This chapter explains these aspects(方面) of the PL/SQL language:

■ Character Sets

■ Lexical Units(词法单元)

■ Declarations

■ References to Identifiers(引用标识符)

■ Scope and Visibility of Identifiers(标识符的范围和可见性)

■ Assigning Values to Variables

■ Expressions

■ Error-Reporting Functions

■ SQL Functions in PL/SQL Expressions

■ Pragmas

■ Conditional Compilation

Character Sets

Any character data to be processed by PL/SQL or stored in a database must be represented(表示) as a sequence of bytes(一个字节序列).

The byte representation of a single character is called a character code.

A set of character codes is called a character set.

Every Oracle database supports a database character set and a national character set.

PL/SQL also supports these character sets.

This document explains how PL/SQL uses the database character set and national character set.

Topics

■ Database Character Set

■ National Character Set

See Also: Oracle Database Globalization Support Guide for general information about character sets

Database Character Set

PL/SQL uses the database character set to represent:

■ Stored source text of PL/SQL units

For information about PL/SQL units, see “PL/SQL Units and Compilation Parameters” on page 1-10.

■ Character values of data types CHAR, VARCHAR2, CLOB, and LONG

For information about these data types, see “SQL Data Types” on page 3-2.

The database character set can be either single-byte, mapping each supported character to one particular byte(每个支持的字符映射到一个特定的字节), or multibyte-varying-width(多字节不同宽度), mapping each supported character to a sequence of(一系列) one, two, three, or four bytes.

The maximum number of bytes in a character code depends on the particular character set.

Every database character set includes these basic characters:

■ Latin letters(拉丁字母): A through Z and a through z

■ Decimal digits(小数位数): 0 through 9

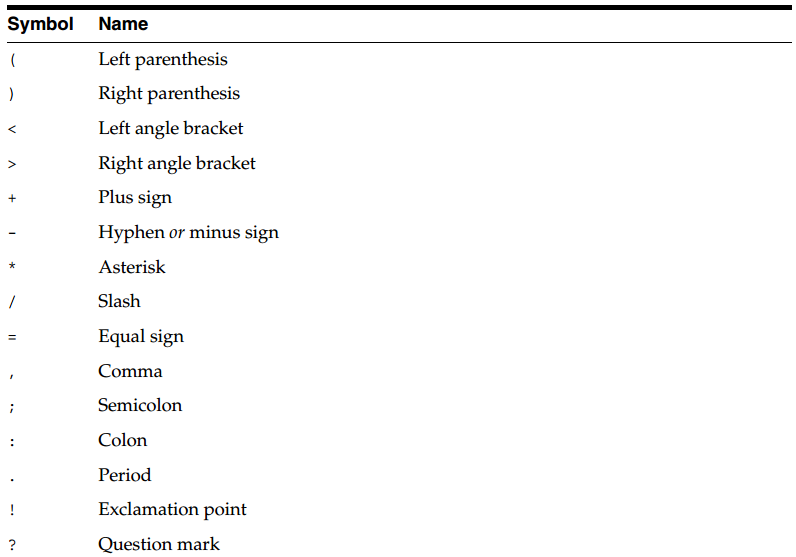

■ Punctuation characters(标定符号) in Table 2–1

■ Whitespace characters(空格字符): space, tab, new line, and carriage return(回车)

PL/SQL source text that uses only the basic characters can be stored and compiled in any database.

PL/SQL source text that uses nonbasic characters can be stored and compiled only in databases whose database character sets support those nonbasic characters.

Table 2–1 Punctuation Characters in Every Database Character Set

See Also: Oracle Database Globalization Support Guide for more information about the database character set

National Character Set

PL/SQL uses the national character set to represent character values of data types NCHAR, NVARCHAR2 and NCLOB.

For information about these data types, see “SQL Data

Types” on page 3-2.

See Also: Oracle Database Globalization Support Guide for more information about the national character set

Lexical Units

The lexical units of PL/SQL are its smallest individual(独特的) components—delimiters(分隔符), identifiers(标识符), literals, and comments(注释).

Topics

■ Delimiters

■ Identifiers

■ Literals(字面量)

■ Comments

■ Whitespace Characters Between Lexical Units

Delimiters

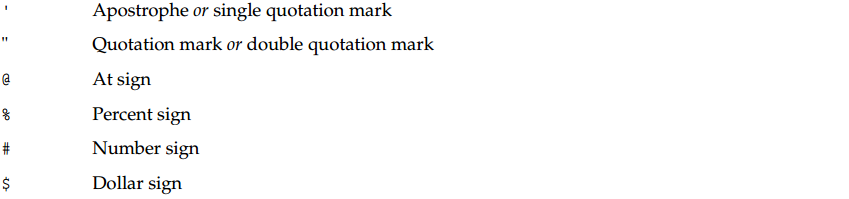

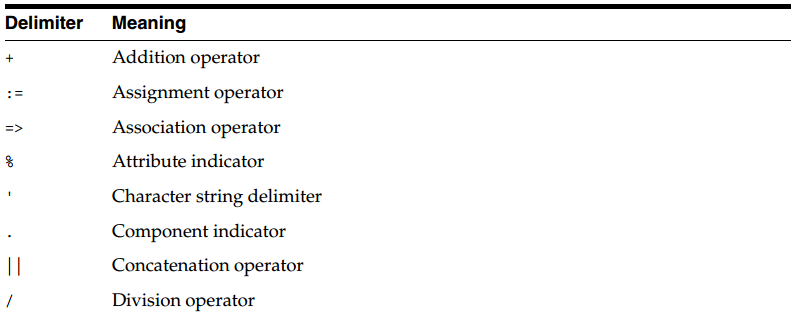

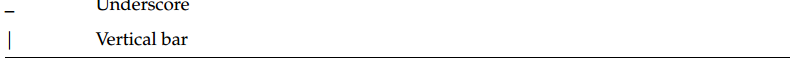

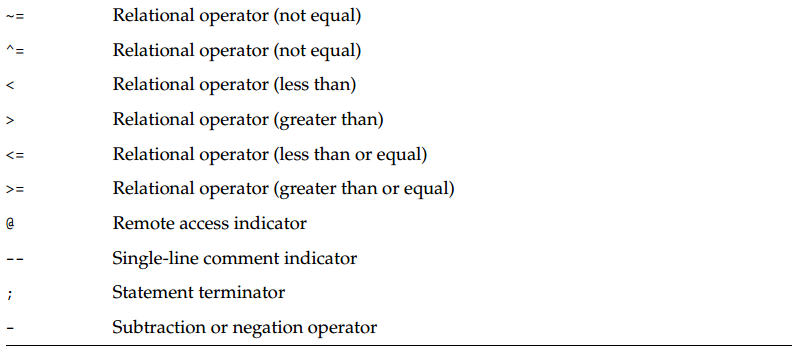

A delimiter is a character, or character combination(字符组合), that has a special meaning in PL/SQL.

