设计师思维 工程师思维

By Marco Ossani & Gianluca Gambatesa

Marco Ossani和Gianluca Gambatesa

为什么尽管进行了诚实的努力和对“最佳”设计思维方法的盲目应用,但大多数创新过程却失败了? 是钱吗 时间? 人? 这与流程有关吗? (Why do most of the Innovation processes, despite honest efforts and slavish application of the “best” Design Thinking approach, miserably fail? It’s about money? Time? People? Is it all about the Process?)

Since its official introduction in the industrial world and in Business Schools (thanks to many, out of which you must name Tom Kelley at IDEO) — Design Thinking (DT) aspired to be THE universal, all-fields-encompassing process to develop any design or innovation project.

小号因斯在工业界和商学院的官方介绍(感谢很多,在外面你必须命名汤姆·凯利在IDEO) -设计思维(DT)渴望成为普遍,全领域的无所不包的进程,制定任何设计或创新项目。

Nobody can honestly deny that DT has stood the test of time, at least regarding the following pillars of any product/solution development:

坦白地说,没有人可以否认DT经过了时间的考验,至少在任何产品/解决方案开发的以下Struts方面都如此:

- the central role of the users/customers and the need of observing/listening to them 用户/客户的核心角色以及对他们进行观察/收听的需求

- the importance of “prototyping” something that people can experience to gain insight on the value we’ve been able to generate. 人们可以体验的“原型”产品的重要性,以洞察我们已经产生的价值。

Nonetheless, despite its remarkable track record of successes, DT soon became subject to extreme criticism from the most disparate sources, mainly for being used as a rigid one-fits-all frame of formal blocks. Strangely enough, the critics spent more time on process and tools than on rethinking (as designers) HOW the process was implemented.

尽管如此,尽管DT取得了令人瞩目的成功,但很快就受到来自最不同来源的批评,这主要是因为DT被用作严格的“万能”正式框架。 奇怪的是,与(作为设计者)重新思考如何实施流程相比,批评者在流程和工具上花费了更多的时间。

We believe it’s time to stop forcing “non designers” to “think as designers”, and simply make them “behave like designers” — where behaving means being clearly connected to reality and context, being experiential and outside-looking.

我们认为,是时候停止强迫“非设计师”“思考设计师”,而只是使他们“像设计师一样”了-在这种情况下,行为意味着与现实和背景清晰地联系在一起,具有体验性和外观。

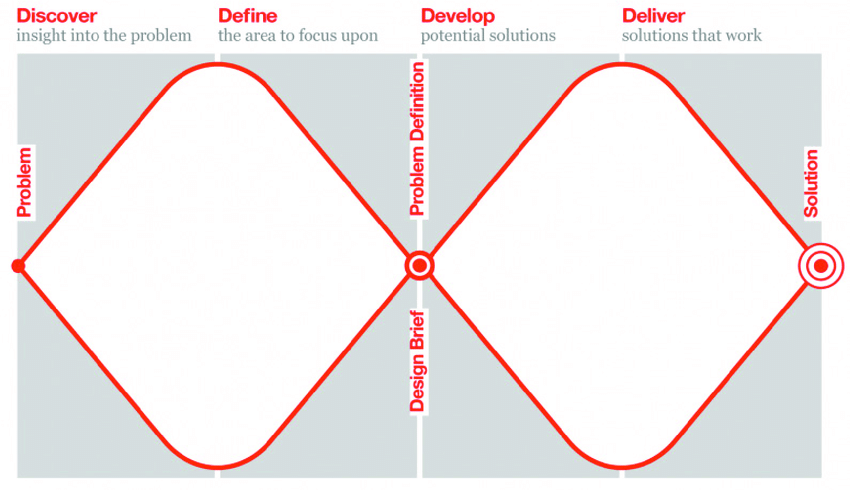

In 2004, the Design Council developed a simple and elegant visual representation of the design process, the Double Diamond (DD), drawing attention to the alternation of divergent & convergent thinking, as two necessary and totally separated moments (“if you draw at the same time cold and hot water from the tap, what you get is just lukewarm water…”) — as the graphics suggests, there’s a clear-cut separation between subsequent phases in a very simple linear array.

