I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the ways in which my teaching practices might be reinforcing White supremacy.

最近,我一直在思考我的教学实践可能如何加强白人至上的思想。

In particular, I’ve been thinking about how graphic design advice that I share in my classes — advice that I thought to be “neutral” and “benign” — may serve to exclude and oppress BIPOC students.

特别是,我一直在考虑我在课堂上分享的图形设计建议(我认为是“中性”和“良性”的建议)如何排除和压制BIPOC学生。

These thoughts came to the foreground a few weeks ago. At a webinar organized by Chris Rudd at the IIT Institute of Design (“The Future Must be Different from the Past: Embracing an Anti-Racist Agenda”), graphic designer Cheryl D. Miller was asked to reflect about the elements of contemporary graphic design that she believes symbolize racism and oppression.

这些想法在几周前就成为人们关注的焦点。 在IIT设计学院的克里斯·陆克文 ( Chris Rudd)举办的网络研讨会上(“ 未来必须与过去不同:拥抱反种族主义议程 ”),平面设计师Cheryl D. Miller被要求反思当代平面设计的要素她认为象征着种族主义和压迫。

The host asked, “What is the rebel flag or Confederate monument of design, to you?” Here is what she said:

主持人问:“反叛的旗帜或同盟国的设计纪念碑对你来说是什么?” 她说的是 :

“I would like to retire the Paul Rand look. I would like to retire mid-century Helvetica. I want to retire flush left. I want to retire rag right. I want to retire white space. I want to retire the Swiss grid… It is the look of my oppressor… a mid-century era when it wasn’t easy to enter the NY marketplace as a Black designer. When I see that look, the only thing it says to me is, ‘You cannot enter. You don’t belong. You’re not good enough.’”

“我想退休保罗·兰德的样子。 我想退休本世纪中叶的Helvetica。 我想退休同花顺。 我想退休抹布吧。 我想退休空白。 我想退休瑞士的网格……这是我的压迫者的面貌……一个世纪中期,当黑人设计师进入纽约市场并不容易。 当我看到这种外观时,它对我说的唯一一句话是:“您无法进入。 你不属于 你不够好。

I recognized in Ms. Miller’s list almost everything that I’ve been telling my students is “good” design. “Use simple fonts like Helvetica,” I often say, “because they are really easy to read.” “Line things up and use a grid, because that will make your slides/posters look organized and not sloppy.” “Make sure to leave plenty of white space on the page, to give your viewers’ eyes a chance to breathe.” As a White design educator, I’m embarrassed to admit that it had never occurred to me just how much this advice can exclude and invalidate the identities of some of my students.

我在米勒女士的名单中认识到,我一直告诉我的学生的几乎所有东西都是“好”设计。 我经常说:“使用像Helvetica这样的简单字体,因为它们确实很容易阅读。” “将事情排成一行并使用网格,因为这将使您的幻灯片/海报看起来井井有条,而不是草率。” “请确保在页面上留出足够的空白,以使观众的眼睛有呼吸的机会。” 作为一名怀特设计教育者,我很尴尬地承认,我从来没有想过这种建议能在多大程度上排除和使某些学生的身份失效。

Ms. Miller was kind enough to hop on a Zoom with me to talk more about this problem, and about what design educators like me can do better, in order to dismantle White supremacy in the classroom and create a space for all of our students to flourish.

米勒女士非常友善,希望与我一起进行“缩放”讨论更多有关此问题,以及像我这样的设计教育者可以做得更好的事情,以消除教室中的白人至上主义,并为我们所有的学生创造一个空间繁荣。

这是我谈话中的四个收获。 (Here are four of my takeaways from our conversation.)

Unless otherwise noted, all block quotes below are from Ms. Miller.

除非另有说明,否则以下所有方框引号均来自米勒女士。

我必须用各种图像来充实我的视觉体验 (I have to saturate my visual experience with diverse images)