Do not embed any others characters (including whitespace characters) inside a delimiter.

Table 2–2 summarizes the PL/SQL delimiters.

Table 2–2 PL/SQL Delimiters

Identifiers

Identifiers name PL/SQL elements, which include:

■ Constants

■ Cursors

■ Exceptions

■ Keywords

■ Labels

■ Packages

■ Reserved words(保留字)

■ Subprograms

■ Types

■ Variables

Every character in an identifier, alphabetic(字母) or not, is significant(有意义的).

For example, the identifiers lastname and last_name are different.

You must separate adjacent identifiers(分离相邻的标识符) by one or more whitespace characters or a punctuation character(标点字符).

Except as explained in “Quoted(引用) User-Defined Identifiers” on page 2-6, PL/SQL is case-insensitive(不分大小写) for identifiers.

For example, the identifiers lastname, LastName, and

LASTNAME are the same.

Topics

■ Reserved Words and Keywords

■ Predefined Identifiers

■ User-Defined Identifiers

Reserved Words and Keywords

Reserved words and keywords are identifiers that have special meaning in PL/SQL.

You cannot use reserved words as ordinary(一般的) user-defined identifiers.

You can use them as quoted user-defined identifiers, but it is not recommended(不推荐).

For more information, see “Quoted User-Defined Identifiers” on page 2-6.

You can use keywords as ordinary user-defined identifiers, but it is not recommended.

For lists of PL/SQL reserved words and keywords, see Table D–1 and Table D–2, respectively(分别地).

Predefined Identifiers

Predefined identifiers are declared in the predefined package STANDARD.

An example of a predefined identifier is the exception INVALID_NUMBER.

For a list of predefined identifiers, connect to Oracle Database as a user who has the DBA role and use this query:

SELECT TYPE_NAME FROM ALL_TYPES WHERE PREDEFINED=’YES’;

You can use predefined identifiers as user-defined identifiers, but it is not recommended.

Your local declaration overrides the global declaration (see “Scope and Visibility of Identifiers” on page 2-17).

User-Defined Identifiers

A user-defined identifier is:

■ Composed of(由 … 组成) characters from the database character set

■ Either ordinary or quoted

Tip: Make user-defined identifiers meaningful.

For example, the meaning of cost_per_thousand is obvious, but the meaning of cpt is not.

Ordinary User-Defined Identifiers An ordinary user-defined identifier:

■ Begins with a letter(字母)

■ Can include letters, digits, and these symbols(符号):

– Dollar sign ($)

– Number sign (#)

– Underscore(下划线) (_)

■ Is not a reserved word (listed in Table D–1).

The database character set defines which characters are classified(分类) as letters and digits.

The representation(表现) of the identifier in the database character set cannot exceed 30 bytes(超过30字节).

Examples of acceptable ordinary user-defined identifiers:

X

t2

phone#

credit_limit

LastName

oracle

numbermoney

$$tree

SN##

try_again_

Examples of unacceptable ordinary user-defined identifiers:

mine&yours

debit-amount

on/off

user id

Quoted User-Defined Identifiers A quoted user-defined identifier is enclosed in double quotation marks(双引号).

Between the double quotation marks, any characters from the

database character set are allowed except double quotation marks, new line characters,

and null characters.

For example, these identifiers are acceptable:

“X+Y”

“last name”

“on/off switch”

“employee(s)”

“* header info *”

The representation of the quoted identifier in the database character set cannot exceed 30 bytes (excluding the double quotation marks).

A quoted user-defined identifier is case-sensitive(有大小写之分的), with one exception: If a quoted(带引号的) user-defined identifier, without its enclosing double quotation marks, is a valid ordinary user-defined identifier, then the double quotation marks are optional in references to the identifier, and if you omit(省略) them, then the identifier is case-insensitive.

In Example 2–1, the quoted user-defined identifier “HELLO”, without its enclosing double quotation marks, is a valid ordinary user-defined identifier.

Therefore, the reference Hello is valid.

Example 2–1 Valid Case-Insensitive Reference to Quoted User-Defined Identifier

DECLARE

"HELLO" varchar2(10) := 'hello';

BEGIN

DBMS_Output.Put_Line(Hello);

END;

/Result:

hello

In Example 2–2, the reference “Hello” is invalid, because the double quotation marks make the identifier case-sensitive.

Example 2–2 Invalid Case-Insensitive Reference to Quoted User-Defined Identifier

DECLARE

"HELLO" varchar2(10) := 'hello';

BEGIN

DBMS_Output.Put_Line("Hello");

END;

/Result:

DBMS_Output.Put_Line(“Hello”);

*

ERROR at line 4:

ORA-06550: line 4, column 25:

PLS-00201: identifier ‘Hello’ must be declared

ORA-06550: line 4, column 3:

PL/SQL: Statement ignored

It is not recommended(推荐的), but you can use a reserved word as a quoted user-defined identifier.

Because a reserved word is not a valid ordinary user-defined identifier, you must always enclose the identifier in double quotation marks, and it is always case-sensitive.

Example 2–3 declares quoted user-defined identifiers “BEGIN”, “Begin”, and “begin”.

Although BEGIN, Begin, and begin represent the same reserved word, “BEGIN”,

“Begin”, and “begin” represent different identifiers.

Example 2–3 Reserved Word as Quoted User-Defined Identifier

DECLARE

"BEGIN" varchar2(15) := 'UPPERCASE';

"Begin" varchar2(15) := 'Initial Capital';

"begin" varchar2(15) := 'lowercase';

BEGIN

DBMS_Output.Put_Line("BEGIN");

DBMS_Output.Put_Line("Begin");

DBMS_Output.Put_Line("begin");

END;

/Result:

UPPERCASE

Initial Capital

lowercase

PL/SQL procedure successfully completed.

Example 2–4 references a quoted user-defined identifier that is a reserved word, neglecting(忽视) to enclose it in double quotation marks.

Example 2–4 Neglecting Double Quotation Marks

DECLARE

"HELLO" varchar2(10) := 'hello'; -- HELLO is not a reserved word

"BEGIN" varchar2(10) := 'begin'; -- BEGIN is a reserved word

BEGIN

DBMS_Output.Put_Line(Hello); -- Double quotation marks are optional

DBMS_Output.Put_Line(BEGIN); -- Double quotation marks are required

end;

/Result:

DBMS_Output.Put_Line(BEGIN); – Double quotation marks are required

*

ERROR at line 6:

ORA-06550: line 6, column 24:

PLS-00103: Encountered the symbol “BEGIN” when expecting one of the following:

( ) - + case mod new not null

table continue avg count current exists max min prior sql

stddev sum variance execute multiset the both leading

trailing forall merge year month day hour minute second

timezone_hour timezone_minute timezone_region timezone_abbr

time timestamp interval date

DECLARE

"HELLO" varchar2(10) := 'hello'; -- HELLO is not a reserved word

"BEGIN" varchar2(10) := 'begin'; -- BEGIN is a reserved word

BEGIN

DBMS_Output.Put_Line(Hello); -- Identifier is case-insensitive

DBMS_Output.Put_Line("Begin"); -- Identifier is case-sensitive

END;

/Result:

DBMS_Output.Put_Line(“Begin”); – Identifier is case-sensitive

*

ERROR at line 6:

ORA-06550: line 6, column 25:

PLS-00201: identifier ‘Begin’ must be declared

ORA-06550: line 6, column 3:

PL/SQL: Statement ignored

Literals(字面量)

A literal is a value that is neither represented by an identifier nor calculated(计算) from other values.