2004年, 设计局开发了一种简单的设计过程高雅的视觉表现, 双钻石 (DD),提请注意发散与收敛思维的交替,作为两个必要的和完全分离的时刻(“ 如果你画的同时从水龙头中取出冷热水,您得到的只是温水…… ” —如图所示,在非常简单的线性阵列中的后续阶段之间有明确的分隔。

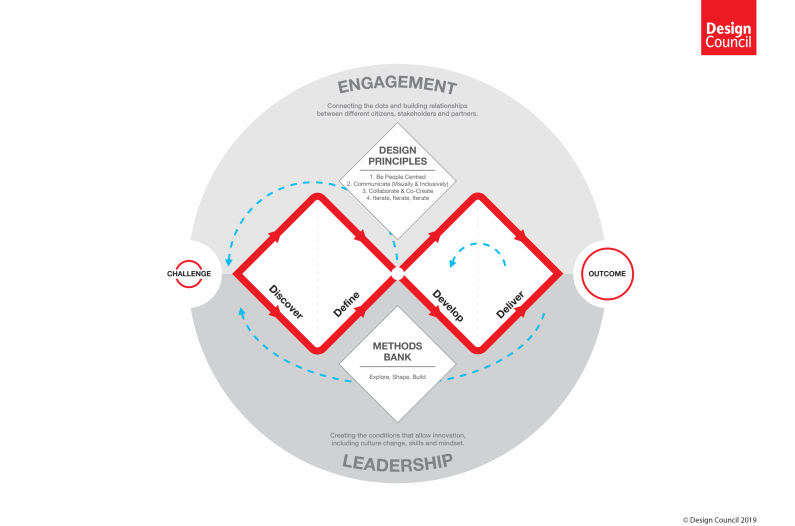

It’s remarkable that the DD has recently been re-formulated by Design Council itself, to enrich and broaden it into what they call Framework for Innovation.

值得注意的是,DD最近已由设计委员会重新制定 ,以将其丰富和扩展到他们所谓的创新框架中 。

This choice, that we strongly agree with, acknowledges the complexity underlying the process and tries to put the DD in a different and broader context — the process itself is not enough!

我们非常同意的这一选择承认了流程背后的复杂性,并试图将DD置于不同且更广泛的环境中-流程本身还不够!

The first major change is about the “linearity” of the process — the path from a challenge to an outcome must be iterative, i.e. it should naturally “flow” back and forth between different “phases” — we must be able to continuously revisit and reframe the challenge, based on the outcomes we obtain.

吨 他第一个重大变化是对过程的“ 线性 ” -从挑战到一个结果的路径必须是迭代的 ,也就是说,它自然应该“流”前后不同的“阶段”之间- 我们必须能够不断地回访并根据我们获得的成果重新设计挑战 。

We always considered this iterative, cyclical/spiral movement as a fundamental, not negotiable feature of the process — if we miss it, we miss all the power of discovery: it’s almost like starting with one nice idea we had, and simply try to make it better gathering some users’ input — very similar to asking closed questions.

我们一直将这种循环,循环/螺旋运动视为过程的基本特征,而不是可以谈判的特征–如果我们错过了它,我们将失去发现的全部力量:这就像从我们拥有的一个好主意开始,然后尝试使最好收集一些用户的输入-与询问封闭式问题非常相似。

Iterations means learning (it’s not by chance that Team Learning is one of Peter Senge’s 5 Disciplines…) — being able to incorporate new findings in a new discovery.

迭代意味着学习(团队学习不是Peter Senge的5个学科之一……)–能够将新发现整合到新发现中。

Unfortunately, DD adopters often transform a design challenge into a “Short ride in a fast machine” — not being able to go back and reframe the challenge once they get to the Develop phase. So it’s good to see this principle explicitly stated by such an authoritative source, as it was probably not clearly reflected by the linear DD visual.

不幸的是,DD采纳者经常将设计挑战转换为“ 快速骑乘机器 ”-一旦进入开发阶段就无法回头重新设计挑战。 因此,很高兴看到这种权威人士明确提出了这一原则,因为线性DD视觉效果可能无法清楚地反映出这一原则。

The second major change is the strong focus on a broader stakeholder concept, to ensure the highest people engagement in the process. Lots of Companies and Teams struggle with detachment and disconnect as they face a design challenge — a lot of proposed methods block people in defined and fixed roles, some of them highly passive or ancillary. This doesn’t elicit real participation and favours disengagement, groupthink and social loafing, with a deadly impact on learning and insights.