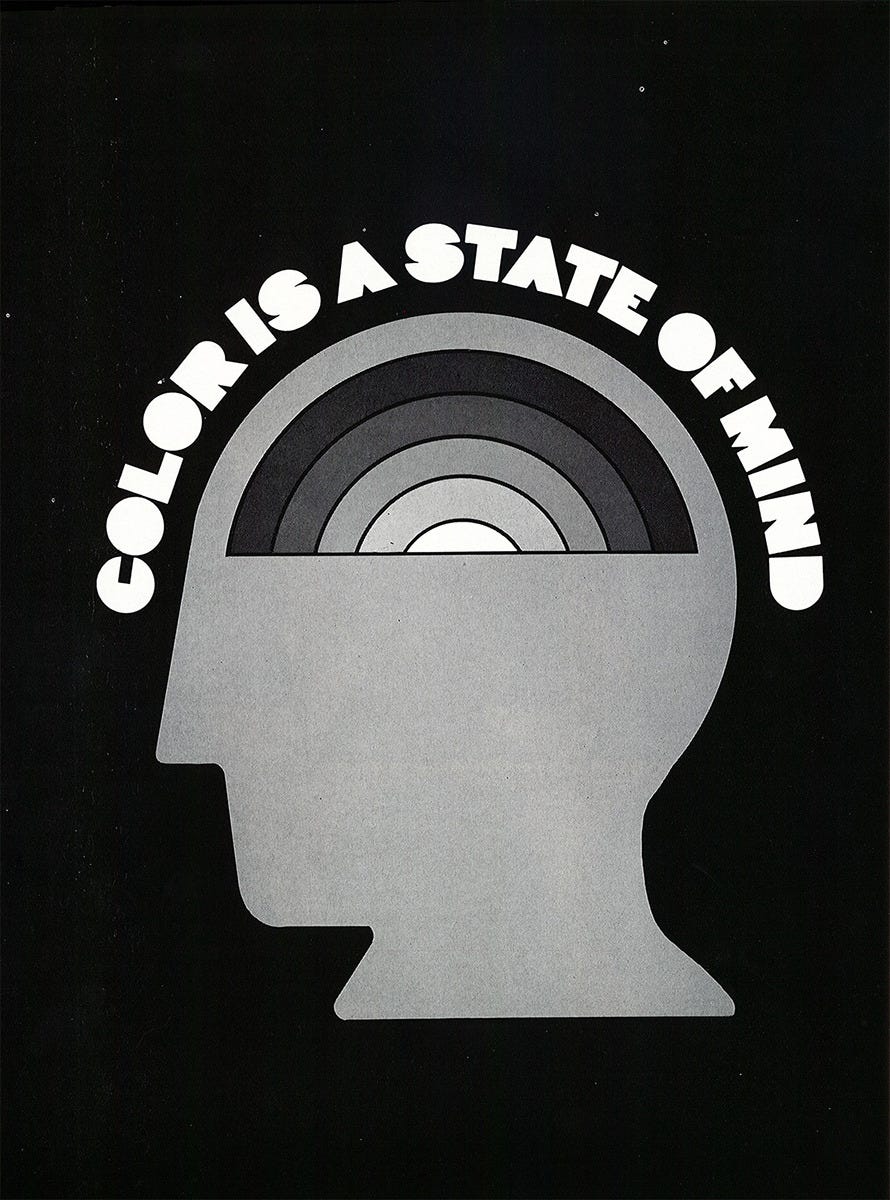

Our brains tend to equate the familiar with the good. So if all you see is work by White designers, then that’s what calibrates your taste of what constitutes “good” design. Consider: if your whole life you only listened to music by Mozart and Vivaldi, what would you think the first time you heard a song by Lizzo or Metallica? Your brain might not even code it as “music.”

我们的大脑倾向于将熟悉的事物等同于良好的事物。 因此,如果您看到的只是White设计师的作品,那么这就是您对构成“良好”设计的品味的校准。 想一想:如果您一生只听过莫扎特和维瓦尔第的音乐,那么您第一次听到利佐(Lizzo)或金属乐队(Metallica)的歌曲会如何? 您的大脑甚至可能不会将其编码为“音乐”。

A great way to make sure I’m not falling into this trap is to intentionally seek out work by BIPOC designers and add it to my mental/visual rolodex. That way, my intuition and my taste can grow and mature, and I can still develop a sense of what’s good and what’s bad, but this sense can become divorced from a White-centric aesthetic.

确保我不陷入陷阱的一种好方法是有意地寻找BIPOC设计师的作品,并将其添加到我的心理/视觉rolodex中。 这样,我的直觉和品味就可以成长和成熟,我仍然可以发展出对善与恶的感觉,但是这种感觉可能会与以白人为中心的美学脱节。

“Create your own rules for yourself, set your own standards. And that has everything to do with what you really like. So when you see something, and it responds to you, and it doesn’t fit the rules that we’ve been indoctrinated with, give it a chance.”

“为自己创建自己的规则,设置自己的标准。 这与您真正喜欢的一切有关。 因此,当您看到某些东西时,它会对您做出React,并且不符合我们所灌输的规则,那就给它一个机会。”

For some, like artist and designer Purin Phanichphant, this kind of saturation can be literal and physical: he covers his walls with images he loves, and deliberately curates this collection for diversity. Whether or not I build such a wall of inspiration, I know I can do a better job of intentionally seeking out and looking at the work of non-White designers. (And, once I’ve curated a broader visual experience, I can explicitly try to notice the ways in which these objects and images break stereotypes with which I’m familiar, and learn to appreciate the richness of this difference.)

对于某些艺术家和设计师Purin Phanichphant而言 ,这种饱和度可以是字面意义上的和物理上的:他用自己喜欢的图像遮盖了墙壁,并精心策划了该系列的多样性。 无论我是否建立起这样的灵感墙,我都知道我可以做得更好,有意识地寻找并观察非白人设计师的作品。 (而且,一旦获得了广泛的视觉体验,我就可以明确地尝试注意到这些对象和图像打破我所熟悉的刻板印象的方式,并学会欣赏这种差异的丰富性。)

The trouble is that Black designers’ work hasn’t historically been highlighted/credited, so it may be tougher to find.

