由于巴比特上的谋篇关于RSA的文章翻译不全,所以将原文拷贝过来,方便无法翻墙的同学观看。Deep Dive on RSA Accumulators – Georgios Konstantopoulos – Medium

Preface

In this post, I will attempt to make a deep dive on RSA Accumulators while providing a review of the recently released paper by Stanford’s Applied Cryptography Group, Batching Techniques for Accumulators with Applications to IOPs and Stateless Blockchains, by Benedikt Bunz, Ben Fischand Dan Boneh.

I highly suggest you go through the math by hand for your better understanding.

Background

Accumulators are a topic of interest in academia since 1994. Similarly to a Merkle Tree, they are used to cryptographically commit to the knowledge of a set of data. At a later point in time, proving membership of a subset of the dataset in the dataset can be proven by publishing a proof. In Merkle Trees the proof is called a Merkle Branch (or Merkle Proof), and grows logarithmically to the size of the committed data (commit 16 elements, prove inclusion by revealing log_2(16)=4).

Accumulators on the other hand, allow proving membership in constant size, as well as batching of proofs for multiple elements (which is not a feature of Merkle trees).

The focus of this post will be on describing the building blocks of RSA Accumulators, how we can construct proofs of (non-)membership as well as batch them across multiple blocks. This particular technique also has applications in UTXO-Based Plasma, and has given birth to the Plasma Primevariant. A lot of effort is being put into designing an accumulator that allows compaction of the UTXO-set in Plasma.

Disclaimer: My notation is slightly loose in this post for simplicity’s sake (eg not including that $u,w \in G$ or

mod N for modular arithmetic).

Glossary (definitions from [1]):

Accumulator: “A cryptographic accumulator is a primitive that produces a short binding commitment to a set of elements together with short membership/non-membership proofs for any element in the set.”

Dynamic Accumulator: “Accumulator which supports addition/deletion of elements with O(1) cost, independent of the number of accumulated elements”

Universal Accumulator: “Dynamic Accumulator which supports membership and non-membership proofs”

Batching: Batch verify n proofs faster than verifying a single proof n times

Aggregating: Aggregate n membership roofs in a single constant size proof

Group of Unknown Order: The order of a group is the number of elements in its set. Generating a group of unknown order is required for the security of the provided proofs (otherwise the modulo used in the accumulators has a known factorization and fake proofs can be created). Generating it can be done through a multi party computation, but that is insecure if the generating parties are colluding to retrieve the factorization of the generated number. It can be generated without a trusted setup through the usage of class groups.

Succinct Proofs for Hidden Order Groups

Wesolowski in [2], proposes a proof of knowledge of exponent scheme, where a Prover is trying to convince a Verifier that they know a number x such that, with a known base u, u^x = w holds.

Let’s take an example, with base 2 (u=2), and w=16, it would be x=4. How do we do that? We transmit x to the Verifier, they have to perform 2⁴, and check the result against w. If it matches, they’re convinced. The two steps that seem obvious here are:

- the Verifier has to perform u^x: This is a costly operation for large numbers

- transmitting x to the Verifier: x might be large, and thus the bandwidth required to transmit it may be non-trivial.

Let’s see what protocols are being proposed to tackle this challenge. These protocols are all interactive, meaning the Verifier and the Prover send each other “challenges” that are used in subsequent steps of the protocol, to make it secure.

