular has reduced the operational complexity of building, deploying and operating microservices.

基础设施自动化技术在过去几年里已经得到长足的发展。云的演进,特别是AWS的发展,已经降低了构建、部署和运维微服务的操作复杂性。

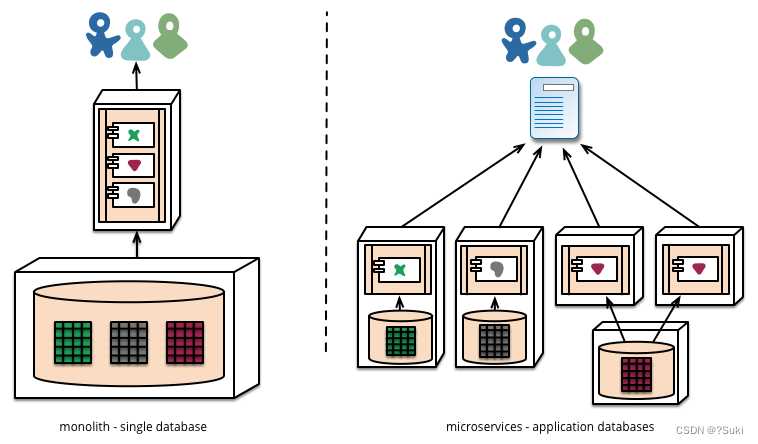

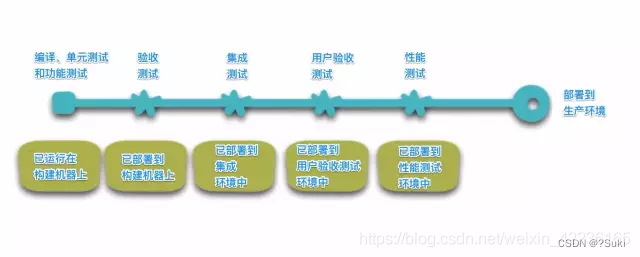

Many of the products or systems being build with microservices are being built by teams with extensive experience of Continuous Delivery and it’s precursor, Continuous Integration. Teams building software this way make extensive use of infrastructure automation techniques. This is illustrated in the build pipeline shown below.

许多使用微服务构建的产品和系统,正在被这样的团队所构建,即他们都具备极其丰富的“持续交付”和其前身“持续集成”的经验。用这种方法构建软件的各个团队,广泛采用了基础设施的自动化技术。如下图的构建流水线所示:

Since this isn’t an article on Continuous Delivery we will call attention to just a couple of key features here. We want as much confidence as possible that our software is working, so we run lots of automated tests. Promotion of working software ‘up’ the pipeline means we automate deployment to each new environment.

因为本文并不是一篇有关持续交付的文章,所以下面仅提请大家注意两个持续交付的关键特点。为了尽可能地获得对正在运行的软件的信心,需要运行大量的自动化测试。让可工作的软件达到“晋级”(Promotion)状态从而“推上”流水线,就意味着可以在每一个新的环境中,对软件进行自动化部署。

SIDEBARS–Make it easy to do the right thing–让“方向正确地做事”更容易

One side effect we have found of increased automation as a consequence of continuous delivery and deployment is the creation of useful tools to help developers and operations folk. Tooling for creating artefacts, managing codebases, standing up simple services or for adding standard monitoring and logging are pretty common now. The best example on the web is probably Netflix’s set of open source tools, but there are others including Dropwizard which we have used extensively.

那些因实现持续交付和持续集成所增加的自动化工作的副产品,是创建一些对开发和运维人员有用的工具。现在,能完成下述工作的工具已经相当常见了,即创建工件(artefacts)、管理代码库、启动一些简单的服务、或增加标准的监控和日志功能。Web上最好的例子可能是Netflix提供的一套开源工具集,但也有其他一些好工具,包括我们已经广泛使用的Dropwizard 。

A monolithic application will be built, tested and pushed through these environments quite happlily. It turns out that once you have invested in automating the path to production for a monolith, then deploying more applications doesn’t seem so scary any more. Remember, one of the aims of CD is to make deployment boring, so whether its one or three applications, as long as its still boring it doesn’t matter[12].