For example, 123 is an integer literal and ‘abc’ is a character literal, but 1+2 is not a literal.

PL/SQL literals include all SQL literals (described in Oracle Database SQL Language Reference) and BOOLEAN literals (which SQL does not have).

A BOOLEAN literal is the predefined logical value TRUE, FALSE, or NULL.

NULL represents an unknown value.

Note: Like Oracle Database SQL Language Reference, this document uses the terms character literal(字符文字条款) and string interchangeably(字符串可以互换)

When using character literals in PL/SQL, remember:

■ Character literals are case-sensitive.

For example, ‘Z’ and ‘z’ are different.

■ Whitespace characters are significant(有效的).

For example, these literals are different:

‘abc’

’ abc’

‘abc ’

’ abc ’

‘a b c’

■ PL/SQL has no line-continuation character that means “this string continues on the next source line.”

If you continue a string on the next source line, then the

string includes a line-break character.

For example, this PL/SQL code:

BEGIN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('This string breaks

here.');

END;

/Prints this:

This string breaks

here.

If your string does not fit(装上) on a source line and you do not want it to include a line-break character, then construct the string with the concatenation operator(连接字符) (||).

For example, this PL/SQL code:

BEGIN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('This string ' ||

'contains no line-break character.');

END;

/Prints this:

This string contains no line-break character.

For more information about the concatenation operator, see “Concatenation Operator” on page 2-24.

■ ‘0’ through ‘9’ are not equivalent(等价的) to the integer literals 0 through 9.

However, because PL/SQL converts them to integers, you can use them in arithmetic expressions(算术表达式).

■ A character literal with zero characters has the value NULL and is called a null string.

However, this NULL value is not the BOOLEAN value NULL.

■ An ordinary character literal(普通字符字面量) is composed of characters in the database character set.

For information about the database character set, see Oracle Database Globalization Support Guide.

■ A national character literal is composed of characters in the national character set.

For information about the national character set, see Oracle Database Globalization Support Guide.

Comments

The PL/SQL compiler ignores comments.

Their purpose is to help other application developers understand your source text(源程序正文).

Typically, you use comments to describe the purpose and use of each code segment.

You can also disable obsolete or unfinished pieces of code(废弃的或者未完成的代码片段) by turning them into comments.

Topics

■ Single-Line Comments

■ Multiline Comments

See Also: “Comment” on page 13-34

Single-Line Comments

A single-line comment begins with – and extends to the end of the line.

Caution(警告): Do not put a single-line comment in a PL/SQL block to be processed dynamically by an Oracle Precompiler program(Oracle 预编译程序).

The Oracle Precompiler program ignores end-of-line characters, which means that a single-line comment ends when the block ends.

Example 2–6 has three single-line comments.

Example 2–6 Single-Line Comments

DECLARE

howmany NUMBER;

num_tables NUMBER;

BEGIN

-- Begin processing

SELECT COUNT(*) INTO howmany

FROM USER_OBJECTS

WHERE OBJECT_TYPE = 'TABLE'; -- Check number of tables

num_tables := howmany; -- Compute another value

END;

/While testing or debugging a program, you can disable a line of code by making it a comment.

For example:

– DELETE FROM employees WHERE comm_pct IS NULL

Multiline Comments

A multiline comment begins with /, ends with /, and can span(跨越) multiple lines.

Example 2–7 has two multiline comments. (The SQL function TO_CHAR returns the character equivalent of its argument. For more information about TO_CHAR, see Oracle

Database SQL Language Reference.)

Example 2–7 Multiline Comments

DECLARE

some_condition BOOLEAN;

pi NUMBER := 3.1415926;

radius NUMBER := 15;

area NUMBER;

BEGIN

/* Perform some simple tests and assignments */

IF 2 + 2 = 4 THEN

some_condition := TRUE;

/* We expect this THEN to always be performed */

END IF;

/* This line computes the area of a circle using pi,

which is the ratio between the circumference and diameter.

After the area is computed, the result is displayed. */

area := pi * radius**2;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('The area is: ' || TO_CHAR(area));

END;

/Result:

The area is: 706.858335

You can use multiline comment delimiters to “comment out” sections of code.

When doing so, be careful not to cause nested(嵌套的) multiline comments.

One multiline comment cannot contain another multiline comment.

However, a multiline comment can contain a single-line comment.

For example, this causes a syntax error:

/*

IF 2 + 2 = 4 THEN

some_condition := TRUE;

/* We expect this THEN to always be performed */

END IF;

*/This does not cause a syntax error:

/*

IF 2 + 2 = 4 THEN

some_condition := TRUE;

-- We expect this THEN to always be performed

END IF;

*/Whitespace Characters Between Lexical Units

You can put whitespace characters between lexical units, which often makes your source text easier to read, as Example 2–8 shows.

Example 2–8 Whitespace Characters Improving Source Text Readability

DECLARE

x NUMBER := 10;

y NUMBER := 5;

max NUMBER;

BEGIN

IF x>y THEN max:=x;ELSE max:=y;END IF; -- correct but hard to read

-- Easier to read:

IF x > y THEN

max:=x;

ELSE

max:=y;

END IF;

END;

/Declarations

A declaration allocates storage space for a value of a specified data type, and names the storage location so that you can reference it.

You must declare objects before you can reference them. Declarations can appear in the declarative part of any block, subprogram, or package.

Topics

■ Variable Declarations

■ Constant Declarations

■ Initial Values of Variables and Constants

■ NOT NULL Constraint

■ %TYPE Attribute

For information about declaring objects other than variables and constants, see the syntax of declare_section in “Block” on page 13-9.

NOT NULL Constraint

You can impose(强加) the NOT NULL constraint on a scalar variable(标量变量) or constant (or scalar component of a composite variable(复合变量) or constant).

The NOT NULL constraint prevents assigning a null value to the item.

The item can acquire this constraint either implicitly(隐式地)

(from its data type) or explicitly(显式地).

A scalar variable declaration that specifies NOT NULL, either implicitly or explicitly, must assign an initial value to the variable (because the default initial value for a scalar variable is NULL).