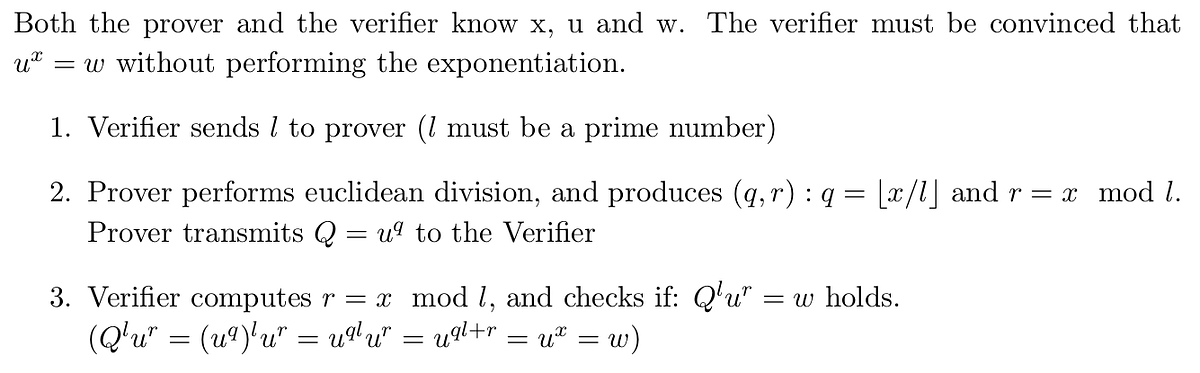

Proof of Exponentiation (PoE, section 3.1)

First, let’s see how we can convince the Verifier, without them actually having to run the whole exponentiation.

Proof of Exponentiation (note: current revision of the paper has a typo, and sets Q=g^q instead of u^q in page 8.

Proof of Exponentiation (note: current revision of the paper has a typo, and sets Q=g^q instead of u^q in page 8.

The protocol is useful, only if the Verifier is able to compute the residue r faster than computing u^x. It solves the exponentiation issue, but still requires that the prover transmits a potentially large x to the verifier, or that x is publicly known.

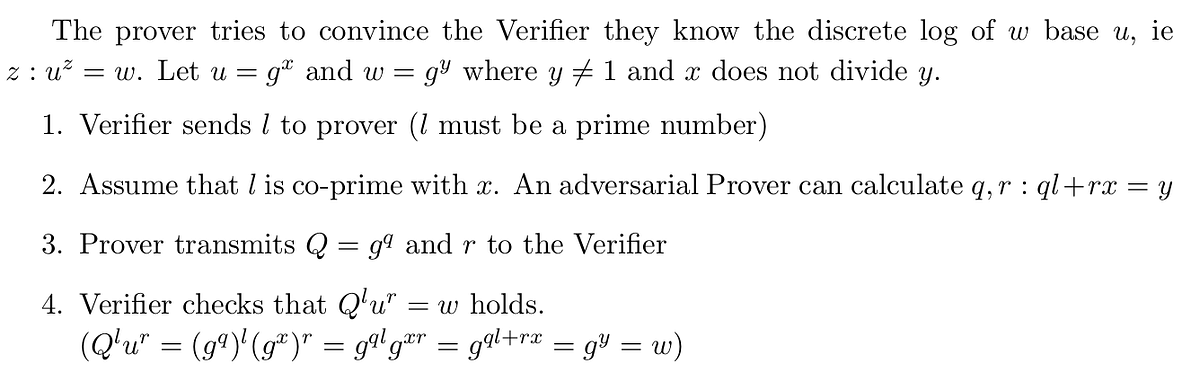

Proof of Knowledge of Discrete Log (PoKE, section 3.3)

Instead of transmitting x, we can instead transmit r. The proof becomes (Q,r) and the Verifier must additionally check that r is less than l (PoKE* protocol). This is insecure when the adversary can freely choose the base u!

The verifier got fooled by the Prover that they know z: u^z=w, without knowing z!

The detail that breaks the protocol here, is that the Prover picks the base u=g^x, so that x is co-prime with l.

We can be sure that the above protocol works for a base g which is fixed and encoded in the Common Reference String (CRS) — in simpler terms, all parties agree on the base g beforehand and it cannot be chosen arbitrarily by an adversary.