一个单块应用程序,能够相当愉快地在上述各个环境中,被构建、测试和推送。其结果是,一旦在下述工作上进行了投入,即针对一个单块系统将其通往生产环境的通道进行自动化,那么部署更多的应用系统似乎就不再可怕。记住,持续交付的目的之一,是让“部署”工作变得“无聊”。所以不管是一个还是三个应用系统,只要部署工作依旧很“无聊”,那么就没什么可担心的了[12]。

Another area where we see teams using extensive infrastructure automation is when managing microservices in production. In contrast to our assertion above that as long as deployment is boring there isn’t that much difference between monoliths and microservices, the operational landscape for each can be strikingly different.

我们所看到的各个团队在广泛使用基础设施自动化实践的另一个领域,是在生产环境中管理各个微服务。与前面我们对比单块系统和微服务所说的正相反,只要部署工作很无聊,那么在这一点上单块系统和微服务就没什么区别。然而,两者在运维领域的情况却截然不同。

[12] 这里我们又有点言不由衷了。 很明显,在更复杂的网络拓扑里,部署更多的服务,会比部署一个单独的单块系统要更加困难。幸运的是,有一些模式能够减少其中的复杂性——但对于工具的投资还是必须的。

1.8 Design for failure–“容错”设计

A consequence of using services as components, is that applications need to be designed so that they can tolerate the failure of services. Any service call could fail due to unavailability of the supplier, the client has to respond to this as gracefully as possible. This is a disadvantage compared to a monolithic design as it introduces additional complexity to handle it. The consequence is that microservice teams constantly reflect on how service failures affect the user experience. Netflix’s Simian Army induces failures of services and even datacenters during the working day to test both the application’s resilience and monitoring.

使用各个微服务来替代组件,其结果是各个应用程序需要设计成能够容忍这些服务所出现的故障。如果服务提供方不可用,那么任何对该服务的调用都会出现故障。客户端要尽可能优雅地应对这种情况。与一个单块设计相比,这是一个劣势。因为这会引人额外的复杂性来处理这种情况。为此,各个微服务团队在不断地反思:这些服务故障是如何影响用户体验的。Netflix公司所研发的开源测试工具Simian Army,能够诱导服务发生故障,甚至能诱导一个数据中心在工作日发生故障,来测试该应用的弹性和监控能力。

SIDEBARS–The circuit breaker and production ready code–"断路器"与“可随时上线的代码”

Circuit Breaker appears in Release It! alongside other patterns such as Bulkhead and Timeout. Implemented together, these patterns are crucially important when building communicating applications. This Netflix blog entry does a great job of explaining their application of them.

“断路器”(Circuit Breaker)一词与其他一些模式一起出现在《发布!》(Release It!)一书中,例如隔板(Bulkhead)和超时(Timeout)。当构建彼此通信的应用系统时,将这些模式加以综合运用就变得至关重要。Netflix公司的这篇很精彩的博客解释了这些模式是如何应用的。

This kind of automated testing in production would be enough to give most operation groups the kind of shivers usually preceding a week off work. This isn’t to say that monolithic architectural styles aren’t capable of sophisticated monitoring setups - it’s just less common in our experience.

这种在生产环境中所进行的自动化测试,能足以让大多数运维组织兴奋得浑身颤栗,就像在一周的长假即将到来前那样。这并不是说单块架构风格不能构建先进的监控系统——只是根据我们的经验,这在单块系统中并不常见罢了。

Since services can fail at any time, it’s important to be able to detect the failures quickly and, if possible, automatically restore service. Microservice applications put a lot of emphasis on real-time monitoring of the application, checking both architectural elements (how many requests per second is the database getting) and business relevant metrics (such as how many orders per minute are received). Semantic monitoring can provide an early warning system of something going wrong that triggers development teams to follow up and investigate.