In Example 2–9, the variable acct_id acquires the NOT NULL constraint explicitly, and the variables a, b, and c acquire it from their data types.

Example 2–9 Variable Declaration with NOT NULL Constraint

DECLARE

acct_id INTEGER(4) NOT NULL := 9999;

a NATURALN := 9999;

b POSITIVEN := 9999;

c SIMPLE_INTEGER := 9999;

BEGIN

NULL;

END;

/ PL/SQL treats(对待) any zero-length string as a NULL value.

This includes values returned by character functions and BOOLEAN expressions.

In Example 2–10, all variables are initialized to NULL.

DECLARE

null_string VARCHAR2(80) := TO_CHAR('');

address VARCHAR2(80);

zip_code VARCHAR2(80) := SUBSTR(address, 25, 0);

name VARCHAR2(80);

valid BOOLEAN := (name != '');

BEGIN

NULL;

END;

/To test for a NULL value, use the “IS [NOT] NULL Operator” on page 2-33.

Variable Declarations

A variable declaration always specifies the name and data type of the variable.

For most data types, a variable declaration can also specify an initial value.

The variable name must be a valid user-defined identifier (see “User-Defined Identifiers” on page 2-5).

The data type can be any PL/SQL data type.

The PL/SQL data types include the SQL data types.

A data type is either scalar (without internal components(内部组件)) or composite(复合的) (with internal components).

Example 2–11 declares several variables with scalar data types.

Example 2–11 Scalar Variable Declarations

DECLARE

part_number NUMBER(6); -- SQL data type

part_name VARCHAR2(20); -- SQL data type

in_stock BOOLEAN; -- PL/SQL-only data type

part_price NUMBER(6,2); -- SQL data type

part_description VARCHAR2(50); -- SQL data type

BEGIN

NULL;

END;

/See Also:

■ “Scalar Variable Declaration” on page 13-124 for scalar variable declaration syntax

■ Chapter 3, “PL/SQL Data Types” for information about scalar data types

■ Chapter 5, “PL/SQL Collections and Records,” for information about composite data types and variables

Constant Declarations

The information in “Variable Declarations” on page 2-13 also applies to constant declarations, but a constant declaration has two more requirements: the keyword CONSTANT and the initial value of the constant. (The initial value of a constant is its permanent value(永久值).)

Example 2–12 declares three constants with scalar data types.

Example 2–12 Constant Declarations

DECLARE

credit_limit CONSTANT REAL := 5000.00; -- SQL data type

max_days_in_year CONSTANT INTEGER := 366; -- SQL data type

urban_legend CONSTANT BOOLEAN := FALSE; -- PL/SQL-only data type

BEGIN

NULL;

END;

/See Also: “Constant Declaration” on page 13-36 for constant declaration syntax

Initial Values of Variables and Constants

In a variable declaration, the initial value is optional unless you specify the NOT NULL constraint (for details, see “NOT NULL Constraint” on page 2-12).

In a constant declaration, the initial value is required.

If the declaration is in a block or subprogram, the initial value is assigned to the variable or constant every time control passes to the block or subprogram.

If the declaration is in a package specification, the initial value is assigned to the variable or constant for each session (whether the variable or constant is public or private).

To specify the initial value, use either the assignment operator(赋值运算符) (:=) or the keyword DEFAULT, followed by an expression.

The expression can include previously(以前的) declared constants and previously initialized variables.

Example 2–13 assigns initial values to the constant and variables that it declares.

The initial value of area depends on the previously declared constant pi and the previously initialized variable radius.

Example 2–13 Variable and Constant Declarations with Initial Values

DECLARE

hours_worked INTEGER := 40;

employee_count INTEGER := 0;

pi CONSTANT REAL := 3.14159;

radius REAL := 1;

area REAL := (pi * radius**2);

BEGIN

NULL;

END;

/If you do not specify an initial value for a variable, assign a value to it before using it in any other context.

In Example 2–14, the variable counter has the initial value NULL, by default.

As the example shows (using the “IS [NOT] NULL Operator” on page 2-33) NULL is different from zero.

Example 2–14 Variable Initialized to NULL by Default

DECLARE

counter INTEGER; -- initial value is NULL by default

BEGIN

counter := counter + 1; -- NULL + 1 is still NULL

IF counter IS NULL THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('counter is NULL.');

END IF;

END;

/Result:

counter is NULL.

See Also:

■ “Declaring Associative Array Constants” on page 5-6 for

information about declaring constant associative arrays(常数关联数组)

■ “Declaring Record Constants” on page 5-40 for information about declaring constant records

%TYPE Attribute

The %TYPE attribute lets you declare a data item of the same data type as a previously declared variable or column (without knowing what that type is).

If the declaration of the referenced item changes, then the declaration of the referencing item changes accordingly.

The syntax of the declaration is:

referencing_item referenced_item%TYPE;

For the kinds of items that can be referencing and referenced items, see “%TYPE Attribute” on page 13-134.

The referencing item inherits(继承) the following from the referenced item:

■ Data type and size

■ Constraints (unless the referenced item is a column)

The referencing item does not inherit(继承) the initial value of the referenced item.

Therefore, if the referencing item specifies or inherits the NOT NULL constraint, you must specify an initial value for it.

The %TYPE attribute is particularly(特别地) useful when declaring variables to hold database values.

The syntax for declaring a variable of the same type as a column is:

variable_name table_name.column_name%TYPE;

In Example 2–15, the variable surname inherits the data type and size of the column employees.last_name, which has a NOT NULL constraint.

Because surname does not inherit the NOT NULL constraint, its declaration does not need an initial value.

Example 2–15 Declaring Variable of Same Type as Column

DECLARE

surname employees.last_name%TYPE;

BEGIN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('surname=' || surname);

END;

/Result:

surname=

In Example 2–16, the variable surname inherits the data type, size, and NOT NULL constraint of the variable name.

Because surname does not inherit the initial value of name, its declaration needs an initial value (which cannot exceed 25 characters).

Example 2–16 Declaring Variable of Same Type as Another Variable

DECLARE

name VARCHAR(25) NOT NULL := 'Smith';

surname name%TYPE := 'Jones';

BEGIN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('name=' || name);

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('surname=' || surname);

END;

/Result:

name=Smith

surname=Jones

See Also: “%ROWTYPE Attribute” on page 5-44, which lets you declare a record variable that represents either a full or partial row of a database table or view.

References to Identifiers

When referencing an identifier, you use a name that is either simple, qualified, remote, or both qualified and remote.

The simple name of an identifier is the name in its declaration. For example:

DECLARE

a INTEGER; -- Declaration

BEGIN

a := 1; -- Reference with simple name

END;

/If an identifier is declared in a named PL/SQL unit, you can (and sometimes must) reference it with its qualified name. The syntax (called dot notation(点表示法)) is:

unit_name.simple_identifier_nameFor example, if package p declares identifier a, you can reference the identifier with the qualified name p.a.