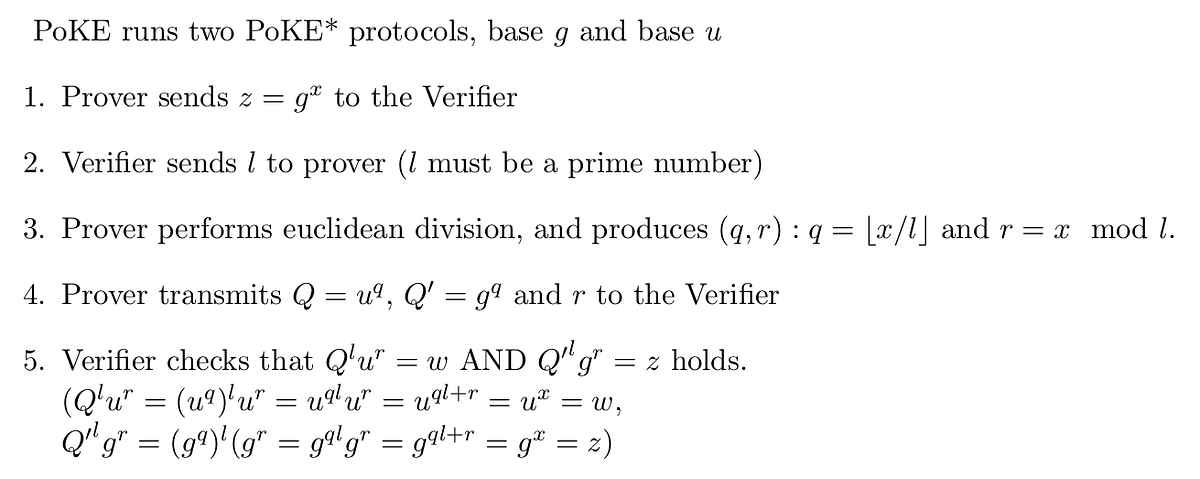

The protocol can be fixed by:

- Proving knowledge of the discrete logarithm x of z = g^x, for a fixed g

- Prove that the same x is also the discrete logarithm of w base u.

So the final protocol (PoKE) is:

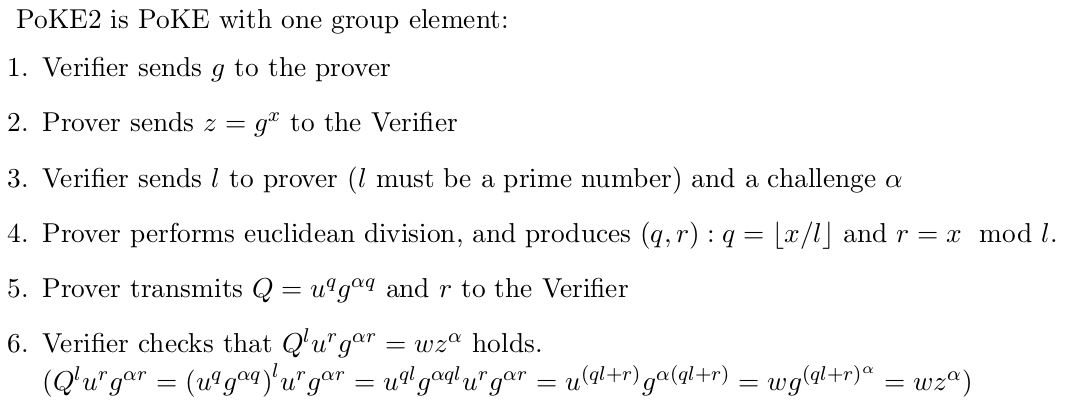

Proof is now 2 group elements, Q and Q’. Can we do better?

Reducing the proof to one group element can be done by adding an additional interactive step:

The verifier needs to send an additional challenge \alpha so that the prover cannot create fake proofs

Why does the challenge have to be a prime number?

The challenge l used in PoE, PoKE, PoKE2 (and their non-interactive variants), must be a prime number which is either provided as a challenge from the Verifier, or is produced by the prover through a collision resistant hash function that maps to a prime number domain (more on this in the next section). Why is that?

Huge thanks to Benedikt Bunz for taking the time to explain this attack to me.

In fact, the challenge l does not have to be a prime number, but it must have a large prime factor that is hard to predict.