因为各个服务可以在任何时候发生故障,所以下面两件事就变得很重要,即能够快速地检测出故障,而且在可能的情况下能够自动恢复服务。各个微服务的应用都将大量的精力放到了应用程序的实时监控上,来检查“架构元素指标”(例如数据库每秒收到多少请求)和 “业务相关指标”(例如系统每分钟收到多少订单)。当系统某个地方出现问题,语义监控系统能提供一个预警,来触发开发团队进行后续的跟进和调查工作。

This is particularly important to a microservices architecture because the microservice preference towards choreography and event collaboration leads to emergent behavior. While many pundits praise the value of serendipitous emergence, the truth is that emergent behavior can sometimes be a bad thing. Monitoring is vital to spot bad emergent behavior quickly so it can be fixed.

这对于一个微服务架构是尤其重要的,因为微服务对于服务编制(choreography)和事件协作的偏好,会导致“突发行为”。尽管许多权威人士对于偶发事件的价值持积极态度,但事实上,“突发行为”有时是一件坏事。在能够快速发现有坏处的“突发行为”并进行修复的方面,监控是至关重要的。

SIDEBARS–Synchronous calls considered harmful–“同步调用”有害

Any time you have a number of synchronous calls between services you will encounter the multiplicative effect of downtime. Simply, this is when the downtime of your system becomes the product of the downtimes of the individual components. You face a choice, making your calls asynchronous or managing the downtime. At www.guardian.co.uk they have implemented a simple rule on the new platform - one synchronous call per user request while at Netflix, their platform API redesign has built asynchronicity into the API fabric.

一旦在一些服务之间进行多个同步调用,就会遇到宕机的乘法效应。简而言之,这意味着整个系统的宕机时间,是每一个单独模块各自宕机时间的乘积。此时面临着一个选择:是让模块之间的调用异步,还是去管理宕机时间?在英国卫报网站www.guardian.co.uk,他们在新平台上实现了一个简单的规则——每一个用户请求都对应一个同步调用。然而在Netflix公司,他们重新设计的平台API将异步性构建到API的机制(fabric)中。

Monoliths can be built to be as transparent as a microservice - in fact, they should be. The difference is that you absolutely need to know when services running in different processes are disconnected. With libraries within the same process this kind of transparency is less likely to be useful.

单块系统也能构建得像微服务那样来实现透明的监控系统——实际上,它们也应该如此。差别是,绝对需要知道那些运行在不同进程中的服务,在何时断掉了。而如果在同一个进程内使用软件库的话,这种透明的监控系统就用处不大了。

Microservice teams would expect to see sophisticated monitoring and logging setups for each individual service such as dashboards showing up/down status and a variety of operational and business relevant metrics. Details on circuit breaker status, current throughput and latency are other examples we often encounter in the wild.

那些微服务团队希望在每一个单独的服务中,都能看到先进的监控和日志记录装置。例如显示“运行/宕机”状态的仪表盘,和各种运维和业务相关的指标。另外我们经常在工作中会碰到这样一些细节,即断路器的状态、当前的吞吐率和延迟,以及其他一些例子。

1.9 Evolutionary Design–“演进式”设计

Microservice practitioners, usually have come from an evolutionary design background and see service decomposition as a further tool to enable application developers to control changes in their application without slowing down change. Change control doesn’t necessarily mean change reduction - with the right attitudes and tools you can make frequent, fast, and well-controlled changes to software.

那些微服务的从业者们,通常具有演进式设计的背景,而且通常将服务的分解,视作一个额外的工具,来让应用开发人员能够控制应用系统中的变化,而无须减少变化的发生。变化控制并不一定意味着要减少变化——在正确的态度和工具的帮助下,就能在软件中让变化发生得频繁、快速且经过了良好的控制。

Whenever you try to break a software system into components, you’re faced with the decision of how to divide up the pieces - what are the principles on which we decide to slice up our application? The key property of a component is the notion of independent replacement and upgradeability[13] - which implies we look for points where we can imagine rewriting a component without affecting its collaborators. Indeed many microservice groups take this further by explicitly expecting many services to be scrapped rather than evolved in the longer term.