吨 他第二个主要的变化是重点关注更广泛的利益相关者的概念 ,以确保在这个过程中最高的人参与 。 许多公司和团队在面对设计挑战时都面临着超脱和分离的挑战-许多提议的方法阻碍了处于既定角色和固定角色的人员,其中有些人非常被动或辅助。 这不会引起真正的参与,而是会鼓励脱离接触,集体思考和社交活动,对学习和见识产生致命影响。

Again, we believe this was not at all the intent of DD proponents, but a consequence of a self-referential set of methodologies and practices aiming to just “close” a specific phase with a documented output to move on to the following…for the sake of a “sprint”.

再次,我们认为这完全不是DD支持者的意图,而是一系列自我参照的方法论和实践的结果,这些方法论和实践旨在“关闭”特定阶段,并以书面形式输出到以下内容……为了“ 冲刺 ”。

In a nutshell, we clearly see the brand new “framework for innovation” as a continuous and flowing experience of team learning through the “breath” of divergence and convergence, where everybody can experiment and share, feeling highly responsible for the process itself.

简而言之,我们清楚地看到全新的“创新框架”是团队学习通过散布和融合的“呼吸”获得的连续不断的团队学习经验,每个人都可以进行试验和分享,并对流程本身负有高度责任感。

The third major change is about putting an accent on Leadership, often expressed in terms of endorsement and support of the challenge by somebody having authority — this is true but quite trivial, as time, costs, experiments and risk-taking must be allowed, encouraged and welcome, going beyond any kind of “blame culture”.

吨 他第三个重大变化是关于把对领导的口音,经常在拥护和支持通过其授权的人的挑战来表示-这是真实的,但用处不大,时间,成本,实验和冒险必须允许,受到鼓励和欢迎,超越了任何一种“怪文化”。

However, we believe that, here, the very important reference is to the special kind of “shared leadership” we should see thriving in a really participative co-creation effort. A system can achieve real co-creation when all the stakeholders continuously follow a profound conversation, where every participant shares the responsibility for the innovation challenge.

但是,我们认为,在这里,非常重要的参考是特殊类型的“共享领导力”,我们应该看到在真正参与性的共同创造工作中取得了长足的发展。 当所有利益相关者不断进行深刻的对话时,每个参与者共同承担创新挑战的责任,系统就可以实现真正的共创。

We think that the rigid separation of convergence and divergence should be set apart, to allow deep digging into the challenge to reach valuable and multi-faceted insights. A common obstacle to this is the confusion between divergent/creative and convergent/judgemental — these are cognitive categories, not rigid phases — they look separated in a “snapshot” of the process, but the switch between the two naturally and freely happens, in both directions, as the inhale/exhale process.

我们认为,应该将趋同与分歧的僵化分开,以深入挖掘挑战,以获取有价值的,多方面的见解。 一个常见的障碍是发散性/创造性和趋同性/判断性之间的混淆- 这些是认知类别,而不是僵化阶段 -它们在过程的“快照”中看起来是分开的,但是在自然和自由之间切换是自然的两个方向,如吸气/呼气过程。

Most of the time design challenges avoid a lot of empathic discovery to jump-start with defining a “How might we?” question. In reality, when you start an innovation challenge, you never know in advance any “How might we?” question, being it the outcome of a participative effort to collect observations and give them a “meaning”. Moreover, the entire process may require, as we observe stakeholders’ experience (e.g. in the second diamond, with a prototype), to go back and change/reframe your HMW question.

大多数时候,设计挑战避免了很多同理心的发现, 而是从定义“ 我们将如何? “ 题。 实际上,当您发起创新挑战时,您永远不会事先知道“ 我们怎么可能? 问题,这是参与收集意见并赋予其“含义”的努力的结果。 而且,整个 当我们观察利益相关者的经验时(例如,在第二个菱形中,带有原型),该过程可能需要返回并更改/重新构造您的HMW问题。

The very essence of the process is aiming to keep ALL the stakeholders in a continuous, “breathing” iterative flow, either you’re discovering and defining your challenge or you’re testing a prototype — to broaden the learning and enrich and consolidate the meaning.