问题在于,黑人设计师的工作历来没有得到强调/认可,因此可能很难找到。

But there is help. Wonderful resources like this database of BIPOC creatives and this list of Black designers are being compiled and shared. The recent Where Are The Black Designers? conference — organized by Mitzi Okou — and the Slack community that grew out of it, are providing White design educators a kind of access to this community that effectively removes my excuses for keeping my head in the sand, because “examples of Black designers are hard to find.”

但是有帮助。 诸如BIPOC创意数据库和黑人设计师列表之类的精彩资源正在被编译和共享。 最近黑人设计师在哪里? 由Mitzi Okou举办的会议和由此产生的Slack社区 ,为White设计教育者提供了进入该社区的一种方式,有效地消除了我束手无策的借口,因为“黑人设计师的榜样很难找到。”

“Stop asking ‘Where are the Black designers?’ We’re right here! The question is: Where have you all been?”

“别问'黑人设计师在哪里?' 我们就在这里! 问题是:你们都去哪里了?”

我必须学习和教导历史-整个历史 (I have to learn and teach the history — the whole history)

You’re probably familiar with the work and name of Milton Glaser, the iconic mid-century White graphic designer who created the I ❤ NY logo. But you’re probably less familiar with the work and name of Black graphic designer Reynold Ruffins, Glaser’s long-time partner and collaborator, with whom Glaser co-founded Push Pin Studios in 1954. Ruffins’ work was no less far-reaching and prominent than Glaser’s: his clients included IBM, AT&T, Coca-Cola, CBS, Pfizer, The New York Times, Fortune, and the U.S. Postal Service. But White supremacy means erasure of Black voices, so you didn’t learn about him in your classes. It’s not your fault. But you can do better now.

您可能熟悉Milton Glaser的工作和名字,Milton Glaser是本世纪中叶的白色图形设计师,创建了I❤NY标志。 但是,您可能不太熟悉黑人图形设计师雷诺·鲁芬斯(Reynold Ruffins)的工作和名字,格拉瑟是长期的合伙人和合作者,格拉瑟在1954年与格拉瑟共同创立了图钉工作室 。鲁芬斯的工作同样具有深远的影响力和杰出的地位。比Glaser的客户高:他的客户包括IBM,AT&T,可口可乐,CBS,辉瑞, 《纽约时报》 , 《财富》和美国邮政服务。 但是,白人至上意味着消除黑人的声音,因此您在上课时没有了解他。 这不是你的错。 但是您现在可以做得更好。

A study of history is important not only because it allows us to avoid repeating past mistakes, but also because it allows us to build on past successes. A failure to recognize, appreciate, and build upon the best work of all designers who came before us is a disservice to humanity, present and future.

对历史的研究很重要,不仅因为它使我们避免重复过去的错误,而且因为它使我们能够基于过去的成功。 未能认识到,欣赏并建立在我们之前的所有设计师的最佳作品之上, 这对人类,现在和未来都是有害的。

And a study of history is not (and can’t be) neutral: it is a series of stories told by people — people with biases and agendas. This means that an anti-racist design classroom has to explicitly embrace an anti-racist historical narrative.

而且对历史的研究不是(也不能是中立的):这是一系列由人们讲述的故事,这些故事的人带有偏见和议程。 这意味着反种族主义的设计教室必须明确地包含反种族主义的历史叙述。

“I studied art history right there with you. I went to RISD. I went to Pratt. I went to MICA. What art history did I learn? Your art history. What design did I learn? Your design. You learned nothing of mine.”

“我在那里与您一起学习艺术史。 我去了RISD。 我去了普拉特。 我去了云母。 我学了什么艺术史? 您的艺术史。 我学了什么设计? 您的设计。 你没有学到我的东西。”

Importantly, it’s not only the case that Western education has celebrated the contributions of White designers while ignoring the contributions of Black designers. The systematic theft and erasure of Black labor and Black talent has led to a denial of Black designers ever having made any contributions in the first place. Western graphic design education doesn’t, for example, often remember that the very founders of the field of graphic design were Black:

重要的是,不仅仅是西方教育在庆祝白人设计师的贡献而忽略黑人设计师的贡献的情况。 黑人劳动者和黑人人才的系统性盗窃和根除导致黑人设计师曾经做出过任何贡献都遭到拒绝。 例如,西方的平面设计教育常常不记得平面设计领域的创始人是黑人:

“The first graphic design was Egyptian hieroglyphics, and last I checked, Egypt was in Africa. So when we talk about the history of graphic design, we’re talking about Black graphic design.”

“第一个图形设计是埃及象形文字,最后我检查了一下,埃及在非洲。 因此,当我们谈论图形设计的历史时,我们在谈论的是黑色图形设计。”

A lot of the design history that I’ve been taught is actually Black design history — appropriated, misattributed, and rebranded. And I have to acknowledge this explicitly in the classroom.

