What Is Ownership

ownership这个单词有些不好翻译,刚开始就直接叫它“ownership”即可。这里简单说一下,我对它的理解,

从“数据结构与算法”的角度来看,ownership显然不是数据,那么它就一定是数据之间的关系;在这里,它描述了变量、变量在内存(栈与堆)上的地址、复合类型的引用、简单类型的复制、变量的作用范围(生命周期)等概念以及它们之间的关系。

下面为官方描述:

All programs have to manage the way they use a computer’s memory while running. Some languages have garbage collection that constantly looks for no longer used memory as the program runs; in other languages, the programmer must explicitly allocate and free the memory. Rust uses a third approach: memory is managed through a system of ownership with a set of rules that the compiler checks at compile time. None of the ownership features slow down your program while it’s running.

Because ownership is a new concept for many programmers, it does take some time to get used to. The good news is that the more experienced you become with Rust and the rules of the ownership system, the more you’ll be able to naturally develop code that is safe and efficient. Keep at it!

栈与堆

In many programming languages, you don’t have to think about the stack and the heap very often. But in a systems programming language like Rust, whether a value is on the stack or the heap has more of an effect on how the language behaves and why you have to make certain decisions. Parts of ownership will be described in relation to the stack and the heap later in this chapter, so here is a brief explanation in preparation.

Both the stack and the heap are parts of memory that are available to your code to use at runtime, but they are structured in different ways. The stack stores values in the order it gets them and removes the values in the opposite order. This is referred to as last in, first out. Think of a stack of plates: when you add more plates, you put them on top of the pile, and when you need a plate, you take one off the top. Adding or removing plates from the middle or bottom wouldn’t work as well! Adding data is called pushing onto the stack, and removing data is called popping off the stack.

The stack is fast because of the way it accesses the data: it never has to search for a place to put new data or a place to get data from because that place is always the top. Another property that makes the stack fast is that all data on the stack must take up a known, fixed size.

Data with a size unknown at compile time or a size that might change can be stored on the heap instead. The heap is less organized: when you put data on the heap, you ask for some amount of space. The operating system finds an empty spot somewhere in the heap that is big enough, marks it as being in use, and returns a pointer, which is the address of that location. This process is called allocating on the heap, sometimes abbreviated as just “allocating.” Pushing values onto the stack is not considered allocating. Because the pointer is a known, fixed size, you can store the pointer on the stack, but when you want the actual data, you have to follow the pointer.

Think of being seated at a restaurant. When you enter, you state the number of people in your group, and the staff finds an empty table that fits everyone and leads you there. If someone in your group comes late, they can ask where you’ve been seated to find you.

Accessing data in the heap is slower than accessing data on the stack because you have to follow a pointer to get there. Contemporary processors are faster if they jump around less in memory. Continuing the analogy, consider a server at a restaurant taking orders from many tables. It’s most efficient to get all the orders at one table before moving on to the next table. Taking an order from table A, then an order from table B, then one from A again, and then one from B again would be a much slower process. By the same token, a processor can do its job better if it works on data that’s close to other data (as it is on the stack) rather than farther away (as it can be on the heap). Allocating a large amount of space on the heap can also take time.

When your code calls a function, the values passed into the function (including, potentially, pointers to data on the heap) and the function’s local variables get pushed onto the stack. When the function is over, those values get popped off the stack.

Keeping track of what parts of code are using what data on the heap, minimizing the amount of duplicate data on the heap, and cleaning up unused data on the heap so you don’t run out of space are all problems that ownership addresses. Once you understand ownership, you won’t need to think about the stack and the heap very often, but knowing that managing heap data is why ownership exists can help explain why it works the way it does.

ownership rules

As a first example of ownership, we’ll look at the scope of some variables. A scope is the range within a program for which an item is valid. Let’s say we have a variable that looks like this:

let s = "hello";

The variable s refers to a string literal, where the value of the string is hardcoded into the text of our program. The variable is valid from the point at which it’s declared until the end of the current scope. Listing 4-1 has comments annotating where the variable s is valid.