该过程的本质是旨在使所有利益相关者保持连续的“呼吸”式迭代流程,无论是发现和定义挑战,还是测试原型,以扩大学习范围并丰富和巩固含义。

And this clearly connect to Otto Scharmer’s concept of “co-creation” and Peter Senge’s “Team Learning”.

这显然与奥托·夏默(Otto Scharmer)的“ 共同创造 ”概念和彼得·圣吉(Peter Senge)的“ 团队学习 ”概念有关。

Now a big question arises: how might we, Design Facilitators, help design teams to apply this “framework for innovation” and achieve a completely different level of engagement, participation and shared leadership?

现在出现了一个大问题:我们的设计促进者如何才能帮助设计团队应用这种“创新框架”并实现完全不同的参与,参与和共同领导水平?

We have recently worked with a Client — Fondazione Golinelli — on the ICARO 2020 Project, and we have shared thoughts with the Project Manager — Valerio Pappalardo — who expressed his concern and frustration about some issues he and his facilitation team often faced when implementing DT to tackle design challenges with University students enrolled in Social Innovation Projects. During a long and intense conversation with us, Valerio has clearly identified most of the issues related to DT implementation: decreasing participation as the process moves forward and weak process ownership. He then agreed that the root causes of these issues could be traced back to a general lack of engagement and shared leadership.

我们最近与ICARO 2020项目的客户Fondazione Golinelli合作 ,并且与项目经理Valerio Pappalardo分享了想法, Valerio Pappalardo对他和他的促进团队在实施DT时经常遇到的一些问题表示关注和沮丧。与参加社会创新项目的大学生一起应对设计挑战。 在与我们进行的长时间紧张的交谈中,Valerio清楚地确定了与DT实施相关的大多数问题:随着流程的推进,参与度降低,流程所有权下降。 然后他同意,这些问题的根本原因可以追溯到普遍缺乏参与和共同领导。

Our proposed solution was an alternative way to reframe the DT process experience by adopting Liberating Structures to create time and space for true enriching conversations, distributing content and responsibility among all the participants. This is a key element to generate engagement and shared leadership.

我们提出的解决方案是通过采用“ 解放结构” 来创造时间和空间来真正丰富对话,在所有参与者之间分配内容和责任, 从而重塑DT过程经验的另一种方法 。 这是产生参与和共同领导的关键因素。

This doesn’t mean just adding new “methods” to our toolkit — this is not a matter of WHAT, it’s a matter of HOW. We are now in the meta-design space — the design of the design process itself. To go back to our Client example, we have adopted a flexible (multiple/iterative) application of the following LS — linked in this string:

这并不意味着只是向我们的工具箱中添加新的“ 方法 ”,这不是问题,而是问题。 我们现在处于元设计空间-设计过程本身的设计。 回到我们的“客户”示例,我们采用了以下LS的灵活(多次/迭代)应用程序-链接在此字符串中:

Appreciative Interviews: this is a very good starting point, as it sets the team’s mood on what “worked” in other contexts, more or less related to their challenge. People share success stories they’ve experienced, first in couples, then in groups of four (everyone is requested to tell the story heard from his partner) — and then they start working on what the stories have in common, to look for underlying success patterns. This is a very powerful enhancer of engagement, being based on letting the patterns to emerge from different personal stories, often set in alternative/similar contexts;

赞赏的访谈 :这是一个很好的起点,因为它可以使团队在其他情况下(或多或少地)与他们的挑战相关的“工作”氛围上来。 人们分享经验的成功故事 ,首先是一对夫妇,然后是四人一组(要求每个人讲述从他的伴侣那里听到的故事),然后他们开始研究故事的共同点,以寻找潜在的成功模式 。 这是一种非常强大的互动增强器,其基础是让模式出现在不同的个人故事中,而这些故事通常是设置在替代/相似的环境中;

User Experience Fishbowl (UEF): a compact and adapted version of various popular facilitation methods known as “Circle”, it allows a group of 5/6 people — directly involved in the context — sit together in a circle to shed light upon their experience during an open conversation, without interruptions to the sharing of their stories (often with a “talking stick”). This group constitutes the inner circle — all the other participants are sitting around them in the outer circle — they deeply listen and take notes in silence. It’s important that there is no direct dialogue between the two circles to ensure the outer circle generates questions on what they hear. At the end of the storytelling round, the outer circle selects the questions to bring, written on paper, to the inner circle: people decide in which order and how to answer, as a group. This helps to avoid the typical bias of many interviewers: the questions are consequences of “guessed” — instead of real/told — stories. You can easily imagine the extraordinary level of information and insights you can achieve by running multiple UEF sessions to reinforce the iteration of divergent and convergent thinking.