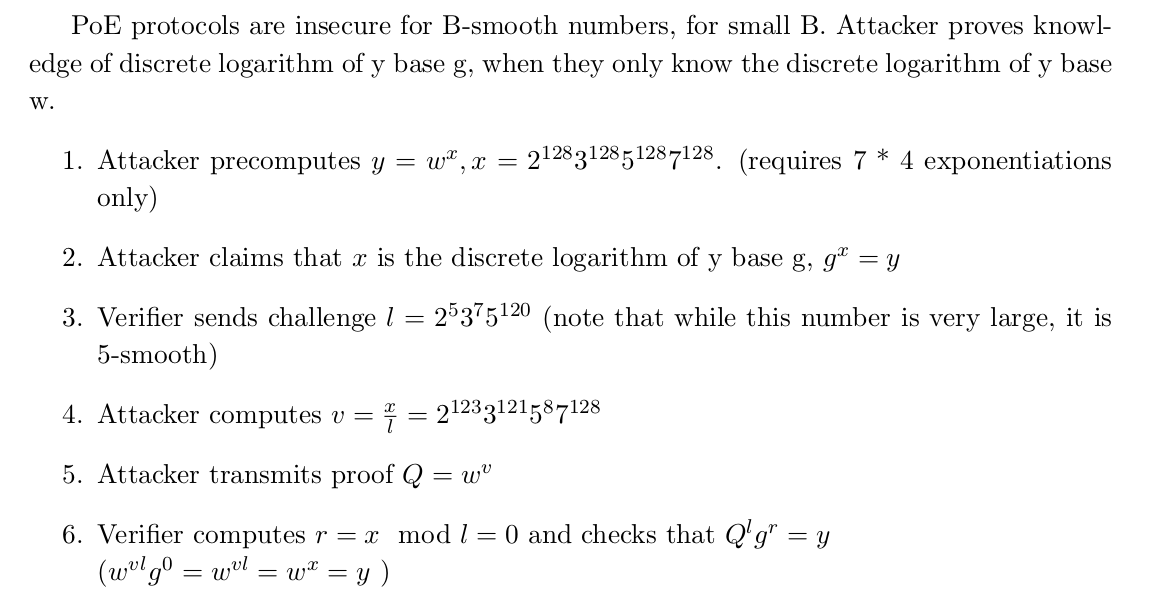

Let’s attack the PoE protocol, when l has small prime factors (we also call these numbers B-smooth numbers):

A 5-smooth challenge is weak and enables an attacker to fool a Verifier about knowledge of a discrete logarithm

The attacker successfully fooled the Verifier into believing they know the discrete logarithm of y base g, when they only knew the discrete logarithm of y base w.

The above attack would not work if the challenge had a large prime factor which the attacker wasn’t able to predict.

To avoid this attack, we just set the challenge to be a large prime number the attacker cannot predict in advance. For RSA Accumulators as we’ll see later, the challenge must be larger than any of the accumulated primes (otherwise the above precomputation attack becomes trivial).

From Interactive to Non-Interactive Proofs.

Using the Fiat-Shamir heuristic, any interactive protocol can be turned into non-interactive, in the random oracle model (assuming we have a secure generator of randomness, such as a secure cryptographic hash function).

PoKE2 requires two steps of interaction, one to give a generator g selected by the Verifier to the Prover, and one to send the challenges l and a. Instead, we can hash the current “transcript” and use the output as these values. Since we are operating in the random oracle model, it does not make a difference if these values were picked by the Verifier to prevent the Prover from cheating, or if they come from a hash function, since the two should be statistically indistinguishable!

Each side generates the challenge parameters without interaction, each time by using the hash function and the current transcript of the protocol

The above techniques involve proving knowledge of a preimage for the function w = f(x) = u^x , for scalar values.

The techniques can also be extended to support proofs of knowledge of a homomorphism preimage , ie prove knowledge of length-n vector x such that φ( x ) = w.