The unit name also can (and sometimes must) be qualified. You must qualify an identifier when it is not visible(不可见) (see “Scope and Visibility of Identifiers” on page 2-17).

If the identifier names an object on a remote database, you must reference it with its remote name.

The syntax is:

simple_identifier_name@link_to_remote_databaseIf the identifier is declared in a PL/SQL unit on a remote database, you must reference it with its qualified remote name.

The syntax is:

unit_name.simple_identifier_name@link_to_remote_databaseYou can create synonyms for remote schema objects, but you cannot create synonyms for objects declared in PL/SQL subprograms or packages.

To create a synonym, use the SQL statement CREATE SYNONYM, explained in Oracle Database SQL Language

Reference.

For information about how PL/SQL resolves ambiguous(两意) names, see Appendix B, “PL/SQL Name Resolution”.

Note: You can reference identifiers declared in the packages STANDARD and DBMS_STANDARD without qualifying them with the package names, unless you have declared a local identifier with the same name (see “Scope and Visibility of Identifiers” on page 2-17).

Scope and Visibility of Identifiers

The scope of an identifier is the region(区域) of a PL/SQL unit from which you can reference the identifier.

The visibility of an identifier is the region of a PL/SQL unit from which you can reference the identifier without qualifying(取得资格) it.

An identifier is local to the PL/SQL unit that declares it.

If that unit has subunits(子单元), the identifier is global to them.

If a subunit redeclares a global identifier, then inside the subunit, both identifiers are in scope, but only the local identifier is visible.

To reference the global identifier, the subunit must qualify it with the name of the unit that declared it.

If that unit has no name, then the subunit cannot reference the global identifier.

A PL/SQL unit cannot reference identifiers declared in other units at the same level, because those identifiers are neither local nor global to the block.

Example 2–17 shows the scope and visibility of several identifiers.

The first sub-block redeclares the global identifier a.

To reference the global variable a, the first sub-block

would have to qualify it with the name of the outer block—but the outer block has no name.

Therefore, the first sub-block cannot reference the global variable a; it can reference only its local variable a.

Because the sub-blocks are at the same level, the first

sub-block cannot reference d, and the second sub-block cannot reference c.

Example 2–17 Scope and Visibility of Identifiers

-- Outer block:

DECLARE

a CHAR; -- Scope of a (CHAR) begins

b REAL; -- Scope of b begins

BEGIN

-- Visible: a (CHAR), b

-- First sub-block:

DECLARE

a INTEGER; -- Scope of a (INTEGER) begins

c REAL; -- Scope of c begins

BEGIN

-- Visible: a (INTEGER), b, c

NULL;

END; -- Scopes of a (INTEGER) and c end

-- Second sub-block:

DECLARE

d REAL; -- Scope of d begins

BEGIN

-- Visible: a (CHAR), b, d

NULL;

END; -- Scope of d ends

-- Visible: a (CHAR), b

END; -- Scopes of a (CHAR) and b end

/Example 2–18 labels the outer block with the name outer. Therefore, after the sub-block redeclares the global variable birthdate, it can reference that global variable by qualifying its name with the block label.

The sub-block can also reference its local variable birthdate, by its simple name.

Example 2–18 Qualifying Redeclared Global Identifier with Block Label

<<outer>> -- label

DECLARE

birthdate DATE := TO_DATE('09-AUG-70', 'DD-MON-YY');

BEGIN

DECLARE

birthdate DATE := TO_DATE('29-SEP-70', 'DD-MON-YY');

BEGIN

IF birthdate = outer.birthdate THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE ('Same Birthday');

ELSE

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE ('Different Birthday');

END IF;

END;

END;

/Result:

Different BirthdayIn Example 2–19, the procedure check_credit declares a variable, rating, and a function, check_rating. The function redeclares the variable.

Then the function references the global variable by qualifying it with the procedure name.

Example 2–19 Qualifying Identifier with Subprogram Name

CREATE OR REPLACE PROCEDURE check_credit(credit_limit NUMBER) AS

rating NUMBER := 3;

FUNCTION check_rating RETURN BOOLEAN IS

rating NUMBER := 1;

over_limit BOOLEAN;

BEGIN

IF check_credit.rating <= credit_limit THEN

-- reference global variable

over_limit := FALSE;

ELSE

over_limit := TRUE;

rating := credit_limit; -- reference local variable

END IF;

RETURN over_limit;

END check_rating;

BEGIN

IF check_rating THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('Credit rating over limit (' ||

TO_CHAR(credit_limit) || '). ' || 'Rating: ' ||

TO_CHAR(rating));

ELSE

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('Credit rating OK. ' || 'Rating: ' ||

TO_CHAR(rating));

END IF;

END;

/Result:

Credit rating over limit (1). Rating: 3You cannot declare the same identifier twice in the same PL/SQL unit.

If you do, an error occurs when you reference the duplicate(副本) identifier, as Example 2–20 shows.

Example 2–20 Duplicate Identifiers in Same Scope

DECLARE

id BOOLEAN;

id VARCHAR2(5); -- duplicate identifier

BEGIN

id := FALSE;

END;

/Result:

id := FALSE;

*

ERROR at line 5:

ORA-06550: line 5, column 3:

PLS-00371: at most one declaration for 'ID' is permitted

ORA-06550: line 5, column 3:

PL/SQL: Statement ignoredYou can declare the same identifier in two different units.

The two objects represented by the identifier are distinct. Changing one does not affect the other, as Example 2–21

shows.

Example 2–21 Declaring Same Identifier in Different Units

DECLARE

PROCEDURE p IS

x VARCHAR2(1);

BEGIN

x := 'a'; -- Assign the value 'a' to x

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('In procedure p, x = ' || x);

END;

PROCEDURE q IS

x VARCHAR2(1);

BEGIN

x := 'b'; -- Assign the value 'b' to x

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('In procedure q, x = ' || x);

END;

BEGIN

p;

q;

END;

/

Result:

In procedure p, x = a

In procedure q, x = bIn the same scope, give labels and subprograms unique names to avoid confusion(避免混淆) and unexpected results.

In Example 2–22, echo is the name of both a block and a subprogram.

Both the block and the subprogram declare a variable named x.

In the subprogram, echo.x refers to the local variable x, not to the global variable x.

Example 2–22 Label and Subprogram with Same Name in Same Scope

<<echo>>

DECLARE

x NUMBER := 5;

PROCEDURE echo AS

x NUMBER := 0;

BEGIN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('x = ' || x);

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('echo.x = ' || echo.x);

END;

BEGIN

echo;

END;

/Result:

x = 0

echo.x = 0Example 2–23 has two labels for the outer block, compute_ratio and another_label.

