吴恩达Coursera课程 DeepLearning.ai 编程作业系列,本文为《改善深层神经网络:超参数调试、正则化以及优化 》部分的第四周“深度学习的实践方面”的课程作业,同时增加了一些辅助的测试函数。

另外,本节课程笔记在此:《 吴恩达Coursera深度学习课程 DeepLearning.ai 提炼笔记(2-1)– 深度学习的实践方面》,如有任何建议和问题,欢迎留言。

You can get the support code and datasets from here for all the following parts.

Part 1:Initialization

A well chosen initialization can:

- Speed up the convergence of gradient descent

- Increase the odds of gradient descent converging to a lower training (and generalization) error

To get started, run the following cell to load the packages and the planar dataset you will try to classify.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import sklearn

import sklearn.datasets

from init_utils import sigmoid, relu, compute_loss, forward_propagation, backward_propagation

from init_utils import update_parameters, predict, load_dataset, plot_decision_boundary, predict_dec

%matplotlib inline

plt.rcParams['figure.figsize'] = (7.0, 4.0) # set default size of plots

plt.rcParams['image.interpolation'] = 'nearest'

plt.rcParams['image.cmap'] = 'gray'

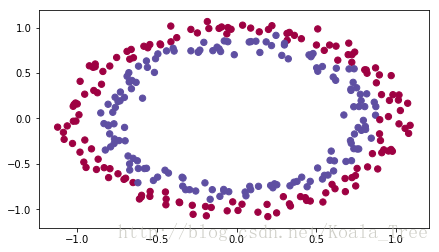

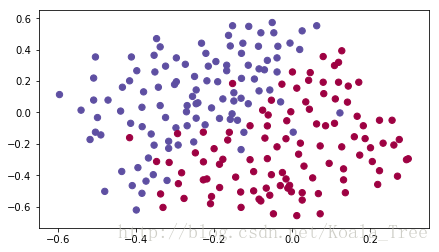

# load image dataset: blue/red dots in circles

train_X, train_Y, test_X, test_Y = load_dataset()

There are some import function:

def sigmoid(x):

"""

Compute the sigmoid of x

Arguments:

x -- A scalar or numpy array of any size.

Return:

s -- sigmoid(x)

"""

s = 1/(1+np.exp(-x))

return s

def relu(x):

"""

Compute the relu of x

Arguments:

x -- A scalar or numpy array of any size.

Return:

s -- relu(x)

"""

s = np.maximum(0,x)

return s

def compute_loss(a3, Y):

"""

Implement the loss function

Arguments:

a3 -- post-activation, output of forward propagation

Y -- "true" labels vector, same shape as a3

Returns:

loss - value of the loss function

"""

m = Y.shape[1]

logprobs = np.multiply(-np.log(a3),Y) + np.multiply(-np.log(1 - a3), 1 - Y)

loss = 1./m * np.nansum(logprobs)

return loss

def forward_propagation(X, parameters):

"""

Implements the forward propagation (and computes the loss) presented in Figure 2.

Arguments:

X -- input dataset, of shape (input size, number of examples)

Y -- true "label" vector (containing 0 if cat, 1 if non-cat)

parameters -- python dictionary containing your parameters "W1", "b1", "W2", "b2", "W3", "b3":

W1 -- weight matrix of shape ()

b1 -- bias vector of shape ()

W2 -- weight matrix of shape ()

b2 -- bias vector of shape ()

W3 -- weight matrix of shape ()

b3 -- bias vector of shape ()

Returns:

loss -- the loss function (vanilla logistic loss)

"""

# retrieve parameters

W1 = parameters["W1"]

b1 = parameters["b1"]

W2 = parameters["W2"]

b2 = parameters["b2"]

W3 = parameters["W3"]

b3 = parameters["b3"]

# LINEAR -> RELU -> LINEAR -> RELU -> LINEAR -> SIGMOID

z1 = np.dot(W1, X) + b1

a1 = relu(z1)

z2 = np.dot(W2, a1) + b2

a2 = relu(z2)

z3 = np.dot(W3, a2) + b3

a3 = sigmoid(z3)

cache = (z1, a1, W1, b1, z2, a2, W2, b2, z3, a3, W3, b3)

return a3, cache

def backward_propagation(X, Y, cache):

"""

Implement the backward propagation presented in figure 2.