我曾经教过的许多设计历史实际上都是黑人设计历史-被盗用,错误分配和重新命名。 我必须在教室里明确承认这一点。

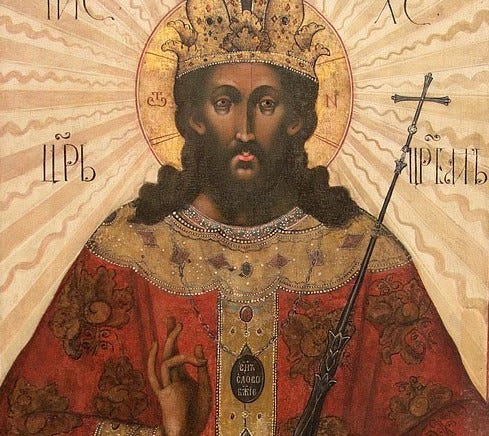

“Who painted Christ first? And what color was he painted? Have you looked carefully at 12th century Russian Orthodox depictions of Christ? Who saw Jesus, who documented him first, and who taught the Russians how to paint their churches? The Byzantines did. You want to see Black Jesus and Moses and everybody else? Look at the 12th century Orthodox churches. And then, all of a sudden, with the beginning of the Renaissance, Jesus becomes White, and that’s all you want to look at.”

“谁先画了基督? 他画的是什么颜色? 您是否仔细看过12世纪俄罗斯东正教对基督的描绘? 谁看见了耶稣,谁首先记录了他,谁教俄国人如何给教会粉刷油漆? 拜占庭人做到了。 您想看到黑人耶稣和摩西以及其他所有人吗? 看看12世纪的东正教教堂。 然后,突然之间,随着文艺复兴的开始,耶稣变成了白人,这就是你想要看的。”

The dominant Western narrative of design history has been constructed by White educators, while Black designers’ work has been hidden away from the spotlight. So how do you find that work if you’re an educator who wants to see it and show it to your students?

西方设计史上占主导地位的叙述是由白人教育者构建的,而黑人设计师的作品则被隐藏在聚光灯下。 那么,如果您是一个想要看到它并将其展示给您的学生的教育家,您如何找到它呢?

“The problem is when you start to Google, you discover that most history is not Googleable. Most archives of Black graphic designers are in card catalogs, pre-2000.”

“问题是,当您开始使用Google时,会发现大多数历史记录不可用于Google。 大部分Black图形设计师的档案都在2000年以前的卡片目录中。”

But there’s some great news. Ms. Miller has begun curating a historical database in collaboration with librarians at Stanford University, called “The History of Black Graphic Design.” 40 Black graphic designers and Ms. Miller’s colleagues are contributors to the collection, as well as the estate of Dorothy E. Hayes. As of the time of this writing, as far as I can tell, Stanford Libraries haven’t yet created a publicly searchable interface for this collection, but we can all look forward to its impending release.

但是有个好消息。 米勒女士已经开始与斯坦福大学的图书馆员合作,建立一个历史数据库,称为“黑色图形设计的历史”。 40位黑人平面设计师和Miller女士的同事为该系列以及Dorothy E. Hayes的庄园做出了贡献。 据我所知,截至撰写本文时,斯坦福图书馆尚未为该馆藏创建可公开搜索的界面,但我们都期待着即将发布的界面。

Meanwhile, other resources are being created and shared, like this 134-page (and growing) bibliography called Decentering Whiteness in Design History. The sheer volume of entries cited in the document is clear proof that the resources I need in order to learn and teach a more complete history of design are plentiful and available.

同时,正在创建和共享其他资源,例如134页(且正在不断增长)的参考书目,称为“ 设计历史中的偏心白度” 。 该文档中引用的条目数量之多清楚地证明了我为学习和教授更完整的设计历史所需的资源是充足且可用的。

Perhaps most direct and exciting is the fact that Ms. Miller herself has just developed a series of lectures on Black graphic design history, and has offered to deliver these remotely at any college or university interested in hosting them. This gives me an action item that’s almost too easy, and I’m now working on arranging for my college to host Ms. Miller for a lecture.

也许最直接和令人兴奋的事实是,米勒女士本人刚刚开发了一系列有关黑色图形设计历史的讲座 ,并愿意在有兴趣托管这些讲座的任何学院或大学中远程提供这些讲座 。 这给了我一个几乎太简单的动作项目,我现在正在努力安排我的大学主办米勒女士的讲座。

In conjunction with asking Ms. Miller to speak to my students, I have to explicitly acknowledge the historical erasure and appropriation of Black voices in design. And then I have to keep making sure that the examples of design — both historical and contemporary — that I show in my classes deliberately steer away from the all-too-White lineup that I am guilty of showcasing.

与要求Miller女士对我的学生讲话的同时,我必须明确承认在设计中对Black声音的历史抹除和挪用。 然后,我必须继续确保在课堂上展示的设计实例(包括历史和当代设计)有意避免偏离我有罪的全白系列。

“If you just serve the whole menu, then your students will appreciate it in their own way. There’s no way you can ever sit in our seat, but if you show us the whole world through design, then we will find ourselves in it.”