They can also be performed in zero-knowledge. PoKE requires sending g^x, for a known g. When verifying the correctness of a protocol, we assume the existence of a Simulator who is able to simulate g^x by knowing the witness x. This leaks information and is thus not zero-knowledge! The technique used by the authors involves blinding the inputs which are being proven by utilizing a Schnorr-like protocol and Pedersen Commitments.

Take a detour here if you’re not familiar with these terms.

The RSA Accumulator

We gave the definition of an accumulator in the glossary. We will now discuss the construction of a universal accumulator which supports batched membership proofs, and non-membership proofs.

Constructing the accumulator, requires picking a modulus N from a group of unknown order, which can be picked from an RSA Group (e.g. RSA-2048, if you trust RSA Laboratories), or generated through a trusted setup.

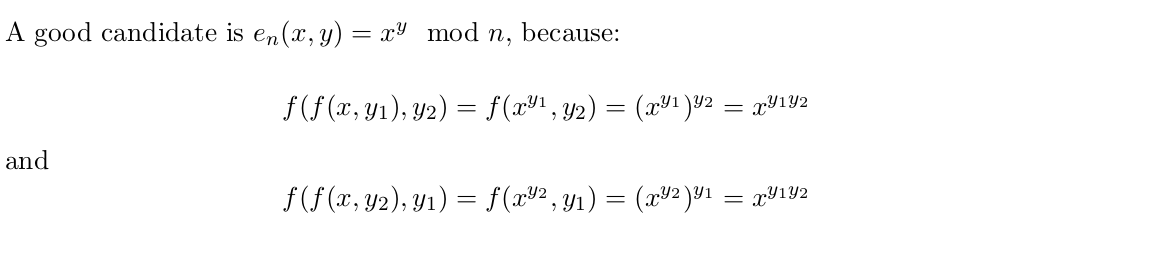

The initial state of the RSA Accumulator is the generator sampled from the group of unknown order, g and implies that the list of elements in the accumulator is empty [].

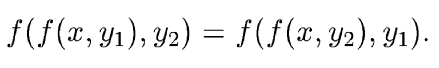

As pointed in [3], an accumulator must have the quasi-commutative mathematical property.

Quasi-commutative property for two elements.

Adding an element x to an accumulator A is done by raising the accumulator to the element: A’ = A^x mod N . (I’ll omit the mod N from here on for simplicity)

Proving Membership

Proving membership of an element in an accumulator requires revealing the value of the element, and a witness.

Proving membership of an element in an accumulator requires revealing the value of the element, and a witness.

The witness or co-factor, is the product of all the values in the accumulator except the value we are proving inclusion of.

The (value, witness) pair is the proof of inclusion in the set.

What if the value is a large number and transmitting it to the verifier and the exponentiation have non negligible costs?

This is where the above NI-PoKE2 protocol comes in. Instead of sending the proof as above, we can prove knowledge of a witness which gives a valid proof! This may seem unlikely, given that our examples are simple, but we’ll see how it may happen in the batching membership proofs section below.

Proving Non-Membership

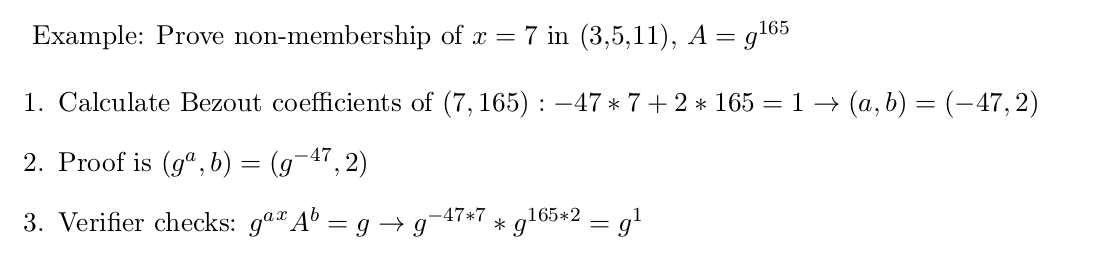

The proof of non-membership requires calculating Bezout’s Coefficients of the element we’re proving and the product of the elements in the set. An excellent guide on this topic can be found here.