Arguments:

X -- input dataset, of shape (input size, number of examples)

Y -- true "label" vector (containing 0 if cat, 1 if non-cat)

cache -- cache output from forward_propagation()

Returns:

gradients -- A dictionary with the gradients with respect to each parameter, activation and pre-activation variables

"""

m = X.shape[1]

(z1, a1, W1, b1, z2, a2, W2, b2, z3, a3, W3, b3) = cache

dz3 = 1./m * (a3 - Y)

dW3 = np.dot(dz3, a2.T)

db3 = np.sum(dz3, axis=1, keepdims = True)

da2 = np.dot(W3.T, dz3)

dz2 = np.multiply(da2, np.int64(a2 > 0))

dW2 = np.dot(dz2, a1.T)

db2 = np.sum(dz2, axis=1, keepdims = True)

da1 = np.dot(W2.T, dz2)

dz1 = np.multiply(da1, np.int64(a1 > 0))

dW1 = np.dot(dz1, X.T)

db1 = np.sum(dz1, axis=1, keepdims = True)

gradients = {

"dz3": dz3, "dW3": dW3, "db3": db3,

"da2": da2, "dz2": dz2, "dW2": dW2, "db2": db2,

"da1": da1, "dz1": dz1, "dW1": dW1, "db1": db1}

return gradients

def update_parameters(parameters, grads, learning_rate):

"""

Update parameters using gradient descent

Arguments:

parameters -- python dictionary containing your parameters

grads -- python dictionary containing your gradients, output of n_model_backward

Returns:

parameters -- python dictionary containing your updated parameters

parameters['W' + str(i)] = ...

parameters['b' + str(i)] = ...

"""

L = len(parameters) // 2 # number of layers in the neural networks

# Update rule for each parameter

for k in range(L):

parameters["W" + str(k+1)] = parameters["W" + str(k+1)] - learning_rate * grads["dW" + str(k+1)]

parameters["b" + str(k+1)] = parameters["b" + str(k+1)] - learning_rate * grads["db" + str(k+1)]

return parameters

def predict(X, y, parameters):

"""

This function is used to predict the results of a n-layer neural network.

Arguments:

X -- data set of examples you would like to label

parameters -- parameters of the trained model

Returns:

p -- predictions for the given dataset X

"""

m = X.shape[1]

p = np.zeros((1,m), dtype = np.int)

# Forward propagation

a3, caches = forward_propagation(X, parameters)

# convert probas to 0/1 predictions

for i in range(0, a3.shape[1]):

if a3[0,i] > 0.5:

p[0,i] = 1

else:

p[0,i] = 0

# print results

print("Accuracy: " + str(np.mean((p[0,:] == y[0,:]))))

return p

def load_dataset():

np.random.seed(1)

train_X, train_Y = sklearn.datasets.make_circles(n_samples=300, noise=.05)

np.random.seed(2)

test_X, test_Y = sklearn.datasets.make_circles(n_samples=100, noise=.05)

# Visualize the data

plt.scatter(train_X[:, 0], train_X[:, 1], c=train_Y, s=40, cmap=plt.cm.Spectral);

train_X = train_X.T

train_Y = train_Y.reshape((1, train_Y.shape[0]))

test_X = test_X.T

test_Y = test_Y.reshape((1, test_Y.shape[0]))

return train_X, train_Y, test_X, test_Y

def plot_decision_boundary(model, X, y):

# Set min and max values and give it some padding

x_min, x_max = X[0, :].min() - 1, X[0, :].max() + 1

y_min, y_max = X[1, :].min() - 1, X[1, :].max() + 1

h = 0.01

# Generate a grid of points with distance h between them

xx, yy = np.meshgrid(np.arange(x_min, x_max, h), np.arange(y_min, y_max, h))

# Predict the function value for the whole grid

Z = model(np.c_[xx.ravel(), yy.ravel()])

Z = Z.reshape(xx.shape)

# Plot the contour and training examples

plt.contourf(xx, yy, Z, cmap=plt.cm.Spectral)

plt.ylabel('x2')

plt.xlabel('x1')

plt.scatter(X[0, :], X[1, :], c=y, cmap=plt.cm.Spectral)

plt.show()

def predict_dec(parameters, X):

"""

Used for plotting decision boundary.