“如果您只提供整个菜单,那么您的学生将以自己的方式欣赏它。 您永远无法坐在我们的座位上,但是如果您通过设计向我们展示整个世界,那么我们将发现自己在其中。”

在此旅程中,我必须依靠学生作为合作者 (I have to lean on my students as collaborators in this journey)

An important truth that I already know is: my students are not there to be passive recipients of my wisdom and knowledge. I have to make them real collaborators in this effort — I have to make them learn with me, and make them help me (and each other) see better.

我已经知道的一个重要真理是:我的学生不会成为我的智慧和知识的被动接受者。 我必须使他们成为真正的合作者-我必须使他们与我一起学习,并让他们帮助我(和彼此)看到更好的事物。

Ms. Miller offered this idea for an exercise I can try with my students:

米勒女士提出了这个想法,供我与学生一起尝试的练习:

“If I were teaching a visual communications class, here’s what I would have students do.

“如果我要教视觉传达课,这就是我要做的。

Take a brand — say, McDonald’s, or Coca-Cola, or Disney — and study what it looks like in four different points on the globe. Look at Coke packaging in Brazil, and in Asia, and in North America, and in Paris. And let’s talk about what we see.

以一个品牌(例如麦当劳,可口可乐或迪斯尼)为例,研究其在全球四个不同方面的形象。 看一下巴西,亚洲,北美,巴黎的可乐包装。 让我们谈谈我们所看到的。

You’ll see that McDonald’s in Croatia looks a whole lot different than McDonald’s in New York City.

您会发现克罗地亚的麦当劳看上去与纽约市的麦当劳大不相同。

And break it down. Have the students analyze all the elements. What are the colors? What’s the typography? What’s in the restaurant? What are the furnishings? What’s in the parking lot? What’s the signage?

并分解。 让学生分析所有要素。 什么颜色 什么是版式? 餐厅里有什么? 家具是什么? 停车场里有什么? 什么是标牌?

I even suggest going to the corner grocery and convenience stores in Black, Latinx or Asian neighborhoods and look at the food packaging. Chips, drinks, canned vegetables and frozen food packaging can reveal a lot about design ethnicities! Colors, shapes and forms in the corner grocery can educate us in new ways! Just visit the corner neighborhood store!

我什至建议去黑,拉丁或亚洲社区的杂货店和便利店逛街,看看食品包装。 薯片,饮料,蔬菜罐头和冷冻食品包装可以揭示很多有关设计种族的信息! 杂货店里的颜色,形状和形式可以用新的方式来教育我们! 只需逛街角附近的商店!

You’ll start to decolonize your students’ point of view — and your own — if you have them do this kind of documentation. Look, you don’t have the answers yourself. So, get them busy!”

如果您让学生做这种类型的文档,那么您将开始非殖民化您和学生的观点。 看,你自己没有答案。 所以,让他们忙吧!”

Understanding starts with looking, so if I ask my students to look more broadly and more deeply, their understanding of design — and mine — will grow accordingly.

了解是从外观开始的,因此,如果我要求学生们更广泛,更深入地看待它们,那么他们对设计以及我的设计的理解就会相应地增长。

It’s easy to fall into the trap of feeling like I’m solely on the hook for showing design examples that can completely convey all the necessary course content and principles, and it’s easy to forget that it might be way more interesting, way more fun, and way more anti-racist, to require my students to contribute to curating our collective visual experience. I should do more of that.

很容易陷入一种感觉的陷阱,就像我只想展示可以完全传达所有必要课程内容和原理的设计示例一样,并且容易忘记它可能会更有趣,更有趣,并且要求更多的反种族主义者,要求我的学生为策划我们的集体视觉体验做出贡献。 我应该做更多的事情。

And after students have gotten some practice at this kind of multicultural analysis and appreciation, the next step can be a design exercise. I can assign a prompt along the lines of “Create a [product / brand / poster / etc.] for [insert country here].” I can ask them to design an album cover, or a beer bottle, or a restaurant menu, and to produce several variations of it, for several different points on the globe.

在学生对这种多元文化的分析和欣赏进行了一些练习之后,下一步就是设计练习。 我可以按照“在[在此处插入国家/地区]创建[产品/品牌/海报/等]”的行分配提示。 我可以请他们设计专辑封面,啤酒瓶或餐厅菜单,并为全球的几个不同点制作一些变体。

This way, I can give my students an opportunity to practice speaking multiple design languages, and develop a felt sense of how identity can shape design — and an understanding that many different identities can shape many different (equally valid) design expressions.

这样,我可以给我的学生一个练习说多种设计语言的机会,并使人们对身份如何塑造设计产生一种感觉,并理解许多不同的身份可以塑造许多不同的(同样有效的)设计表达。

我必须给我的学生捍卫他们的工作的机会和责任 (I have to give my students the opportunity and responsibility of defending their work)

A mantra that I picked up at the Stanford d.school — and which I now pass onto my students — is: “Feedback is a gift. Be nice, but be honest.” You’re not doing anyone any favors by failing to point out a critical flaw in their work. This resonated with Ms. Miller’s advice:

我在斯坦福大学医学院获得的口头禅,现在传给我的学生,是:“反馈是礼物。 很好,但要诚实。” 您没有通过指出他们的工作中的关键缺陷而对任何人都没有任何帮助。 米勒女士的建议引起了共鸣:

“The worst thing you can do is say, ‘Oh, that’s awesome.’ Give the work a crit — a real crit.”

