HFACS(人因分析与分类系统)

1 来源

人的因素分析与分类系统(Human Factors Analysis and Classification System, HFACS)是基于Reason的瑞士奶酪模型提出的,它细化了各层内容。

该模型是Scott Shappell和Douglas A Wiegmann两人著作,由Office of Aviation Medicine Washington, DC(美国华盛顿特区航空医学办公室)发布,受U.S. Department of Transportation(美国运输部)赞助。

HFACS最早主要应用于航空事故分析,后经学者们修改,也应用于航海事故、煤矿事故、电力事故等的分析中, HFACS各层内容未做精确定义,原因因素依靠人为列举,影响了其在更广阔领域的应用。

2 拟解决的问题(背景)

70%到80%的民用和军用航空事故都与人为失误有关。然而,大多数事故报告系统并没有围绕任何人为错误的理论框架设计。因此,大多数事故数据库都不利于传统的人为错误分析,使得干预策略的确定十分繁琐。所需要的是一个普遍的人为错误框架,可以围绕它设计新的调查方法,并重组现有的事故数据库。

Human error has been implicated in 70 to 80% of all civil and military aviation accidents. Yet, most accident reporting systems are not designed around any theoretical framework of human error. As a result, most accident databases are not conducive to a traditional human error analysis, making the identification of intervention strategies onerous. What is required is a general human error framework around which new investigative methods can be designed and existing accident databases restructured.

那么,文献中反复提到的70- 80%的人为错误到底是由什么构成的呢?有些人会让我们相信,人为错误和“飞行员”错误是同义词。然而,简单地将航空事故仅仅归咎于飞行员的失误,是一种过于简单,甚至是幼稚的事故起因分析方法。毕竟,众所周知,事故不能归咎于单一原因,或者在大多数情况下,甚至不能归咎于单个人(Heinrich, Petersen, and Roos, 1980)。事实上,即使是确定一个“主要”原因也充满了问题。相反,航空事故是许多原因的最终结果,只有最后一个是机组人员的不安全行为(Reason,1990;Shappell & Wiegmann, 1997a;Heinrich, Peterson, & Roos, 1980;Bird,1974)。

So what really constitutes that 70-80 % of human error repeatedly referred to in the literature? Some would have us believe that human error and “pilot” error are synonymous. Yet, simply writing off aviation accidents merely to pilot error is an overly simplistic, if not naive, approach to accident causation. After all, it is well established that accidents cannot be attributed to a single cause, or in most instances, even a single individual (Heinrich, Petersen, and Roos, 1980). In fact, even the identification of a “primary” cause is fraught with problems. Rather, aviation accidents are the end result of a number of causes, only the last of which are the unsafe acts of the aircrew (Reason, 1990; Shappell & Wiegmann, 1997a; Heinrich, Peterson, & Roos, 1980; Bird, 1974).

Reason人为错误的“瑞士奶酪”模型

Reason’s “Swiss Cheese” Model of Human Error

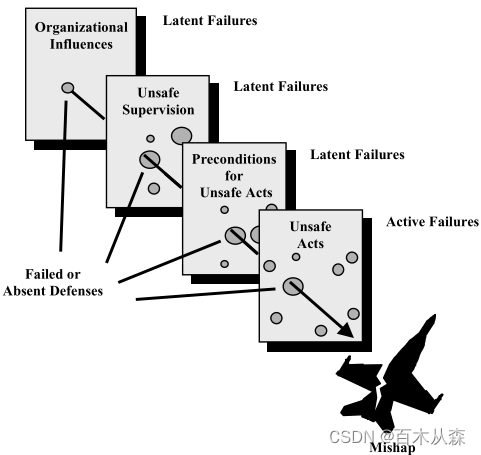

James Reason(1990)提出了一种特别吸引人的研究人为错误起源的方法。通常被称为人为错误的“瑞士奶酪”模型,原因描述了四个层次的人为错误,每一个都影响下一个(上图)。从事故往回看,第一个层次描述了那些最终导致事故的操作人员的不安全行为。在航空领域,这通常被称为机组人员/飞行员的错误,这是大多数事故调查工作的重点,因此,大多数原因都被发现。

James Reason(1990)提出了一种特别吸引人的研究人为错误起源的方法。通常被称为人为错误的“瑞士奶酪”模型,原因描述了四个层次的人为错误,每一个都影响下一个(上图)。从事故往回看,第一个层次描述了那些最终导致事故的操作人员的不安全行为。在航空领域,这通常被称为机组人员/飞行员的错误,这是大多数事故调查工作的重点,因此,大多数原因都被发现。

One particularly appealing approach to the genesis of human error is the one proposed by James Reason (1990). Generally referred to as the “Swiss cheese” model of human error, Reason describes four levels of human failure, each influencing the next (Figure 1). Working backwards in time from the accident, the first level depicts those Unsafe Acts of Operators that ulti mately led to the accident1. More commonly referred to in aviation as aircrew/pilot error, this level is where most accident investigations have focused their efforts and consequently, where most causal factors are uncovered.

然而,使“瑞士奶酪”模型在事故调查中特别有用的是,它迫使调查人员也在事件的因果序列中解决潜在的错误。 顾名思义,潜在错误与主动错误不同,可能潜伏或未被发现几个小时、几天、几周甚至更长时间,直到有一天它们对可疑的机组人员产生不利影响。 因此,即使是出于好意的调查人员也可能忽视它们。

However, what makes the “Swiss cheese” model particularly useful in accident investigation, is that it forces investigators to address latent failures within the causal sequence of events as well. As their name suggests, latent failures, unlike their active counterparts, may lie dormant or undetected for hours, days, weeks, or even longer, until one day they adversely affect the unsuspect ing aircrew. Consequently, they may be overlooked by investigators with even the best intentions.