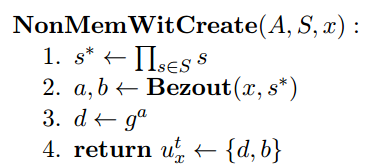

Create a non-membership witness

Verify a non-membership witness

As an example:

Proving exclusion of the value 7, in a set with {3,5,11}

Vitalik Buterin also proposes a way to prove non-membership here, which he conceived indepedently. (no proof of its security is provided, so might want to be careful if using it!)

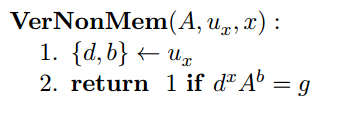

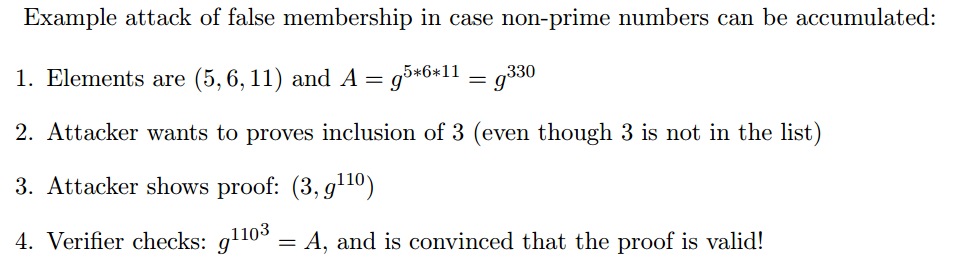

Hashing to Prime Numbers

Odd prime numbers (ie primes without 2) are required both for the Proof of Knowledge protocols, but also for the accumulator elements. If the elements accumulated are not primes, then an adversary could fool a verifier about the inclusion of an element, without the element being in the set.

Valid proof of membership for a non-accumulated element!

As a result we must restrict the accumulated elements to be primes, otherwise an adversary can prove inclusion about any of the factors of an accumulated element (in this case, prove inclusion of 3 because it is a factor of 6).

Aggregating and Batching Proofs

Recall the definitions:

- Aggregate: combining many proofs in 1 constant size proof

- Batch: verify many proofs at once rather than verifying all proofs separately

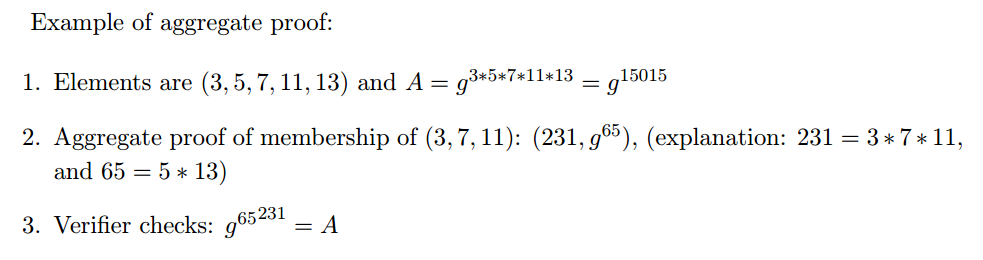

Aggregating and batching membership proofs is trivially done by multiplying the values being proven and providing a co-factor for them together:

Aggregating proofs of membership is simple!

It can be quickly seen, that if we want to create an aggregate proof of membership for a lot of elements, both the value becomes large to transmit, and the verifier needs to perform expensive exponentiations. For that, we utilize NI-PoKE2, to prove that we know the cofactor g⁶⁵, without transmitting 231 to the verifier, or the verifier computing the expensive exponentiations (we batched the verification!).