{ // s is not valid here, it’s not yet declared

let s = "hello"; // s is valid from this point forward

// do stuff with s

} // this scope is now over, and s is no longer valid

In other words, there are two important points in time here:

- When

scomes into scope, it is valid. - It remains valid until it goes out of scope.

At this point, the relationship between scopes and when variables are valid is similar to that in other programming languages. Now we’ll build on top of this understanding by introducing the Stringtype.

String类型

We’ve already seen string literals(比如"this is a string literals"), where a string value is hardcoded into our program. String literals are convenient, but they aren’t suitable for every situation in which we may want to use text. One reason is that they’re immutable. Another is that not every string value can be known when we write our code: for example, what if we want to take user input and store it? For these situations, Rust has a second string type, String. This type is allocated on the heap and as such is able to store an amount of text that is unknown to us at compile time. You can create a String from a string literal using the from function, like so:

let s = String::from("hello");

The double colon (::) is an operator that allows us to namespace this particular from function under the String type rather than using some sort of name like string_from.

let mut s = String::from("hello"); s.push_str(", world!"); // push_str() appends a literal to a String println!("{}", s); // This will print `hello, world!`

So, what’s the difference here? Why can String be mutated but literals cannot? The difference is how these two types deal with memory.

内存分配

In the case of a string literal, we know the contents at compile time, so the text is hardcoded directly into the final executable. This is why string literals are fast and efficient. But these properties only come from the string literal’s immutability. Unfortunately, we can’t put a blob of memory into the binary for each piece of text whose size is unknown at compile time and whose size might change while running the program.

With the String type, in order to support a mutable, growable piece of text, we need to allocate an amount of memory on the heap, unknown at compile time, to hold the contents. This means:

- The memory must be requested from the operating system at runtime.

- We need a way of returning this memory to the operating system when we’re done with our

String.

That first part is done by us: when we call String::from, its implementation requests the memory it needs. This is pretty much universal in programming languages. However, the second part is different. In languages with a garbage collector (GC), the GC keeps track and cleans up memory that isn’t being used anymore, and we don’t need to think about it. Without a GC, it’s our responsibility to identify when memory is no longer being used and call code to explicitly return it, just as we did to request it. Doing this correctly has historically been a difficult programming problem. If we forget, we’ll waste memory. If we do it too early, we’ll have an invalid variable. If we do it twice, that’s a bug too. We need to pair exactly one allocate with exactly one free.

Rust takes a different path: the memory is automatically returned once the variable that owns it goes out of scope

{ let s = String::from("hello"); // s is valid from this point forward // do stuff with s } // this scope is now over, and s is no // longer valid

There is a natural point at which we can return the memory our String needs to the operating system: when s goes out of scope. When a variable goes out of scope, Rust calls a special function for us. This function is called drop, and it’s where the author of String can put the code to return the memory. Rust calls drop automatically at the closing curly bracket.

Note: In C++, this pattern of deallocating resources at the end of an item’s lifetime is sometimes called Resource Acquisition Is Initialization (RAII). The drop function in Rust will be familiar to you if you’ve used RAII patterns.

This pattern has a profound impact on the way Rust code is written. It may seem simple right now, but the behavior of code can be unexpected in more complicated situations when we want to have multiple variables use the data we’ve allocated on the heap. Let’s explore some of those situations now.

Ways Variables and Data Interact:Move

简单类型

let x = 5; let y = x;

We can probably guess what this is doing: “bind the value 5 to x; then make a copy of the value in x and bind it to y.” We now have two variables, x and y, and both equal 5. This is indeed what is happening, because integers are simple values with a known, fixed size, and these two 5 values are pushed onto the stack.