The second label appears again in the inner block. In the inner block, another_

label.denominator refers to the local variable denominator, not to the global variable

denominator, which results in the error ZERO_DIVIDE.

Example 2–23 Block with Multiple and Duplicate Labels

<<compute_ratio>>

<<another_label>>

DECLARE

numerator NUMBER := 22;

denominator NUMBER := 7;

BEGIN

<<another_label>>

DECLARE

denominator NUMBER := 0;

BEGIN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('Ratio with compute_ratio.denominator = ');

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(numerator/compute_ratio.denominator);

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('Ratio with another_label.denominator = ');

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE(numerator/another_label.denominator);

EXCEPTION

WHEN ZERO_DIVIDE THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('Divide-by-zero error: can''t divide '

|| numerator || ' by ' || denominator);

WHEN OTHERS THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('Unexpected error.');

END another_label;

END compute_ratio;

/Result:

Ratio with compute_ratio.denominator =

3.14285714285714285714285714285714285714

Ratio with another_label.denominator =

Divide-by-zero error: cannot divide 22 by 0Assigning Values to Variables

After declaring a variable, you can assign a value to it in these ways:

■ Use the assignment statement to assign it the value of an expression.

■ Use the SELECT INTO or FETCH statement to assign it a value from a table.

■ Pass it to a subprogram as an OUT or IN OUT parameter, and then assign the value inside the subprogram.

The variable and the value must have compatible(兼容) data types.

One data type is compatible with another data type if it can be implicitly(隐式地) converted to that type.

For information about implicit data conversion, see Oracle Database SQL Language Reference.

Topics

■ Assigning Values to Variables with the Assignment Statement

■ Assigning Values to Variables with the SELECT INTO Statement

■ Assigning Values to Variables as Parameters of a Subprogram

■ Assigning Values to BOOLEAN Variables

See Also:

■ “Assigning Values to Collection Variables” on page 5-15

■ “Assigning Values to Record Variables” on page 5-49

■ “FETCH Statement” on page 13-71

Assigning Values to Variables with the Assignment Statement

To assign the value of an expression to a variable, use this form of the assignment statement:

variable_name := expression;For the complete syntax of the assignment statement, see “Assignment Statement” on page 13-3.

For the syntax of an expression, see “Expression” on page 13-61.

Example 2–24 declares several variables (specifying initial values for some) and then uses assignment statements to assign the values of expressions to them.

Example 2–24 Assigning Values to Variables with Assignment Statement

DECLARE -- You can assign initial values here

wages NUMBER;

hours_worked NUMBER := 40;

hourly_salary NUMBER := 22.50;

bonus NUMBER := 150;

country VARCHAR2(128);

counter NUMBER := 0;

done BOOLEAN;

valid_id BOOLEAN;

emp_rec1 employees%ROWTYPE;

emp_rec2 employees%ROWTYPE;

TYPE commissions IS TABLE OF NUMBER INDEX BY PLS_INTEGER;

comm_tab commissions;

BEGIN -- You can assign values here too

wages := (hours_worked * hourly_salary) + bonus;

country := 'France';

country := UPPER('Canada');

done := (counter > 100);

valid_id := TRUE;

emp_rec1.first_name := 'Antonio';

emp_rec1.last_name := 'Ortiz';

emp_rec1 := emp_rec2;

comm_tab(5) := 20000 * 0.15;

END;

/Assigning Values to Variables with the SELECT INTO Statement

A simple form of the SELECT INTO statement is:

SELECT select_item [, select_item ]...

INTO variable_name [, variable_name ]...

FROM table_name;For each select_item, there must be a corresponding(相应的), type-compatible(类型兼容的) variable_name.

Because SQL does not have a BOOLEAN type, variable_name cannot be a BOOLEAN variable.

For the complete syntax of the SELECT INTO statement, see “SELECT INTO Statement” on page 13-126.

Example 2–25 uses a SELECT INTO statement to assign to the variable bonus the value that is 10% of the salary of the employee whose employee_id is 100.

Example 2–25 Assigning Value to Variable with SELECT INTO Statement

DECLARE

bonus NUMBER(8,2);

BEGIN

SELECT salary * 0.10 INTO bonus

FROM employees

WHERE employee_id = 100;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('bonus = ' || TO_CHAR(bonus));

END;

/Result:

bonus = 2400Assigning Values to Variables as Parameters of a Subprogram

If you pass a variable to a subprogram as an OUT or IN OUT parameter, and the subprogram assigns a value to the parameter, the variable retains that value after the

subprogram finishes running.

For more information, see “Subprogram Parameters” on

page 8-9.

Example 2–26 passes the variable new_sal to the procedure adjust_salary.

The procedure assigns a value to the corresponding formal parameter(相应形式的参数), sal.

Because sal is an IN OUT parameter, the variable new_sal retains the assigned value after the procedure finishes running.

Example 2–26 Assigning Value to Variable as IN OUT Subprogram Parameter

DECLARE

emp_salary NUMBER(8,2);

PROCEDURE adjust_salary (

emp NUMBER,

sal IN OUT NUMBER,

adjustment NUMBER

) IS

BEGIN

sal := sal + adjustment;

END;

BEGIN

SELECT salary INTO emp_salary

FROM employees

WHERE employee_id = 100;

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE

('Before invoking procedure, emp_salary: ' || emp_salary);

adjust_salary (100, emp_salary, 1000);

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE

('After invoking procedure, emp_salary: ' || emp_salary);

END;

/Result:

Before invoking procedure, emp_salary: 24000

After invoking procedure, emp_salary: 25000Assigning Values to BOOLEAN Variables

The only values that you can assign to a BOOLEAN variable are TRUE, FALSE, and NULL.

Example 2–27 initializes the BOOLEAN variable done to NULL by default, assigns it the literal value FALSE, compares it to the literal value TRUE, and assigns it the value of a BOOLEAN expression.

Example 2–27 Assigning Value to BOOLEAN Variable

DECLARE

done BOOLEAN; -- Initial value is NULL by default

counter NUMBER := 0;

BEGIN

done := FALSE; -- Assign literal value

WHILE done != TRUE -- Compare to literal value

LOOP

counter := counter + 1;

done := (counter > 500); -- Assign value of BOOLEAN expression

END LOOP;

END;

/For more information about the BOOLEAN data type, see “BOOLEAN Data Type” on page 3-7.

Expressions

An expression always returns a single value.

The simplest expressions, in order of increasing complexity(复杂性), are:

1. A single constant or variable (for example, a)

2. A unary operator(一元操作符) and its single operand(运算对象) (for example, -a)

3. A binary operator(二元运算符) and its two operands (for example, a+b)

An operand can be a variable, constant, literal, operator, function invocation(函数调用), or placeholde(占位符)—or another expression.

Therefore, expressions can be arbitrarily complex(任意复杂的).

For expression syntax, see “Expression” on page 13-61.