每当试图要将软件系统分解为各个组件时,就会面临这样的决策,即如何进行切分——我们决定切分应用系统时应该遵循的原则是什么?一个组件的关键属性,是具有独立更换和升级的特点[13]——这意味着,需要寻找这些点,即想象着能否在其中一个点上重写该组件,而无须影响该组件的其他合作组件。事实上,许多做微服务的团队会更进一步,他们明确地预期许多服务将来会报废,而不是守着这些服务做长期演进。

The Guardian website is a good example of an application that was designed and built as a monolith, but has been evolving in a microservice direction. The monolith still is the core of the website, but they prefer to add new features by building microservices that use the monolith’s API. This approach is particularly handy for features that are inherently temporary, such as specialized pages to handle a sporting event. Such a part of the website can quickly be put together using rapid development languages, and removed once the event is over. We’ve seen similar approaches at a financial institution where new services are added for a market opportunity and discarded after a few months or even weeks.

英国卫报网站是一个好例子。原先该网站是一个以单块系统的方式来设计和构建的应用系统,然而它已经开始向微服务方向进行演进了。原先的单块系统依旧是该网站的核心,但是在添加新特性时他们愿意以构建一些微服务的方式来进行添加,而这些微服务会去调用原先那个单块系统的API。当在开发那些本身就带有临时性特点的新特性时,这种方法就特别方便,例如开发那些报道一个体育赛事的专门页面。当使用一些快速的开发语言时,像这样的网站页面就能被快速地整合起来。而一旦赛事结束,这样页面就可以被删除。在一个金融机构中,我们已经看到了一些相似的做法,即针对一个市场机会,一些新的服务可以被添加进来。然后在几个月甚至几周之后,这些新服务就作废了。

This emphasis on replaceability is a special case of a more general principle of modular design, which is to drive modularity through the pattern of change [13]. You want to keep things that change at the same time in the same module. Parts of a system that change rarely should be in different services to those that are currently undergoing lots of churn. If you find yourself repeatedly changing two services together, that’s a sign that they should be merged.

这种强调可更换性的特点,是模块化设计一般性原则的一个特例,通过“变化模式”(pattern of change)[14]来驱动进行模块化的实现。大家都愿意将那些能在同时发生变化的东西,放到同一个模块中。系统中那些很少发生变化的部分,应该被放到不同的服务中,以区别于那些当前正在经历大量变动(churn)的部分。如果发现需要同时反复变更两个服务时,这就是它们两个需要被合并的一个信号。

Putting components into services adds an opportunity for more granular release planning. With a monolith any changes require a full build and deployment of the entire application. With microservices, however, you only need to redeploy the service(s) you modified. This can simplify and speed up the release process. The downside is that you have to worry about changes to one service breaking its consumers. The traditional integration approach is to try to deal with this problem using versioning, but the preference in the microservice world is to only use versioning as a last resort. We can avoid a lot of versioning by designing services to be as tolerant as possible to changes in their suppliers.

把一个个组件放入一个个服务中,增大了作出更加精细的软件发布计划的机会。对于一个单块系统,任何变化都需要做一次整个应用系统的全量构建和部署。然而,对于一个个微服务来说,只需要重新部署修改过的那些服务就够了。这能简化并加快发布过程。但缺点是:必须要考虑当一个服务发生变化时,依赖它并对其进行消费的其他服务将无法工作。传统的集成方法是试图使用版本化来解决这个问题。但在微服务世界中,大家更喜欢将版本化作为最后万不得已的手段来使用。我们可以通过下述方法来避免许多版本化的工作,即把各个服务设计得尽量能够容错,来应对其所依赖的服务所发生的变化。

[13] 事实上,Dan North将这种架构风格称作“可更换的组件架构”,而不是微服务。因为这看起来似乎是在谈微服务特性的一个子集,所以我们选择将其归类为微服务。

[14] Kent Beck在《实现模式》(Implementation

Patterns)一书中,将其作为他的一条设计原则而强调出来。

2 Are Microservices the Future? --未来的方向是“微服务”吗?

Our main aim in writing this article is to explain the major ideas and principles of microservices. By taking the time to do this we clearly think that the microservices architectural style is an important idea - one worth serious consideration for enterprise applications. We have recently built several systems using the style and know of others who have used and favor this approach.