Arguments:

parameters -- python dictionary containing your parameters

X -- input data of size (m, K)

Returns

predictions -- vector of predictions of our model (red: 0 / blue: 1)

"""

# Predict using forward propagation and a classification threshold of 0.5

a3, cache = forward_propagation(X, parameters)

predictions = (a3>0.5)

return predictionsYou would like a classifier to separate the blue dots from the red dots.

1 - Neural Network model

You will use a 3-layer neural network (already implemented for you). Here are the initialization methods you will experiment with:

- Zeros initialization – setting initialization = "zeros" in the input argument.

- Random initialization – setting initialization = "random" in the input argument. This initializes the weights to large random values.

- He initialization – setting initialization = "he" in the input argument. This initializes the weights to random values scaled according to a paper by He et al., 2015.

Instructions: Please quickly read over the code below, and run it. In the next part you will implement the three initialization methods that this model() calls.

def model(X, Y, learning_rate = 0.01, num_iterations = 15000, print_cost = True, initialization = "he"):

"""

Implements a three-layer neural network: LINEAR->RELU->LINEAR->RELU->LINEAR->SIGMOID.

Arguments:

X -- input data, of shape (2, number of examples)

Y -- true "label" vector (containing 0 for red dots; 1 for blue dots), of shape (1, number of examples)

learning_rate -- learning rate for gradient descent

num_iterations -- number of iterations to run gradient descent

print_cost -- if True, print the cost every 1000 iterations

initialization -- flag to choose which initialization to use ("zeros","random" or "he")

Returns:

parameters -- parameters learnt by the model

"""

grads = {}

costs = [] # to keep track of the loss

m = X.shape[1] # number of examples

layers_dims = [X.shape[0], 10, 5, 1]

# Initialize parameters dictionary.

if initialization == "zeros":

parameters = initialize_parameters_zeros(layers_dims)

elif initialization == "random":

parameters = initialize_parameters_random(layers_dims)

elif initialization == "he":

parameters = initialize_parameters_he(layers_dims)

# Loop (gradient descent)

for i in range(0, num_iterations):

# Forward propagation: LINEAR -> RELU -> LINEAR -> RELU -> LINEAR -> SIGMOID.

a3, cache = forward_propagation(X, parameters)

# Loss

cost = compute_loss(a3, Y)

# Backward propagation.

grads = backward_propagation(X, Y, cache)

# Update parameters.

parameters = update_parameters(parameters, grads, learning_rate)

# Print the loss every 1000 iterations

if print_cost and i % 1000 == 0:

print("Cost after iteration {}: {}".format(i, cost))

costs.append(cost)

# plot the loss

plt.plot(costs)

plt.ylabel('cost')

plt.xlabel('iterations (per hundreds)')

plt.title("Learning rate =" + str(learning_rate))

plt.show()

return parameters2 - Zero initialization

There are two types of parameters to initialize in a neural network:

- the weight matrices (W[1],W[2],W[3],...,W[L−1],W[L]) ( W [ 1 ] , W [ 2 ] , W [ 3 ] , . . . , W [ L − 1 ] , W [ L ] )

- the bias vectors (b[1],b[2],b[3],...,b[L−1],b[L]) ( b [ 1 ] , b [ 2 ] , b [ 3 ] , . . . , b [ L − 1 ] , b [ L ] )

Exercise: Implement the following function to initialize all parameters to zeros. You’ll see later that this does not work well since it fails to “break symmetry”, but lets try it anyway and see what happens. Use np.zeros((..,..)) with the correct shapes.

# GRADED FUNCTION: initialize_parameters_zeros

def initialize_parameters_zeros(layers_dims):

"""

Arguments:

layer_dims -- python array (list) containing the size of each layer.

Returns:

parameters -- python dictionary containing your parameters "W1", "b1", ..., "WL", "bL":

W1 -- weight matrix of shape (layers_dims[1], layers_dims[0])

b1 -- bias vector of shape (layers_dims[1], 1)

...

WL -- weight matrix of shape (layers_dims[L], layers_dims[L-1])

bL -- bias vector of shape (layers_dims[L], 1)

"""

parameters = {}

L = len(layers_dims) # number of layers in the network

for l in range(1, L):

### START CODE HERE ### (≈ 2 lines of code)

parameters['W' + str(l)] = np.zeros((layers_dims[l],layers_dims[l-1]))

parameters['b' + str(l)] = np.zeros((layers_dims[l],1))

### END CODE HERE ###

return parametersparameters = initialize_parameters_zeros([3,2,1])

print("W1 = " + str(parameters["W1"]))

print("b1 = " + str(parameters["b1"]))

print("W2 = " + str(parameters["W2"]))

print("b2 = " + str(parameters["b2"]))W1 = [[ 0. 0. 0.]