The data types of the operands determine the data type of the expression.

Every time the expression is evaluated(评估的), a single value of that data type results.

The data type of that result is the data type of the expression.

Topics

■ Concatenation Operator(连接运算)

■ Operator Precedence(运算优先级)

■ Logical Operators

■ Short-Circuit Evaluation(短路评估)

■ Comparison Operators

■ BOOLEAN Expressions

■ CASE Expressions

■ SQL Functions in PL/SQL Expressions

Concatenation Operator

The concatenation operator (||) appends one string operand to another, as Example 2–28 shows.

Example 2–28 Concatenation Operator

DECLARE

x VARCHAR2(4) := 'suit';

y VARCHAR2(4) := 'case';

BEGIN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE (x || y);

END;

/Result:

suitcaseThe concatenation operator ignores null operands, as Example 2–29 shows.

Example 2–29 Concatenation Operator with NULL Operands

BEGIN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE ('apple' || NULL || NULL || 'sauce');

END;

/Result:

applesauceFor more information about the syntax of the concatenation operator, see “character_expression ::=” on page 13-63.

Operator Precedence

An operation is either a unary operator and its single operand or a binary operator and its two operands.

The operations in an expression are evaluated in order of

operator precedence.

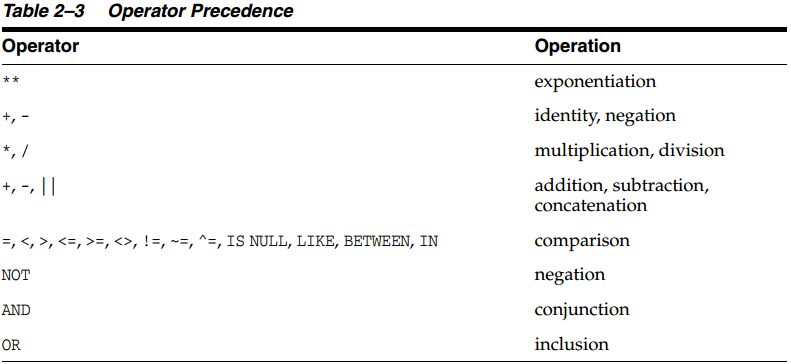

Table 2–3 shows operator precedence from highest to lowest. Operators with equal precedence are evaluated in no particular order.

To control the order of evaluation, enclose operations in parentheses(将操作置于括号中), as in Example 2–30.

Example 2–30 Controlling Evaluation Order with Parentheses

DECLARE

a INTEGER := 1+2**2;

b INTEGER := (1+2)**2;

BEGIN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('a = ' || TO_CHAR(a));

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('b = ' || TO_CHAR(b));

END;

/Result:

a = 5

b = 9When parentheses are nested, the most deeply nested operations are evaluated first.

In Example 2–31, the operations (1+2) and (3+4) are evaluated first, producing the values 3 and 7, respectively(分别的).

Next, the operation 3*7 is evaluated(求值), producing the result 21.

Finally, the operation 21/7 is evaluated, producing the final value 3.

Example 2–31 Expression with Nested Parentheses

DECLARE

a INTEGER := ((1+2)*(3+4))/7;

BEGIN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('a = ' || TO_CHAR(a));

END;

/Result:

a = 3You can also use parentheses to improve readability, as in Example 2–32, where the parentheses do not affect evaluation order.

Example 2–32 Improving Readability with Parentheses

DECLARE

a INTEGER := 2**2*3**2;

b INTEGER := (2**2)*(3**2);

BEGIN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('a = ' || TO_CHAR(a));

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('b = ' || TO_CHAR(b));

END;

/Result:

a = 36

b = 36Example 2–33 shows the effect of operator precedence and parentheses in several more complex expressions.

Example 2–33 Operator Precedence

DECLARE

salary NUMBER := 60000;

commission NUMBER := 0.10;

BEGIN

-- Division has higher precedence than addition:

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('5 + 12 / 4 = ' || TO_CHAR(5 + 12 / 4));

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('12 / 4 + 5 = ' || TO_CHAR(12 / 4 + 5));

-- Parentheses override default operator precedence:

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('8 + 6 / 2 = ' || TO_CHAR(8 + 6 / 2));

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('(8 + 6) / 2 = ' || TO_CHAR((8 + 6) / 2));

-- Most deeply nested operation is evaluated first:

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('100 + (20 / 5 + (7 - 3)) = ' ||

TO_CHAR(100 + (20 / 5 + (7 - 3))));

-- Parentheses, even when unnecessary, improve readability:

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('(salary * 0.05) + (commission * 0.25) = ' ||

TO_CHAR((salary * 0.05) + (commission * 0.25)));

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('salary * 0.05 + commission * 0.25 = ' ||

TO_CHAR(salary * 0.05 + commission * 0.25));

END;

/Result:

5 + 12 / 4 = 8

12 / 4 + 5 = 8

8 + 6 / 2 = 11

(8 + 6) / 2 = 7

100 + (20 / 5 + (7 - 3)) = 108

(salary * 0.05) + (commission * 0.25) = 3000.025

salary * 0.05 + commission * 0.25 = 3000.025Logical Operators

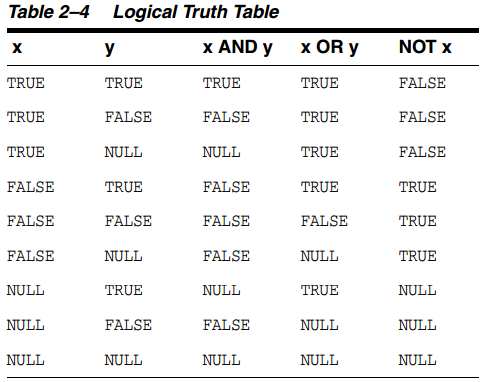

The logical operators AND, OR, and NOT follow the tri-state(三态) logic shown in Table 2–4.

AND and OR are binary operators; NOT is a unary operator.

Example 2–34 creates a procedure, print_boolean, that prints the value of a BOOLEAN variable.

The procedure uses the “IS [NOT] NULL Operator” on page 2-33. Several examples in this chapter invoke print_boolean.

Example 2–34 Procedure Prints BOOLEAN Variable

CREATE OR REPLACE PROCEDURE print_boolean (

b_name VARCHAR2,

b_value BOOLEAN

) AUTHID DEFINER IS

BEGIN

IF b_value IS NULL THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE (b_name || ' = NULL');

ELSIF b_value = TRUE THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE (b_name || ' = TRUE');

ELSE

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE (b_name || ' = FALSE');

END IF;

END;

/As Table 2–4 and Example 2–35 show, AND returns TRUE if and only if both operands are TRUE.