字符串

let s1 = String::from("hello"); let s2 = s1;

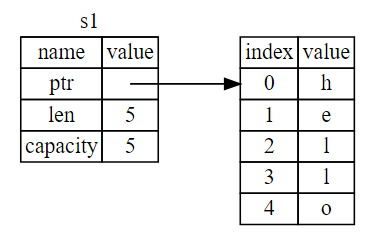

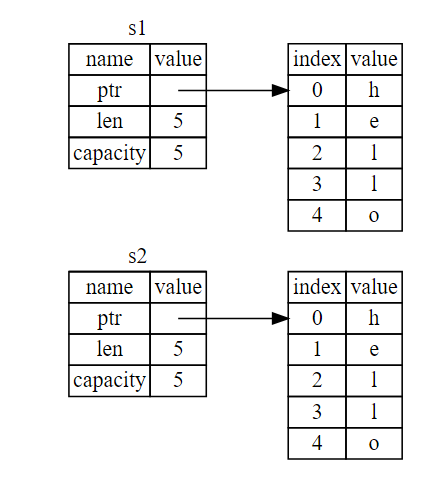

A String is made up of three parts, shown on the left: a pointer to the memory that holds the contents of the string, a length, and a capacity. This group of data is stored on the stack. On the right is the memory on the heap that holds the contents.

The length is how much memory, in bytes, the contents of the String is currently using. The capacity is the total amount of memory, in bytes, that the String has received from the operating system.

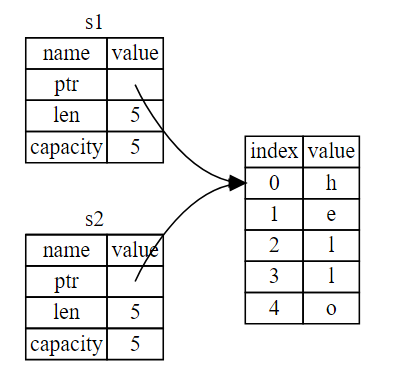

When we assign s1 to s2, the String data is copied, meaning we copy the pointer, the length, and the capacity that are on the stack. We do not copy the data on the heap that the pointer refers to.

Earlier, we said that when a variable goes out of scope, Rust automatically calls the drop function and cleans up the heap memory for that variable. This is a problem: when s2 and s1 go out of scope, they will both try to free the same memory. This is known as a double free error and is one of the memory safety bugs we mentioned previously. Freeing memory twice can lead to memory corruption, which can potentially lead to security vulnerabilities.

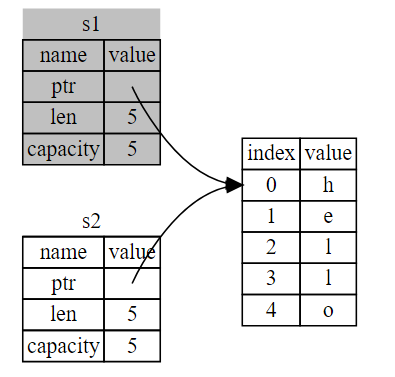

To ensure memory safety, there’s one more detail to what happens in this situation in Rust. Instead of trying to copy the allocated memory, Rust considers s1 to no longer be valid and, therefore, Rust doesn’t need to free anything when s1 goes out of scope. Check out what happens when you try to use s1 after s2 is created; it won’t work:

fn main() { let s1 = String::from("不见得繁华"); let _s2 = s1; println!("{}, 怎会明白平淡的好!", s1); }

You’ll get an error like this because Rust prevents you from using the invalidated reference

[root@itoracle ownership]# cargo run Compiling ownership v0.1.0 (/usr/local/automng/src/rust/test/ownership) error[E0382]: borrow of moved value: `s1` --> src/main.rs:5:31 | 3 | let _s2 = s1; | -- value moved here 4 | 5 | println!("{}, 怎会明白平淡的好!", s1); | ^^ value borrowed here after move | = note: move occurs because `s1` has type `std::string::String`, which does not implement the `Copy` trait error: aborting due to previous error

If you’ve heard the terms shallow copy and deep copy while working with other languages, the concept of copying the pointer, length, and capacity without copying the data probably sounds like making a shallow copy. But because Rust also invalidates the first variable, instead of being called a shallow copy, it’s known as a move.