[ 0. 0. 0.]]

b1 = [[ 0.]

[ 0.]]

W2 = [[ 0. 0.]]

b2 = [[ 0.]]

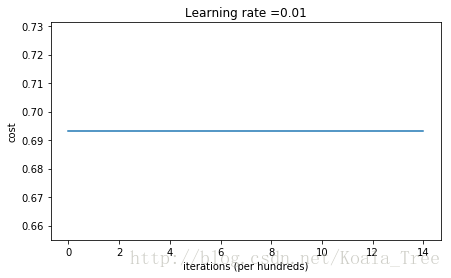

Run the following code to train your model on 15,000 iterations using zeros initialization.

parameters = model(train_X, train_Y, initialization = "zeros")

print ("On the train set:")

predictions_train = predict(train_X, train_Y, parameters)

print ("On the test set:")

predictions_test = predict(test_X, test_Y, parameters)Cost after iteration 0: 0.6931471805599453

Cost after iteration 1000: 0.6931471805599453

Cost after iteration 2000: 0.6931471805599453

Cost after iteration 3000: 0.6931471805599453

Cost after iteration 4000: 0.6931471805599453

Cost after iteration 5000: 0.6931471805599453

Cost after iteration 6000: 0.6931471805599453

Cost after iteration 7000: 0.6931471805599453

Cost after iteration 8000: 0.6931471805599453

Cost after iteration 9000: 0.6931471805599453

Cost after iteration 10000: 0.6931471805599455

Cost after iteration 11000: 0.6931471805599453

Cost after iteration 12000: 0.6931471805599453

Cost after iteration 13000: 0.6931471805599453

Cost after iteration 14000: 0.6931471805599453

On the train set:

Accuracy: 0.5

On the test set:

Accuracy: 0.5

The performance is really bad, and the cost does not really decrease, and the algorithm performs no better than random guessing. Why? Lets look at the details of the predictions and the decision boundary:

print ("predictions_train = " + str(predictions_train))

print ("predictions_test = " + str(predictions_test))predictions_train = [[0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0]]

predictions_test = [[0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0]]

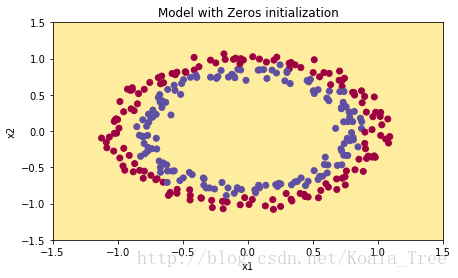

plt.title("Model with Zeros initialization")

axes = plt.gca()

axes.set_xlim([-1.5,1.5])

axes.set_ylim([-1.5,1.5])

plot_decision_boundary(lambda x: predict_dec(parameters, x.T), train_X, train_Y)

The model is predicting 0 for every example.

In general, initializing all the weights to zero results in the network failing to break symmetry. This means that every neuron in each layer will learn the same thing, and you might as well be training a neural network with n[l]=1 n [ l ] = 1 for every layer, and the network is no more powerful than a linear classifier such as logistic regression.

What you should remember:

- The weights W[l] W [ l ] should be initialized randomly to break symmetry.

- It is however okay to initialize the biases b[l] b [ l ] to zeros. Symmetry is still broken so long as W[l] W [ l ] is initialized randomly.

3 - Random initialization

To break symmetry, lets intialize the weights randomly. Following random initialization, each neuron can then proceed to learn a different function of its inputs. In this exercise, you will see what happens if the weights are intialized randomly, but to very large values.

Exercise: Implement the following function to initialize your weights to large random values (scaled by *10) and your biases to zeros. Use np.random.randn(..,..) * 10 for weights and np.zeros((.., ..)) for biases. We are using a fixed np.random.seed(..) to make sure your “random” weights match ours, so don’t worry if running several times your code gives you always the same initial values for the parameters.

# GRADED FUNCTION: initialize_parameters_random

def initialize_parameters_random(layers_dims):

"""

Arguments:

layer_dims -- python array (list) containing the size of each layer.