我们写这篇文章的主要目的,是来解释有关微服务的主要思路和原则。在花了一点时间做了这件事后,我们清楚地认识到,微服务架构风格是一个重要的理念——在研发企业应用系统时,值得对它进行认真考虑。我们最近已经使用这种风格构建了一些系统,并且了解到其他一些团队也在已经使用并赞同这种方法。

Microservice Trade-Offs

Many development teams have found the microservices architectural style to be a superior approach to a monolithic architecture. But other teams have found them to be a productivity-sapping burden. Like any architectural style, microservices bring costs and benefits. To make a sensible choice you have to understand these and apply them to your specific context.

许多开发团队发现微服务架构风格是优于单体架构的方法。但其他团队发现它们是一种降低生产力的负担。与任何架构风格一样,微服务带来成本和收益。要做出明智的选择,您必须了解这些并将它们应用到您的特定环境中。

Those we know about who are in some way pioneering the architectural style include Amazon, Netflix, The Guardian, the UK Government Digital Service, realestate.com.au, Forward and comparethemarket.com. The conference circuit in 2013 was full of examples of companies that are moving to something that would class as microservices - including Travis CI. In addition there are plenty of organizations that have long been doing what we would class as microservices, but without ever using the name. (Often this is labelled as SOA - although, as we’ve said, SOA comes in many contradictory forms. [15])

我们所了解到的那些在某种程度上做为这种架构风格的实践先驱包括:亚马逊、Netflix、英国卫报、英国政府数字化服务中心、realestate.com.au、Forward和comparethemarket.com。在2013年的技术大会圈子充满了各种各样的正在转向可归类为微服务的公司案例——包括Travis CI。另外还有大量的组织,它们长期以来一直在做着我们可以归类为微服务的产品,却从未使用过这个名字(这通常被标记为SOA——尽管正如我们所说,SOA会表现出各种自相矛盾的形式[15])。

Despite these positive experiences, however, we aren’t arguing that we are certain that microservices are the future direction for software architectures. While our experiences so far are positive compared to monolithic applications, we’re conscious of the fact that not enough time has passed for us to make a full judgement.

尽管有这些正面的经验,然而并不是说我们确信微服务是软件架构的未来的方向。尽管到目前为止,与单块应用系统相比,我们对于所经历过的微服务的评价是积极的,但是我们也意识到这样的事实,即能供我们做出完整判断的时间还不够长。

Often the true consequences of your architectural decisions are only evident several years after you made them. We have seen projects where a good team, with a strong desire for modularity, has built a monolithic architecture that has decayed over the years. Many people believe that such decay is less likely with microservices, since the service boundaries are explicit and hard to patch around. Yet until we see enough systems with enough age, we can’t truly assess how microservice architectures mature.

通常,架构决策所产生的真正效果,只有在该决策做出若干年后才能真正显现。我们已经看到由带着强烈的模块化愿望的优秀团队所做的一些项目,最终却构建出一个单块架构,并在几年之内不断腐化。许多人认为,如果使用微服务就不大可能出现这种腐化,因为服务的边界是明确的,而且难以随意搞乱。然而,对于那些开发时间足够长的各种系统,除非我们已经见识得足够多,否则我们无法真正评价微服务架构是如何成熟的。

There are certainly reasons why one might expect microservices to mature poorly. In any effort at componentization, success depends on how well the software fits into components. It’s hard to figure out exactly where the component boundaries should lie. Evolutionary design recognizes the difficulties of getting boundaries right and thus the importance of it being easy to refactor them. But when your components are services with remote communications, then refactoring is much harder than with in-process libraries. Moving code is difficult across service boundaries, any interface changes need to be coordinated between participants, layers of backwards compatibility need to be added, and testing is made more complicated.