“您能做的最糟糕的事情是说,'哦,太棒了。' 给作品一个暴击-一个真正的暴击。

As a White design educator who’s doing their best to respect students’ identities, I have on occasion stumbled into this kind of dilemma: “I don’t think this student’s work is very good. But how do I know that my opinion is not just my White supremacy showing itself? How do I know that my eyes don’t misjudge the student’s work simply because this work does not look and feel like the White-centric design aesthetic with which I’m most familiar? If I tell them their poster doesn’t look very sophisticated, am I just being racist?”

作为一名尽最大努力尊重学生身份的白人设计教育家,我有时会陷入这种困境:“我认为这名学生的工作不是很好。 但是我怎么知道我的观点不只是我的白人至高无上? 我怎么知道我的眼睛不会仅仅因为这件作品看起来和感觉不像我最熟悉的以白色为中心的设计美学而误判了学生的作品? 如果我告诉他们他们的海报看起来不是很老套,我就是种族主义者吗?”

“Sometimes it’s so hard for White instructors when they see work by students of color, and they don’t know what to say. Students put up their work and it has their identity and their culture in it, and White instructors don’t know what to do with it. Something is throwing them off: it’s not on the grid, or there’s something about the imagery, and you say ‘Oh, that’s nice,’ or you just go around it and don’t give it a crit at all.”

“有时候,当白人教员看到有色学生的作品时,他们很难受,他们不知道该说些什么。 学生们展示他们的作品,并在其中体现出自己的身份和文化,而白人教员不知道该怎么做。 某种东西正在把它们扔掉:它不在网格上,或者图像上有些东西,而您说“哦,很好,”或者您只是绕开它而完全不批评它。”

The worst thing I can do is dismiss the work and not engage with it. Both skipping over it and simply saying “that’s great” are types of dismissal.

我能做的最坏的事情是辞退工作而不参与工作。 跳过它并简单地说“很棒”都是解雇的类型。

So the best thing I can do is, before providing any feedback — before telling the student what I think of the work I’m looking at — to ask the student to describe what they’ve done: ask them to explain, justify, and defend their design choices. (And, if they can, show feedback that they’ve already received about the work from a diverse group of viewers or stakeholders.) That way, I’ll know whether a text box is not aligned to an image because it’s just sloppy or careless, or if it’s not aligned because of an intentional and well-considered design decision.

因此,我能做的最好的事情是,在提供任何反馈之前-在告诉学生我对我正在看的工作的看法之前-让学生描述他们所做的工作:请他们进行解释,论证和捍卫他们的设计选择。 (并且,如果可以的话,请向各种各样的查看者或利益相关者显示他们已经收到的有关该作品的反馈。)这样,我将知道文本框是否因为图像草率或不对齐而与图像不对齐。粗心大意,或者由于有意且经过深思熟虑的设计决策而导致不一致。

“And when it’s just poor design, you’re going to have to call it. But you have to be able to give a good reason. If it’s sloppy, if they can’t get up and defend what they’ve done, then you have to call them out.”

“而当它只是糟糕的设计时,您将不得不称之为它。 但是您必须能够给出充分的理由。 如果太草率,如果他们不能站起来捍卫自己所做的事情,那么你就必须叫他们出来。”

Black designers and Black design students can make mediocre work, too. Treating them justly means giving their work an opportunity to be judged authentically.

黑人设计师和黑人设计专业的学生也可以做平庸的工作。 公正地对待他们意味着给他们的工作一个被真实判断的机会。

结论 (Conclusion)

As a White design educator, I have to recognize that the way I define “good” design is a product of what I’ve been exposed to, and the way that I’ve been taught — my design sensibility didn’t emerge in a vacuum; it emerged and was honed in a culture of systemic racism, and so it bears the marks of that systemic racism just as everything else in our culture bears the marks of that systemic racism. My understanding, practice, and teaching of design is embedded in a social/cultural context that is shaped by and built upon systemic racism.

作为一名白人设计教育者,我必须认识到,我定义“好的”设计的方式是我所接触到的东西以及我所受教的方式的产物–我的设计敏感性并没有体现在真空; 它在系统种族主义文化中出现并得到磨练,因此它带有系统种族主义的印记,就像我们文化中的其他一切都具有系统种族主义的印记一样。 我对设计的理解,实践和教学被嵌入到系统种族主义所塑造和建立的社会/文化环境中。

So what can I do about it? Two main themes emerged for me from my conversation with Cheryl D. Miller:

那我该怎么办呢? 与Cheryl D. Miller的对话为我带来了两个主要主题:

- First, I have to re-educate my design sensibilities by broadening my diet of design, and do so in a way that consciously and intentionally seeks out and seeks to overcome the kind of erasure of design by people of color that one would expect in a systemically racist society. This entails both looking through space (finding design from across the world to appreciate and to add to my visual experience), and looking through time (learning and teaching the full history). This is an ongoing, life-long endeavor, because becoming an anti-racist design educator is like becoming a “good person:” it’s not a destination you arrive at; it’s a practice — and you’re only as “good” as your most recent action. 首先,我必须通过扩大我的设计饮食来重新教育我的设计敏感性,并且这样做的目的是要有意识地,有意地寻找并试图克服人们期望在有色人种中对设计的擦除。系统种族主义社会。 这既需要浏览空间(寻找世界各地的设计以欣赏和增加我的视觉体验),也需要浏览时间(学习和讲授全部历史)。 这是一项持续的,终生的努力,因为成为一名反种族主义的设计教育者就像成为一个“好人”:这不是您要去的目的地; 这是一种做法,而您的最新行为只是“好”。

- Second, I have to check my design sensibility (in the “check your privilege” sort of way). How can I be aware of when my design sensibilities are infecting my judgment about a piece of design in a way that might be racist, and how do I deal with that? The main idea here is two sides of the same coin: I have to give the designer space and invite the designer to justify their design choices; and then I have to engage myself in evaluating the work, but do so in a way that requires me to justify the judgments that I’m making (philosophers call this an “exchange of reasons”). Given that I’m working on the ongoing task in the first bullet point above, this is how I can engage with my students’ work right now. 其次,我必须检查我的设计敏感性(以“检查您的特权”之类的方式)。 我怎么知道我的设计敏感性何时以某种种族主义的方式影响着我对某件设计的判断,我该如何处理? 这里的主要思想是同一枚硬币的两个方面:我必须给设计者足够的空间,并邀请设计者证明他们的设计选择合理; 然后我必须投入自己的精力去评估工作,但是这样做的方式要求我证明自己所做的判断是合理的(哲学家称其为“原因交换”)。 鉴于我在上面第一个要点中正在处理正在进行的任务,因此这就是我现在可以与学生的工作进行互动的方式。

None of it is easy, and all of it is worthwhile. And it’s great to know that I have collaborators in the journey: from my students who are eager to engage in this work, to iconic designers who are willing to show the way.

所有这些都不容易,所有这些都值得。 很高兴知道我在旅途中有一些合作者:从渴望从事这项工作的学生,到愿意为自己指明道路的标志性设计师。

非常感谢 (Many thanks)

First and foremost, I am tremendously grateful to Cheryl D. Miller for her generous gift of time and words of wisdom — including both sitting down with me to talk for almost two hours, as well as helping me to edit this write-up to make sure that what I wrote down reflected what she intended to convey.

首先,我非常感谢谢丽尔·米勒(Cheryl D. Miller)慷慨的时间和智慧之言-包括与我坐下来聊了将近两个小时,以及帮助我编辑这篇文章,使之成为现实。确保我写下的内容能反映出她的意图。

Huge thanks also to Rafe Steinhauer, who made some majorly helpful edits and suggestions for how to frame this article.

还要感谢Rafe Steinhauer ,他对如何构成本文进行了一些非常有用的编辑和建议。

Finally, none of these thoughts would have crystallized into anything resembling coherence if it weren’t for my long series of conversations with Kate Nolfi, who guided me through understanding my own reflections, and massively helped to organize my thinking.

最终,如果不是我与凯特·诺尔菲(Kate Nolfi)进行的长时间对话,这些想法都不会变成连贯的东西,后者引导我理解了自己的想法,并极大地帮助组织了我的思想。

Thank you!

谢谢!

进一步阅读 (Further reading)

Selected writings by Cheryl D. Miller, plus a few articles that highlight the Black experience in graphic design:

谢丽尔·米勒(Cheryl D. Miller)精选的著作,以及一些强调黑人在图形设计方面的经验的文章:

Ms. Miller’s 1985 masters thesis at Pratt Institute: “Transcending the Problems of the Black Graphic Designer to Success in the Marketplace” (Available through the Stanford University Library).

米勒女士(Miller)于1985年在普拉特学院(Pratt Institute)攻读硕士论文:“ 超越黑人图形设计师的问题在市场上取得成功 ”(可通过斯坦福大学图书馆获得)。

Ms. Miller’s 1987 article, “Black Designers: Missing in Action,” Print.

Miller女士1987年的文章,《 黑人设计师:行动中的失踪》 , 印刷版 。

Ms. Miller’s 2016 follow-up article, “Black Designers: Still Missing in Action?” Print.

Miller女士在2016年的后续文章“ 黑人设计师:行动中仍然失踪吗? ” 打印 。

Ms. Miller’s most recent article and her final piece in the trilogy: “Black Designers: Forward in Action,” Print (2020) — Forthcoming. Keep an eye out for it!

米勒女士的最新文章以及她在三部曲中的最后一篇文章:“黑人设计师:行动中的前途”, 印刷版 (2020年)—即将发行。 请注意!

The 1991 AIGA Report “Why is Graphic Design 93% White?” by Brenda Mitchell-Powell.