Returns:

parameters -- python dictionary containing your parameters "W1", "b1", ..., "WL", "bL":

W1 -- weight matrix of shape (layers_dims[1], layers_dims[0])

b1 -- bias vector of shape (layers_dims[1], 1)

...

WL -- weight matrix of shape (layers_dims[L], layers_dims[L-1])

bL -- bias vector of shape (layers_dims[L], 1)

"""

np.random.seed(3) # This seed makes sure your "random" numbers will be the as ours

parameters = {}

L = len(layers_dims) # integer representing the number of layers

for l in range(1, L):

### START CODE HERE ### (≈ 2 lines of code)

parameters['W' + str(l)] = np.random.randn(layers_dims[l],layers_dims[l-1])*10

parameters['b' + str(l)] = np.zeros((layers_dims[l],1))

### END CODE HERE ###

return parametersparameters = initialize_parameters_random([3, 2, 1])

print("W1 = " + str(parameters["W1"]))

print("b1 = " + str(parameters["b1"]))

print("W2 = " + str(parameters["W2"]))

print("b2 = " + str(parameters["b2"]))W1 = [[ 17.88628473 4.36509851 0.96497468]

[-18.63492703 -2.77388203 -3.54758979]]

b1 = [[ 0.]

[ 0.]]

W2 = [[-0.82741481 -6.27000677]]

b2 = [[ 0.]]

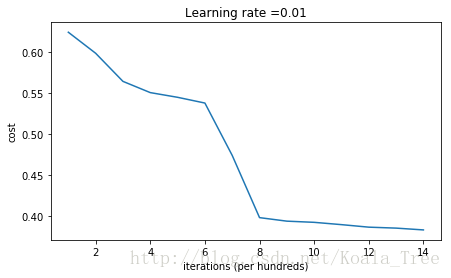

Run the following code to train your model on 15,000 iterations using random initialization.

parameters = model(train_X, train_Y, initialization = "random")

print ("On the train set:")

predictions_train = predict(train_X, train_Y, parameters)

print ("On the test set:")

predictions_test = predict(test_X, test_Y, parameters)Cost after iteration 0: inf

Cost after iteration 1000: 0.6237287551108738

Cost after iteration 2000: 0.5981106708339466

Cost after iteration 3000: 0.5638353726276827

Cost after iteration 4000: 0.550152614449184

Cost after iteration 5000: 0.5444235275228304

Cost after iteration 6000: 0.5374184054630083

Cost after iteration 7000: 0.47357131493578297

Cost after iteration 8000: 0.39775634899580387

Cost after iteration 9000: 0.3934632865981078

Cost after iteration 10000: 0.39202525076484457

Cost after iteration 11000: 0.38921493051297673

Cost after iteration 12000: 0.38614221789840486

Cost after iteration 13000: 0.38497849983013926

Cost after iteration 14000: 0.38278397192120406

On the train set:

Accuracy: 0.83

On the test set:

Accuracy: 0.86

If you see “inf” as the cost after the iteration 0, this is because of numerical roundoff; a more numerically sophisticated implementation would fix this. But this isn’t worth worrying about for our purposes.

Anyway, it looks like you have broken symmetry, and this gives better results. than before. The model is no longer outputting all 0s.

print (predictions_train)

print (predictions_test)[[1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1

1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0

0 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1

1 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 0

1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1

0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 1

0 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 0 1

1 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1

1 1 1 0]]

[[1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 1 0

1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 1 1

1 1 1 0 1 0 0 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 1 0 0]]

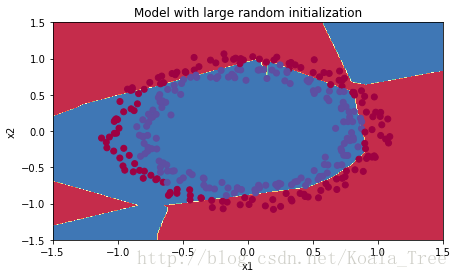

plt.title("Model with large random initialization")

axes = plt.gca()

axes.set_xlim([-1.5,1.5])

axes.set_ylim([-1.5,1.5])

plot_decision_boundary(lambda x: predict_dec(parameters, x.T), train_X, train_Y)

Observations:

- The cost starts very high. This is because with large random-valued weights, the last activation (sigmoid) outputs results that are very close to 0 or 1 for some examples, and when it gets that example wrong it incurs a very high loss for that example. Indeed, when log(a[3])=log(0) log ( a [ 3 ] ) = log ( 0 ) , the loss goes to infinity.