有人觉得微服务或许很难成熟起来,这当然是有原因的。在组件化上所做的任何工作的成功与否,取决于软件与组件的匹配程度。准确地搞清楚某个组件的边界的位置应该出现在哪里,是一件困难的工作。演进式设计承认难以对边界进行正确定位,所以它将工作的重点放到了易于对边界进行重构之上。但是当各个组件成为各个进行远程通信的服务后,比起在单一进程内进行各个软件库之间的调用,此时的重构就变得更加困难。跨越服务边界的代码移动就变得困难起来。接口的任何变化,都需要在其各个参与者之间进行协调。向后兼容的层次也需要被添加进来。测试也会变得更加复杂。

Our colleague Sam Newman spent most of 2014 working on a book that captures our experiences with building microservices. This should be your next step if you want a deeper dive into the topic.

我们的同事Sam Newman花了2014年的大部分时间撰写了一本书,来记述我们构建微服务的经验。如果想对这个话题深入下去,下一步就应该是阅读这本书。

Another issue is If the components do not compose cleanly, then all you are doing is shifting complexity from inside a component to the connections between components. Not just does this just move complexity around, it moves it to a place that’s less explicit and harder to control. It’s easy to think things are better when you are looking at the inside of a small, simple component, while missing messy connections between services.

另一个问题是,如果这些组件不能干净利落地组合成一个系统,那么所做的一切工作,仅仅是将组件内的复杂性转移到组件之间的连接之上。这样做的后果,不仅仅是将复杂性搬了家,它还将复杂性转移到那些不再明确且难以控制的边界之上。当在观察一个小型且简单的组件内部时,人们很容易觉得事情已经变得更好了,然而他们却忽视了服务之间杂乱的连接。

Finally, there is the factor of team skill. New techniques tend to be adopted by more skillful teams. But a technique that is more effective for a more skillful team isn’t necessarily going to work for less skillful teams. We’ve seen plenty of cases of less skillful teams building messy monolithic architectures, but it takes time to see what happens when this kind of mess occurs with microservices. A poor team will always create a poor system - it’s very hard to tell if microservices reduce the mess in this case or make it worse.

最后,还有一个团队技能的因素。新技术往往会被技术更加过硬的团队所采用。对于技术更加过硬的团队而更有效的一项技术,不一定适用于一个技术略逊一筹的团队。我们已经看到大量这样的案例,那些技术略逊一筹的团队构建出了杂乱的单块架构。当这种杂乱发生到微服务身上时,会出现什么情况?这需要花时间来观察。一个糟糕的团队,总会构建一个糟糕的系统——在这种情况下,很难讲微服务究竟是减少了杂乱,还是让事情变得更糟。

One reasonable argument we’ve heard is that you shouldn’t start with a microservices architecture. Instead begin with a monolith, keep it modular, and split it into microservices once the monolith becomes a problem. (Although this advice isn’t ideal, since a good in-process interface is usually not a good service interface.)

我们听到一个合理的说法,是说不要一上来就以微服务架构做为起点。相反,要用一个单块系统做为起点,并保持其模块化。当这个单块系统出现了问题后,再将其分解为微服务。(尽管这个建议并不理想,因为一个良好的单一进程内的接口,通常不是一个良好的服务接口。)

So we write this with cautious optimism. So far, we’ve seen enough about the microservice style to feel that it can be a worthwhile road to tread. We can’t say for sure where we’ll end up, but one of the challenges of software development is that you can only make decisions based on the imperfect information that you currently have to hand.

因此,我们持谨慎乐观的态度来撰写此文。到目前为止,我们已经看到足够多的有关微服务风格的事物,并且觉得这是一条有价值去跋涉的道路。我们不能肯定地说,道路的尽头在哪里。但是,软件开发的挑战之一,就是只能基于“目前手上拥有但还不够完善”的信息来做出决策。

[15] SOA很难讲是这段历史的根源。当SOA这个词儿在本世纪初刚刚出现时,我记得有人说:“我们很多年以来一直是这样做的。”有一派观点说,SOA这种风格,将企业级计算早期COBOL程序通过数据文件来进行通信的方式,视作自己的“根”。在另一个方向上,有人说“Erlang编程模型”与微服务是同一回事,只不过它被应用到一个企业应用的上下文中去了。

3 References–参考资料

请进入最下方。

By – Suki整理

1695

1695

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?