If you had to come up with a way to represent signed integers in 32-bits, how would you do it?

One simple solution would be to use one bit to represent the sign, and the remaining 31 bits to represent the absolute value of the number. But as many intuitive solutions, this one is not very good. One problem is that adding and multiplying these integers would be somewhat tricky, because there are four cases to handle due to signs of the inputs. Another problem is that zero can be represented in two ways: as positive zero and as negative zero.

Computers use a more elegant representation of signed integers that is obviously “correct” as soon as you understand how it works.

Clock arithmetic

Before we get to the signed integer representation, we need to briefly talk about “clock arithmetic”.

Clock arithmetic is a bit different from ordinary arithmetic. On a 12-hour clock, moving 2 hours forward is equivalent to moving 14 hours forward or 10 hours backward:

![]() + 2 hours =

+ 2 hours = ![]()

![]() + 14 hours =

+ 14 hours = ![]()

![]() – 10 hours =

– 10 hours = ![]()

In the “clock arithmetic”, 2, 14 and –10 are just three different ways to write down the same number.

They are interchangeable in multiplications too:

![]() + (3 * 2) hours =

+ (3 * 2) hours = ![]()

![]() + (3 * 14) hours =

+ (3 * 14) hours = ![]()

![]() + (3 * -10) hours =

+ (3 * -10) hours = ![]()

A more formal term for “clock arithmetic” is “modular arithmetic”. In modular arithmetic, two numbers are equivalent if they leave the same non-negative remainder when divided by a particular number. Numbers 2, 14 and –10 all leave remainder of 2 when divided by 12, and so they are all “equivalent”. In math terminology, numbers 2, 14 and –10 are congruent modulo 12.

Fixed-width binary arithmetic

Internally, processors represent integers using a fixed number of bits: say 32 or 64. And, additions, subtractions and multiplications of these integers are based on modular arithmetic.

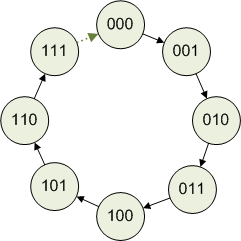

As a simplified example, let’s consider 3-bit integers, which can represent integers from 0 to 7. If you add or multiply two of these 3-bit numbers in fixed-width binary arithmetic, you’ll get the “modular arithmetic” answer:

1 + 2 –> 3

4 + 5 -> 1

The calculations wrap around, because any answer larger than 7 cannot be represented with 3 bits. The wrapped-around answer is still meaningful:

- The answer we got is congruent (i.e., equivalent) to the real answer, modulo 8

This is the modular arithmetic! The real answer was 9, but we got 1. And, both 9 and 1 leave remainder 1 when divided by 8. - The answer we got represents the lowest 3 bits of the correct answer

For 4+5, we got 001, while the correct answer is 1001.

One good way to think about this is to imagine the infinite number line:

![]()

Then, curl the number line into a circle so that 1000 overlaps the 000:

In 3-bit arithmetic, additions, subtractions and multiplications work just they do in ordinary arithmetic, except that they move along a closed ring of 8 numbers, rather than along the infinite number line. Otherwise, mostly the same rules apply: 0+a=a, 1*a=a, a+b=b+a, a*(b+c)=a*b+a*c, and so on.

Additions and multiplications modulo a power of two are convenient to implement in hardware. An adder that computes c = a + b for 3-bit integers can be implemented like this:

c0 = (a0 XOR b0) c1 = (a1 XOR b1) XOR (a0 AND b0) c2 = (a2 XOR b2) XOR ((a1 AND b1) OR ((a1 XOR b1) AND (a0 AND b0)))

Binary arithmetic and signs

Now comes the cool part: the adder for unsigned integers can be used for signed integers too, exactly as it is! Similarly, a multiplier for unsigned integers works for signed integers too. (Division needs to be handled separately, though.)

Recall that the adder I showed works in modular arithmetic. The adder represents integers as 3-bit values from 000 to 111. You can interpret those eight values as signed or unsigned:

| Binary | Unsigned value | Signed value |

| 000 | 0 | 0 |

| 001 | 1 | 1 |

| 010 | 2 | 2 |

| 011 | 3 | 3 |

| 100 | 4 | -4 |

| 101 | 5 | -3 |

| 110 | 6 | -2 |

| 111 | 7 | -1 |

Notice that the signed value and the unsigned value are congruent modulo 8, and so equivalent as far as the adder is concerned. For example, 101 means either 5 or –3. On a ring of size 8, moving 5 numbers forward is equivalent to moving 3 numbers backwards.