- Poor initialization can lead to vanishing/exploding gradients, which also slows down the optimization algorithm.

- If you train this network longer you will see better results, but initializing with overly large random numbers slows down the optimization.

In summary:

- Initializing weights to very large random values does not work well.

- Hopefully intializing with small random values does better. The important question is: how small should be these random values be? Lets find out in the next part!

4 - He initialization

Finally, try “He Initialization”; this is named for the first author of He et al., 2015. (If you have heard of “Xavier initialization”, this is similar except Xavier initialization uses a scaling factor for the weights W[l] W [ l ] of sqrt(1./layers_dims[l-1]) where He initialization would use sqrt(2./layers_dims[l-1]).)

Exercise: Implement the following function to initialize your parameters with He initialization.

Hint: This function is similar to the previous initialize_parameters_random(...). The only difference is that instead of multiplying np.random.randn(..,..) by 10, you will multiply it by 2dimension of the previous layer−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−−√ 2 dimension of the previous layer , which is what He initialization recommends for layers with a ReLU activation.

# GRADED FUNCTION: initialize_parameters_he

def initialize_parameters_he(layers_dims):

"""

Arguments:

layer_dims -- python array (list) containing the size of each layer.

Returns:

parameters -- python dictionary containing your parameters "W1", "b1", ..., "WL", "bL":

W1 -- weight matrix of shape (layers_dims[1], layers_dims[0])

b1 -- bias vector of shape (layers_dims[1], 1)

...

WL -- weight matrix of shape (layers_dims[L], layers_dims[L-1])

bL -- bias vector of shape (layers_dims[L], 1)

"""

np.random.seed(3)

parameters = {}

L = len(layers_dims) - 1 # integer representing the number of layers

for l in range(1, L + 1):

### START CODE HERE ### (≈ 2 lines of code)

parameters['W' + str(l)] = np.random.randn(layers_dims[l],layers_dims[l-1])*np.sqrt(2./layers_dims[l-1])

parameters['b' + str(l)] = np.zeros((layers_dims[l],1))

### END CODE HERE ###

return parametersparameters = initialize_parameters_he([2, 4, 1])

print("W1 = " + str(parameters["W1"]))

print("b1 = " + str(parameters["b1"]))

print("W2 = " + str(parameters["W2"]))

print("b2 = " + str(parameters["b2"]))W1 = [[ 1.78862847 0.43650985]

[ 0.09649747 -1.8634927 ]

[-0.2773882 -0.35475898]

[-0.08274148 -0.62700068]]

b1 = [[ 0.]

[ 0.]

[ 0.]

[ 0.]]

W2 = [[-0.03098412 -0.33744411 -0.92904268 0.62552248]]

b2 = [[ 0.]]

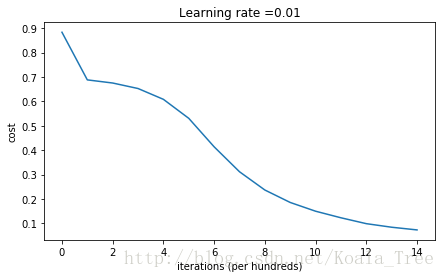

Run the following code to train your model on 15,000 iterations using He initialization.

parameters = model(train_X, train_Y, initialization = "he")

print ("On the train set:")

predictions_train = predict(train_X, train_Y, parameters)

print ("On the test set:")

predictions_test = predict(test_X, test_Y, parameters)Cost after iteration 0: 0.8830537463419761

Cost after iteration 1000: 0.6879825919728063

Cost after iteration 2000: 0.6751286264523371

Cost after iteration 3000: 0.6526117768893807

Cost after iteration 4000: 0.6082958970572938

Cost after iteration 5000: 0.5304944491717495

Cost after iteration 6000: 0.4138645817071794

Cost after iteration 7000: 0.3117803464844441

Cost after iteration 8000: 0.23696215330322562

Cost after iteration 9000: 0.18597287209206836

Cost after iteration 10000: 0.1501555628037182

Cost after iteration 11000: 0.12325079292273548

Cost after iteration 12000: 0.09917746546525937

Cost after iteration 13000: 0.0845705595402428

Cost after iteration 14000: 0.07357895962677366

On the train set:

Accuracy: 0.993333333333

On the test set:

Accuracy: 0.96

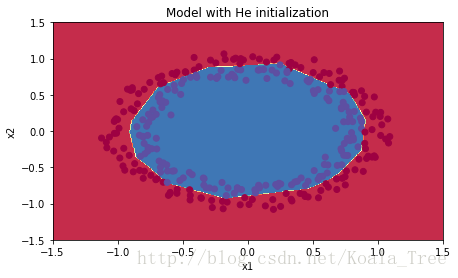

plt.title("Model with He initialization")

axes = plt.gca()

axes.set_xlim([-1.5,1.5])

axes.set_ylim([-1.5,1.5])

plot_decision_boundary(lambda x: predict_dec(parameters, x.T), train_X, train_Y)

Observations:

- The model with He initialization separates the blue and the red dots very well in a small number of iterations.

5 - Conclusions

You have seen three different types of initializations. For the same number of iterations and same hyperparameters the comparison is:

| **Model** | **Train accuracy** | **Problem/Comment** |

| 3-layer NN with zeros initialization | 50% | fails to break symmetry |

| 3-layer NN with large random initialization | 83% | too large weights |

| 3-layer NN with He initialization | 99% | recommended method |

What you should remember from this notebook:

- Different initializations lead to different results

- Random initialization is used to break symmetry and make sure different hidden units can learn different things

- Don’t intialize to values that are too large

- He initialization works well for networks with ReLU activations.

Part 2:Regularization

Let’s first import the packages you are going to use.

# import packages

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from reg_utils import sigmoid, relu, plot_decision_boundary, initialize_parameters, load_2D_dataset, predict_dec

from reg_utils import compute_cost, predict, forward_propagation, backward_propagation, update_parameters

import sklearn

import sklearn.datasets

import scipy.io

from testCases import *

%matplotlib inline

plt.rcParams['figure.figsize'] = (7.0, 4.0) # set default size of plots

plt.rcParams['image.interpolation'] = 'nearest'

plt.rcParams['image.cmap'] = 'gray'There are some function iported:

def initialize_parameters(layer_dims):

"""

Arguments:

layer_dims -- python array (list) containing the dimensions of each layer in our network

Returns:

parameters -- python dictionary containing your parameters "W1", "b1", ..., "WL", "bL":

W1 -- weight matrix of shape (layer_dims[l], layer_dims[l-1])

b1 -- bias vector of shape (layer_dims[l], 1)

Wl -- weight matrix of shape (layer_dims[l-1], layer_dims[l])

bl -- bias vector of shape (1, layer_dims[l])

Tips:

- For example: the layer_dims for the "Planar Data classification model" would have been [2,2,1].

This means W1's shape was (2,2), b1 was (1,2), W2 was (2,1) and b2 was (1,1). Now you have to generalize it!

- In the for loop, use parameters['W' + str(l)] to access Wl, where l is the iterative integer.

"""

np.random.seed(3)

parameters = {}

L = len(layer_dims) # number of layers in the network

for l in range(1, L):

parameters['W' + str(l)] = np.random.randn(layer_dims[l], layer_dims[l-1]) / np.sqrt(layer_dims[l-1])

parameters['b' + str(l)] = np.zeros((layer_dims[l], 1))

assert(parameters['W' + str(l)].shape == layer_dims[l], layer_dims[l-1])

assert(parameters['W' + str(l)].shape == layer_dims[l], 1)

return parameters

def compute_cost(a3, Y):

"""

Implement the cost function

Arguments:

a3 -- post-activation, output of forward propagation

Y -- "true" labels vector, same shape as a3

Returns:

cost - value of the cost function

"""

m = Y.shape[1]

logprobs = np.multiply(-np.log(a3),Y) + np.multiply(-np.log(1 - a3), 1 - Y)

cost = 1./m * np.nansum(logprobs)

return cost

def load_2D_dataset():

data = scipy.io.loadmat('datasets/data.mat')

train_X = data['X'].T

train_Y = data['y'].T

test_X = data['Xval'].T

test_Y = data['yval'].T

plt.scatter(train_X[0, :], train_X[1, :], c=train_Y, s=40, cmap=plt.cm.Spectral);

return train_X, train_Y, test_X, test_YThe data set in load_2D_dataset() ,you can get it in the address : http://pan.baidu.com/s/1sl4YzfB . If the link is invalid , please leave your message in the message area.