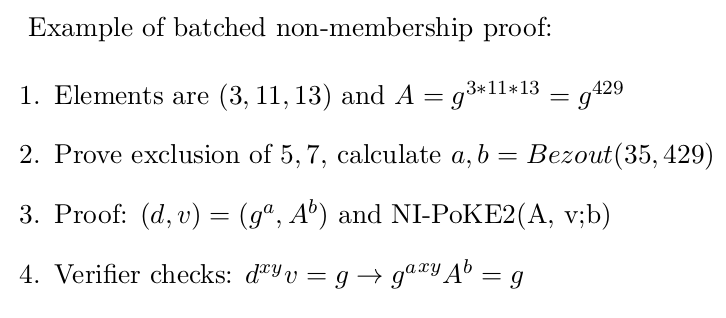

Batching non-membership proofs is done by calculating Bezout’s coefficients for the product of the elements (a’, b’), and then have the same proof as before (g^a’, b’). The size of the combined witness is approximately the same as with giving two separate witnesses.

This can be solved by instead setting the proof to be (g^a’, A^b’) . For this to be secure, the prover additionally must provide a NI-PoKE2 to prove knowledge of b' .

The NI-PoKE2 at step 3 is required for safety, otherwise an adversary could set

v = g * d^(-xy) and fool the verifier, without knowing b.

This can be made more efficient by applying a NI-PoE so that the verifier does not need to perform the exponentiation in the final step.

An efficient algorithm to aggregate non-membership proofs in a constant-size witness is not provided.

Removing the trusted setup

All exponentiations are done modulo N, which is a number with an unknown prime factorization. That is because all proofs provided are in the generic group model for groups of unknown order (Page 2), and require the Strong RSA Assumption and the Adaptive Root Assumption.

Generating a public key without knowing an associated private key is hard. As argued in page 2 of [2], it is possible to perform a secure multiparty computation to create the required number, but one would have to trust that the parties who participated in the trusted setup did not collude to retrieve the secret. Wesolowski in [2] points out an alternative via so-called “class groups”:

“A better approach would be to use the class group of an imaginary quadratic order. Indeed, one can easily generate an imaginary quadratic order by choosing a random discriminant, and when the discriminant is large enough, the order of the class group cannot be computed.”

There is currently an ongoing competition by Chia for the efficient computation of such class groups, along with a comprehensive document on the required theory behind them.

Conclusion

If you made it up to here congratulations!

We briefly described how RSA Accumulators work as well as how to construct schemes to efficiently prove membership and non-membership of elements in the accumulator. The authors additionally provide ways to construct position-binding commitments, also known as vector commitments with batched openings at various indexes, which is not a feature of merkle trees. The authors construct the first vector commitment scheme which can perform O(1) openings (opening means proving revealing the value of an element at a certain index in the commitment) and O(1) public parameters (public parameters are generated during initialization of the commitment scheme, previous constructions required linear or even quadratic parameters).

Here is a great lecture on Commitment Schemes

Use Cases

These accumulators can be used to create stateless blockchains, in which nodes do not need to store the whole state to be convinced about which blocks are valid. They can also be used to implement efficient UTXO commitments, which allow users to issue transactions without knowing the whole UTXO set. Finally, vector commitments can be used to create short Interactive-Oracle-Proofs, which require a prover and verifier to play a game where the prover tries to answer the verifier’s queries about some committed data. This process is made much more efficient than when using a Merkle Tree.

What’s next?

This was a great paper, which introduced and formalized a lot of primitives which can be used for the scalability of blockchain constructions.

In particular, the RSA Accumulator has gathered a lot of the Plasma research community’s interest, as to how it can be utilized for compaction of UTXO history in Plasma Cash. There has been a number of posts on ethresear.chlately on how this can be constructed. As a result, in the next post I’ll perform a review of the current schemes, their advantages and disadvantages, as well as which one is most likely to be used for reducing history in Plasma Cash (+variants).

I am also very interested in a non-fungible Plasma construction which may utilize Vector Commitments.

References

[1] https://eprint.iacr.org/2018/1188

313

313

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?