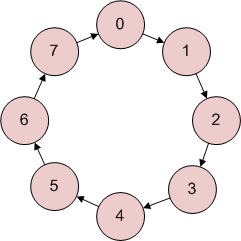

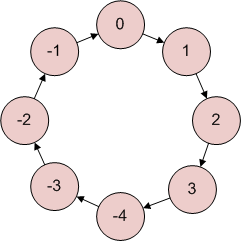

The 3-bit adder and multiplier work in the 3-bit binary arithmetic, not in ‘actual’ integers. It is up to you whether you interpret their inputs and outputs as unsigned integers (the left ring), or as signed integers (the right ring):

(Of course, you could also decide that the eight values should represent say [0, 1, –6, –5, –4, –3, –2, -1].)

Let’s take a look at an example. In unsigned 3-bit integers, we can compute the following:

6 + 7 –> 5

In signed 3-bit integers, the computation comes out like this:

(-2) + (-1) –> -3

In 3-bit arithmetic, the computation is the same in both the signed and the unsigned case:

110 + 111 –> 101

Two’s complement

The representation of signed integers that I showed above is the representation used by modern processors. It is called “two’s complement” because to negate an integer, you subtract it from 2N. For example, to get the representation of –2 in 3-bit arithmetic, you can compute 8 – 2 = 6, and so –2 is represented in two’s complement as 6 in binary: 110.

This is another way to compute two’s complement, which is easier to imagine implemented in hardware:

- Start with a binary representation of the number you need to negate

- Flip all bits

- Add one

The reason why this works is that flipping bits is equivalent to subtracting the number from (2N – 1). We actually need to subtract the number from 2N, and step 3 compensates for that – 1.

Modern processors and two’s complement

Today’s processors represent signed integers using two’s complement.

To see that, you can compare the x86 assembly emitted by a compiler for signed and unsigned integers. Here is a C# program that multiplies two signed integers:

int a = int.Parse(Console.ReadLine()); int b = int.Parse(Console.ReadLine()); Console.WriteLine(a * b);

The JIT compiler will use the IMUL instruction to compute a * b:

0000004f call 79084EA0 00000054 mov ecx,eax 00000056 imul esi,edi 00000059 mov edx,esi 0000005b mov eax,dword ptr [ecx]

For comparison, I can change the program to use unsigned integers (uint):

uint a = uint.Parse(Console.ReadLine()); uint b = uint.Parse(Console.ReadLine()); Console.WriteLine(a * b);

The JIT compiler will still use the IMUL instruction to compute a * b:

0000004f call 79084EA0 00000054 mov ecx,eax 00000056 imul esi,edi 00000059 mov edx,esi 0000005b mov eax,dword ptr [ecx]

The IMUL instruction does not know whether its arguments are signed or unsigned, and it can still multiply them correctly!

If you do look up IMUL instruction (say in the Intel Reference Manual), you’ll find that IMUL is the instruction for signed multiplication. And, there is another instruction for unsigned multiplication, MUL. How can there be separate instructions for signed and unsigned multiplications, now that I spent so much time arguing that the two kinds of multiplications are the same?

It turns out that there is actually a small difference between signed and unsigned multiplication: detection of overflow. In 3-bit arithmetic, the multiplication –1 * –2 -> 2 produces the correct answer. But, the equivalent unsigned multiplication 7 * 6 –> 2 produces an answer that is only correct in modular arithmetic, not “actually” correct.

So, MUL and IMUL behave the same way, except for their effect on the overflow processor flag. If your program does not check for overflow (and C# does not, by default) the instructions can be used interchangeably.

Wrapping up

Hopefully this article helps you understand how are signed integers represented inside the computer. With this knowledge under your belt, various behaviors of integers should be easier to understand.

(本文转自http://igoro.com/archive/why-computers-represent-signed-integers-using-twos-complement/)

111

111

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?