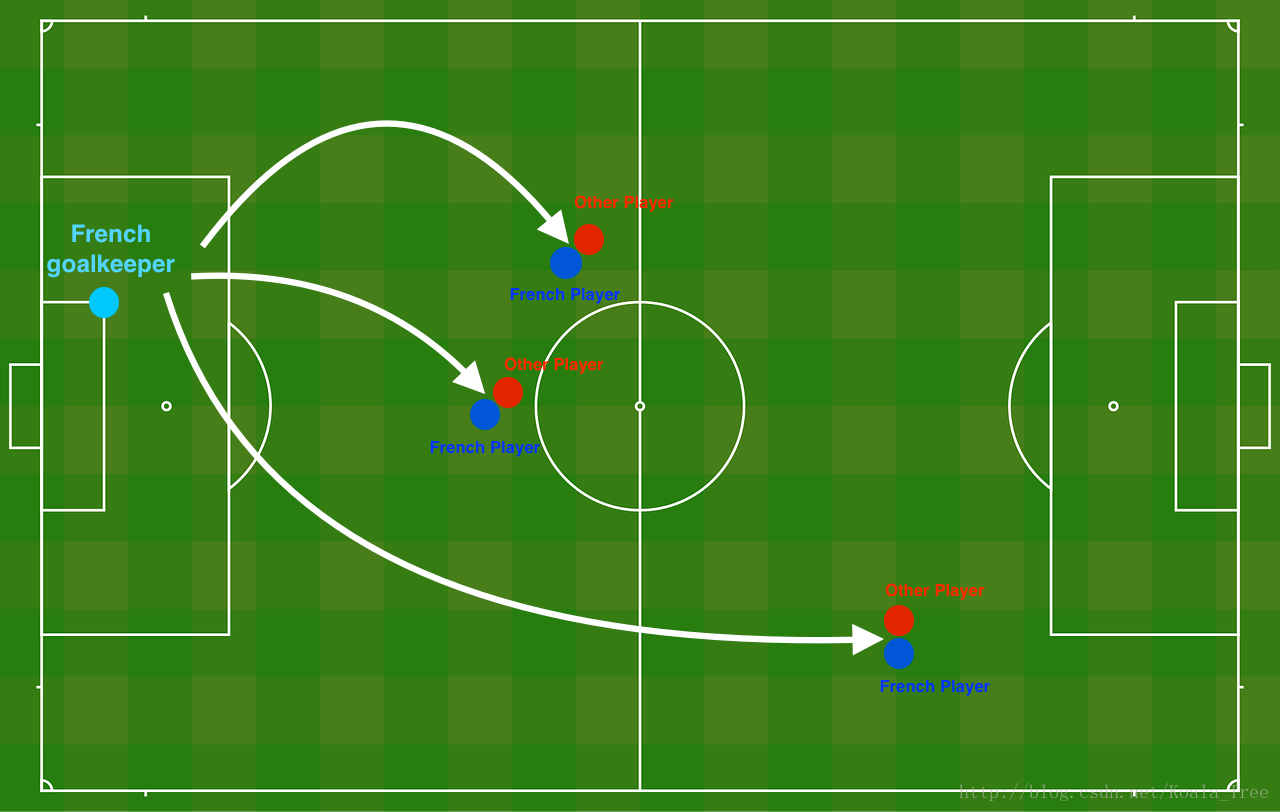

Problem Statement: You have just been hired as an AI expert by the French Football Corporation. They would like you to recommend positions where France’s goal keeper should kick the ball so that the French team’s players can then hit it with their head.

The goal keeper kicks the ball in the air, the players of each team are fighting to hit the ball with their head

They give you the following 2D dataset from France’s past 10 games.

train_X, train_Y, test_X, test_Y = load_2D_dataset()

Each dot corresponds to a position on the football field where a football player has hit the ball with his/her head after the French goal keeper has shot the ball from the left side of the football field.

- If the dot is blue, it means the French player managed to hit the ball with his/her head

- If the dot is red, it means the other team’s player hit the ball with their head

Your goal: Use a deep learning model to find the positions on the field where the goalkeeper should kick the ball.

Analysis of the dataset: This dataset is a little noisy, but it looks like a diagonal line separating the upper left half (blue) from the lower right half (red) would work well.

You will first try a non-regularized model. Then you’ll

最低0.47元/天 解锁文章

最低0.47元/天 解锁文章

277

277

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?