用户体验鱼缸(UEF) :各种流行的简化方法(称为“圈子” )的紧凑且经过改编的版本,它允许5/6人 (直接参与到上下文中)围成一圈坐在一起,以阐明他们的体验在公开对话期间,不间断地分享他们的故事 (通常使用“会说话的棍子 ”)。 这个小组构成了一个内部圈子 -所有其他参与者都坐在外部圈子周围-他们深深地倾听并默默地做笔记。 重要的是,两个圈子之间不能直接对话,以确保外部圈子对他们听到的内容产生疑问。 在讲故事的一轮结束时,外圈选择将要写在纸上的问题带到内圈:人们决定以哪个顺序和如何回答。 这有助于避免许多访调员的典型偏见:问题是“被猜测”的故事的结果,而不是真实/真实的故事。 您可以轻松地想象通过运行多个UEF会话来加强发散性和融合性思维的迭代所能获得的非凡的信息和见解。

What? Now What? So What? (aka W3): it’s one of the best ways we have followed to review experiences through stories (that are the matter of UEF) and move toward possible actions. The entire design team — split into 5/7 people groups — makes sense of what happened/they’ve seen/heard/felt and imagine a future state for it — no matter the next step is an HMW question, or a kind of exploring prototype. The value of W3 is ensuring that a clear process of sense-making smoothly brings to a clear definition of the design challenge.

什么? 怎么办? 所以呢? (又名W3):这是我们遵循的通过故事回顾经验(这是UEF的事情)并采取可能采取的行动的最佳方法之一。 整个设计团队(分为5/7人的小组)了解发生的事情/他们已经看到的/听到的/感觉到的,并为它设想一个未来的状态 -不管下一步是HMW问题,还是一种探索原型。 W3的价值在于确保清晰的决策过程能为设计挑战带来清晰的定义。

In a nutshell, you can use multiple UEF to generate data, information and feedback around a specific challenge, then turn to W3 in order to “make a point”, ensuring shared understanding and a broad perspective. You can now move forward (to the Development/Ideation of a Prototype), or decide you definitely need to go back to the Discover/Define to gather further insights.

简而言之,您可以使用多个UEF围绕特定挑战生成数据,信息和反馈,然后转向W3以“提出要点”,从而确保共识和广泛的视野。 现在,您可以前进(进入原型的开发/想法),或者确定您绝对需要返回“发现/定义”以收集更多的见解。

We have worked with a group of 40 students, enrolled in the ICARO 2020 Project — the feedback of the participants was extremely positive — everybody felt being part of the group and working in a positive and “connected” atmosphere, intense and time-boxed but never boring or exhausting. The Project Manager was impressed with the level of awareness of the challenge, and how it has been achieved in such a short time.

我们与40名学生一起工作,参加了ICARO 2020项目-参与者的反馈非常积极-每个人都感到自己是小组的一部分,并在积极和“联系”的氛围中工作,紧张而有时间限制,但永远不要感到无聊或疲惫。 项目经理对挑战的意识以及如何在如此短的时间内实现挑战印象深刻。

It goes without saying that Liberating Structures offer other powerful tools to face this challenge — for example:

不用说, 解放结构提供了其他强大的工具来应对这一挑战,例如:

Impromptu Networking: to quickly establish, at the very beginning, a set of “expectations” brought by the participants;

即兴网络 :一开始就快速建立参与者带来的一系列“期望”;

Wicked Questions: to be able to tackle typically contradictory and conflicting needs emerging from the developing phase.

邪恶的问题 :能够解决发展阶段出现的通常矛盾和冲突的需求。

It’s time to give to engagement and shared leadership the role they deserve in the design process, time for process facilitators to leverage on the surprising power of the Liberating Structures.

现在是时候让参与和共同领导在设计过程中发挥应有的作用了,是时候让过程促进者利用Liberation Structures令人惊讶的力量了。

翻译自: https://medium.com/complexity-surfers/from-design-thinking-to-design-behaving-55db1bbb0918

设计师思维 工程师思维

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?