1991年AIGA报告“ 为什么图形设计93%是白色? ”由Brenda Mitchell-Powell撰写。

Dorothy Jackson’s 1968 article, “The Black Experience in Graphic Design,” Print.

多萝西·杰克逊(Dorothy Jackson)1968年的文章,《 图形设计中的黑色体验 》, 印刷 。

A fabulous 2020 follow-up to that 1968 article, featuring reactions from today’s leading Black designers, edited by Stephen Coles: “The Black Experience in Graphic Design: 1968 and 2020,” Print.

1968年那篇文章的2020年精彩报道,其中包括由Stephen Coles编辑的当今领先的黑人设计师的回应:“ 平面设计中的黑人经验:1968年和2020年 ”, 印刷品 。

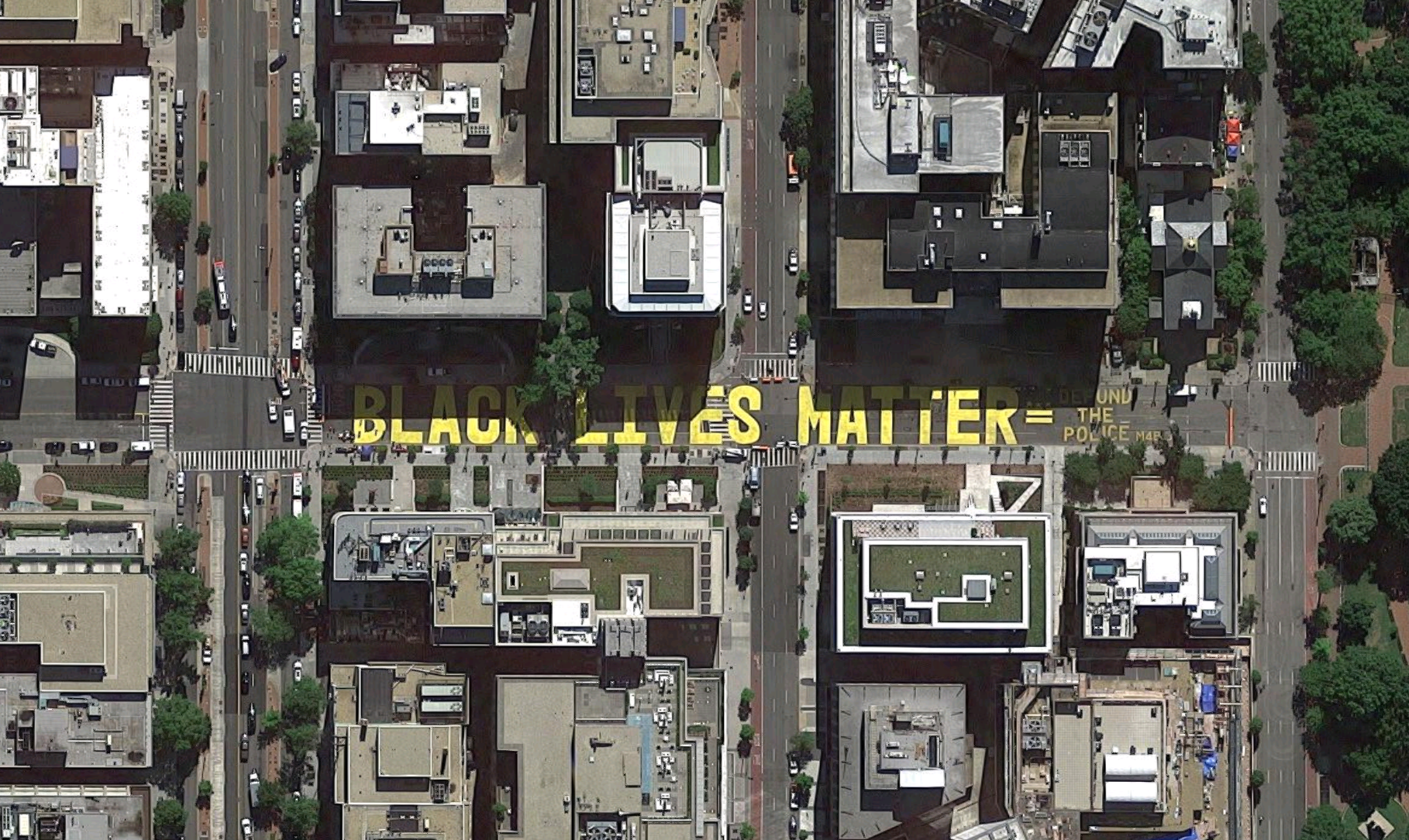

“The best Black graphic designer I know is Muriel Bowser, the mayor of Washington, DC.

“我认识的最好的黑人平面设计师是华盛顿特区市长Muriel Bowser。

She started a movement: painted ‘Black Lives Matter’ right on down the street to the White House.

她发起了一项运动:在通往白宫的大街上涂上“黑色的生活”。

You go, girl.”

你去,女孩。”

— Cheryl D. Miller

-谢丽尔·米勒

2822

2822

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?