DECLARE

PROCEDURE print_x_and_y(x BOOLEAN, y BOOLEAN) IS

BEGIN

print_boolean('x', x);

print_boolean('y', y);

print_boolean('x AND y', x AND y);

END print_x_and_y;

BEGIN

print_x_and_y(FALSE, FALSE);

print_x_and_y(TRUE, FALSE);

print_x_and_y(FALSE, TRUE);

print_x_and_y(TRUE, TRUE);

print_x_and_y(TRUE, NULL);

print_x_and_y(FALSE, NULL);

print_x_and_y(NULL, TRUE);

print_x_and_y(NULL, FALSE);

END;

/Result:

x = FALSE

y = FALSE

x AND y = FALSE

x = TRUE

y = FALSE

x AND y = FALSE

x = FALSE

y = TRUE

x AND y = FALSE

x = TRUE

y = TRUE

x AND y = TRUE

x = TRUE

y = NULL

x AND y = NULL

x = FALSE

y = NULL

x AND y = FALSE

x = NULL

y = TRUE

x AND y = NULL

x = NULL

y = FALSE

x AND y = FALSE

As Table 2–4 and Example 2–36 show, OR returns TRUE if either operand is TRUE.

(Example 2–36 invokes the print_boolean procedure from Example 2–35.)

Example 2–36 OR Operator

DECLARE

PROCEDURE print_x_or_y (

x BOOLEAN,

y BOOLEAN

) IS

BEGIN

print_boolean ('x', x);

print_boolean ('y', y);

print_boolean ('x OR y', x OR y);

END print_x_or_y;

BEGIN

print_x_or_y (FALSE, FALSE);

print_x_or_y (TRUE, FALSE);

print_x_or_y (FALSE, TRUE);

print_x_or_y (TRUE, TRUE);

print_x_or_y (TRUE, NULL);

print_x_or_y (FALSE, NULL);

print_x_or_y (NULL, TRUE);

print_x_or_y (NULL, FALSE);

END;

/Result:

x = FALSE

y = FALSE

x OR y = FALSE

x = TRUE

y = FALSE

x OR y = TRUE

x = FALSE

y = TRUE

x OR y = TRUE

x = TRUE

y = TRUE

x OR y = TRUE

x = TRUE

y = NULL

x OR y = TRUE

x = FALSE

y = NULL

x OR y = NULL

x = NULL

y = TRUE

x OR y = TRUE

x = NULL

y = FALSE

x OR y = NULLAs Table 2–4 and Example 2–37 show, NOT returns the opposite of its operand, unless the operand is NULL.

NOT NULL returns NULL, because NULL is an indeterminate(不确定的) value.

(Example 2–37 invokes the print_boolean procedure from Example 2–35.)

Example 2–37 NOT Operator

DECLARE

PROCEDURE print_not_x (

x BOOLEAN

) IS

BEGIN

print_boolean ('x', x);

print_boolean ('NOT x', NOT x);

END print_not_x;

BEGIN

print_not_x (TRUE);

print_not_x (FALSE);

print_not_x (NULL);

END;

/Result:

x = TRUE

NOT x = FALSE

x = FALSE

NOT x = TRUE

x = NULL

NOT x = NULLIn Example 2–38, you might expect the sequence of statements to run because x and y seem unequal.

But, NULL values are indeterminate.

Whether x equals y is unknown.

Therefore, the IF condition yields(产生) NULL and the sequence of statements is bypassed(忽视).

Example 2–38 NULL Value in Unequal Comparison

DECLARE

x NUMBER := 5;

y NUMBER := null;

BEGIN

IF x != y THEN

-- yields NULL, not TRUE

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('x != y'); -- not run

ELSIF x = y THEN

-- also yields NULL

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('x = y');

ELSE

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('Can''t tell if x and y are equal or not.');

END IF;

END;

/Result:

Can't tell if x and y are equal or not.In Example 2–39, you might expect the sequence of statements to run because a and b seem equal.

But, again, that is unknown, so the IF condition yields NULL and the sequence of statements(语句序列) is bypassed.

Example 2–39 NULL Value in Equal Comparison

DECLARE

a NUMBER := NULL;

b NUMBER := NULL;

BEGIN

IF a = b THEN

-- yields NULL, not TRUE

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('a = b'); -- not run

ELSIF a != b THEN

-- yields NULL, not TRUE

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('a != b'); -- not run

ELSE

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('Can''t tell if two NULLs are equal');

END IF;

END;

/

Result:

Can't tell if two NULLs are equalIn Example 2–40, the two IF statements appear to be equivalent(等价的).

However, if either x or y is NULL, then the first IF statement assigns the value of y to high and the second IF statement assigns the value of x to high.

Example 2–40 NOT NULL Equals NULL

DECLARE

x INTEGER := 2;

Y INTEGER := 5;

high INTEGER;

BEGIN

IF (x > y) -- If x or y is NULL, then (x > y) is NULL

THEN high := x; -- run if (x > y) is TRUE

ELSE high := y; -- run if (x > y) is FALSE or NULL

END IF;

IF NOT (x > y) -- If x or y is NULL, then NOT (x > y) is NULL

THEN high := y; -- run if NOT (x > y) is TRUE

ELSE high := x; -- run if NOT (x > y) is FALSE or NULL

END IF;

END;

/Example 2–41 invokes the print_boolean procedure from Example 2–35 three times.

The third and first invocation are logically equivalent—the parentheses in the third invocation only improve readability. The parentheses in the second invocation change the order of operation.

Example 2–41 Changing Evaluation Order of Logical Operators

DECLARE

x BOOLEAN := FALSE;

y BOOLEAN := FALSE;

BEGIN

print_boolean ('NOT x AND y', NOT x AND y);

print_boolean ('NOT (x AND y)', NOT (x AND y));

print_boolean ('(NOT x) AND y', (NOT x) AND y);

END;

/Result:

NOT x AND y = FALSE

NOT (x AND y) = TRUE

(NOT x) AND y = FALSEShort-Circuit Evaluation

When evaluating a logical expression, PL/SQL uses short-circuit evaluation.

That is, PL/SQL stops evaluating the expression as soon as it can determine the result.

Therefore, you can write expressions that might otherwise cause errors.

In Example 2–42, short-circuit evaluation prevents the OR expression from causing a divide-by-zero error.

When the value of on_hand is zero, the value of the left operand is TRUE, so PL/SQL does not evaluate the right operand.

If PL/SQL evaluated both operands before applying the OR operator, the right operand would cause a **division by

zero** error.

Example 2–42 Short-Circuit Evaluation

DECLARE

on_hand INTEGER := 0;

on_order INTEGER := 100;

BEGIN

-- Does not cause divide-by-zero error;

-- evaluation stops after first expression

IF (on_hand = 0) OR ((on_order / on_hand) < 5) THEN

DBMS_OUTPUT.PUT_LINE('On hand quantity is zero.');

END IF;

END;

/Result:

On hand quantity is zero.

2985

2985

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?