That solves our problem! With only s2 valid, when it goes out of scope, it alone will free the memory, and we’re done.

In addition, there’s a design choice that’s implied by this: Rust will never automatically create “deep” copies of your data. Therefore, any automatic copying can be assumed to be inexpensive in terms of runtime performance.

Ways Variables and Data Interact:Clone

If we do want to deeply copy the heap data of the String, not just the stack data, we can use a common method called clone.

let s1 = String::from("hello"); let s2 = s1.clone(); println!("s1 = {}, s2 = {}", s1, s2);

Stack-Only Data:Copy

let x = 5; let y = x; println!("x = {}, y = {}", x, y);

But this code seems to contradict what we just learned: we don’t have a call to clone, but x is still valid and wasn’t moved into y.

The reason is that types such as integers that have a known size at compile time are stored entirely on the stack, so copies of the actual values are quick to make. That means there’s no reason we would want to prevent x from being valid after we create the variable y. In other words, there’s no difference between deep and shallow copying here, so calling clone wouldn’t do anything different from the usual shallow copying and we can leave it out.

So what types are Copy? You can check the documentation for the given type to be sure, but as a general rule, any group of simple scalar values can be Copy, and nothing that requires allocation or is some form of resource is Copy. Here are some of the types that are Copy:

- All the integer types, such as

u32. - The Boolean type,

bool, with valuestrueandfalse. - All the floating point types, such as

f64. - The character type,

char. - Tuples, if they only contain types that are also

Copy. For example,(i32, i32)isCopy, but(i32, String)is not.

Ownership and functions

fn main() { let s = String::from("hello"); // s comes into scope takes_ownership(s); // s's value moves into the function... // ... and so is no longer valid here let x = 5; // x comes into scope makes_copy(x); // x would move into the function, // but i32 is Copy, so it’s okay to still // use x afterward } // Here, x goes out of scope, then s. But because s's value was moved, nothing // special happens. fn takes_ownership(some_string: String) { // some_string comes into scope println!("{}", some_string); } // Here, some_string goes out of scope and `drop` is called. The backing // memory is freed. fn makes_copy(some_integer: i32) { // some_integer comes into scope println!("{}", some_integer); } // Here, some_integer goes out of scope. Nothing special happens.

If we tried to use s after the call to takes_ownership, Rust would throw a compile-time error. These static checks protect us from mistakes. Try adding code to main that uses s and x to see where you can use them and where the ownership rules prevent you from doing so.

Return Values and Scope

fn main() { let _s1 = gives_ownership(); // gives_ownership moves its return // value into s1 let _s2 = String::from("hello"); // s2 comes into scope let _s3 = takes_and_gives_back(_s2); // s2 is moved into // takes_and_gives_back, which also // moves its return value into s3 } // Here, s3 goes out of scope and is dropped. s2 goes out of scope but was // moved, so nothing happens. s1 goes out of scope and is dropped. fn gives_ownership() -> String { // gives_ownership will move its // return value into the function // that calls it let some_string = String::from("hello"); // some_string comes into scope some_string // some_string is returned and // moves out to the calling // function } // takes_and_gives_back will take a String and return one fn takes_and_gives_back(a_string: String) -> String { // a_string comes into // scope a_string // a_string is returned and moves out to the calling function }

The ownership of a variable follows the same pattern every time: assigning a value to another variable moves it. When a variable that includes data on the heap goes out of scope, the value will be cleaned up by drop unless the data has been moved to be owned by another variable.

fn main() { let s1 = String::from("hello"); let (s2, len) = calculate_length(s1); println!("The length of '{}' is {}.", s2, len); } fn calculate_length(s: String) -> (String, usize) { let length = s.len(); // len() returns the length of a String (s, length) }

[root@itoracle ownership]# cargo run Compiling ownership v0.1.0 (/usr/local/automng/src/rust/test/ownership) Finished dev [unoptimized + debuginfo] target(s) in 6.01s Running `target/debug/ownership` The length of 'hello' is 5.

1787

1787

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?