在这个潜在错误的概念中,Reason又描述了三个层次的人类错误。首先涉及到机组人员的状况,因为它影响性能。这一水平被称为不安全行为的先决条件,包括精神疲劳、沟通和协调能力差等条件,通常被称为机组资源管理(CRM)。不足为奇的是,如果疲劳的机组人员不能与驾驶舱内的其他人或飞机以外的个人(如空中交通管制、维修等)沟通和协调他们的活动,就会做出糟糕的决定,并经常导致错误。

Within this concept of latent failures, Reason de scribed three more levels of human failure. The first involves the condition of the aircrew as it affects perfor mance. Referred to as Preconditions for Unsafe Acts, this level involves conditions such as mental fatigue and poor communication and coordination practices, often referred to as crew resource management (CRM). Not surprising, if fatigued aircrew fail to communicate and coordinate their activities with others in the cockpit or individuals external to the aircraft (e.g., air traffic con trol, maintenance, etc.), poor decisions are made and errors often result.

但是,究竟是什么原因导致沟通和协调在一开始就出现了问题呢?这也许就是Reason的工作与处理人为错误的更传统方法的不同之处。在许多情况下,良好的CRM实践的失败可以追溯到不安全监管的实例,这是人为失误的第三级。例如,如果两名缺乏经验(甚至可能低于平均水平的飞行员)的飞行员配对,在已知的恶劣天气的夜间飞行,有人真的会对悲剧的结果感到惊讶吗?更糟糕的是,如果这种有问题的人员配备,再加上缺乏高质量的客户关系管理培训,那么潜在的沟通错误,以及最终的机组人员错误,就会被放大。在某种意义上,机组人员被“设定”为失败,因为机组人员的协调和最终的性能将会受到损害。这并不是要减少机组人员所扮演的角色,只是说干预和缓解策略可能在系统中处于更高的位置。

But exactly why did communication and coordi nation break down in the first place? This is perhaps where Reason’s work departed from more traditional approaches to human error. In many instances, the breakdown in good CRM practices can be traced back to instances of Unsafe Supervision, the third level of human failure. If, for example, two inexperienced (and perhaps even below average pilots) are paired with each other and sent on a flight into known adverse weather at night, is anyone really surprised by a tragic outcome? To make matters worse, if this questionable manning practice is coupled with the lack of quality CRM training, the potential for mis communication and ultimately, aircrew errors, is magnified. In a sense then, the crew was “set up” for failure as crew coordination and ultimately perfor mance would be compromised. This is not to lessen the role played by the aircrew, only that intervention and mitigation strategies might lie higher within the system.

Reason模型也没有停留在监督层面;组织本身可以影响所有级别的绩效。例如,在财政紧缩时期,资金经常被削减,因此,训练和飞行时间被缩短。因此,主管常常别无选择,只能给“不熟练”的飞行员指派复杂的任务。因此,不足为奇的是,在缺乏良好的CRM培训的情况下,沟通和协调方面的失败就会开始出现,其他无数的先决条件也会出现,所有这些都会影响表现,并引发机组人员的错误。因此,如果要将事故率降低到目前的水平,调查人员和分析人员必须全面研究事故发生的顺序,并将其扩展到驾驶舱以外。最终,如果任何事故调查和预防系统要取得成功,就必须解决组织内各级的因果因素。

Reason’s model didn’t stop at the supervisory level either; the organization itself can impact perfor mance at all levels. For instance, in times of fiscal austerity, funding is often cut, and as a result, train ing and flight time are curtailed. Consequently, supervisors are often left with no alternative but to task “non-proficient” aviators with complex tasks. Not surprisingly then, in the absence of good CRM training, communication and coordination failures will begin to appear as will a myriad of other preconditions, all of which will affect performance and elicit aircrew errors. Therefore, it makes sense that, if the accident rate is going to be reduced beyond current levels, investigators and analysts alike must examine the accident sequence in its entirety and expand it beyond the cockpit. Ultimately, causal factors at all levels within the organization must be addressed if any accident investigation and prevention system is going to succeed.

在许多方面,Reason的“瑞士奶酪”事故因果关系模型已经彻底改变了对事故因果关系的普遍看法。然而,不幸的是,这只是一个理论,并没有详细说明如何在现实世界中应用它。换句话说,该理论从未定义过“奶酪上的洞”到底是什么,至少在日常操作的背景下是这样。最终,我们需要知道这些系统故障或“漏洞”是什么,以便在事故调查期间识别它们,或者更好的是,在事故发生之前检测和纠正它们。

In many ways, Reason’s “Swiss cheese” model of accident causation has revolutionized common views of accident causation. Unfortunately, however, it is simply a theory with few details on how to apply it in a real-world setting. In other words, the theory never defines what the “holes in the cheese” really are, at least within the context of everyday operations. Ulti mately, one needs to know what these system failures or “holes” are, so that they can be identified during accident investigations or better yet, detected and corrected before an accident occurs.

本文的重心将试图描述“奶酪上的洞”。然而,最初的框架(称为不安全操作分类)是利用从美国海军安全中心获得的300多起海军航空事故(Shappell & Wiegmann, 1997a),而不是试图使用很少或没有实际适用性的深奥理论来定义这些漏洞。最初的分类后来使用来自其他军方(美国陆军安全中心和美国空军安全中心)和民间组织(国家运输安全委员会和联邦航空管理局)的输入和数据进行了改进。其结果是人类因素分析和分类系统(HFACS)的发展。

The balance of this paper will attempt to describe the “holes in the cheese.” However, rather than attempt to define the holes using esoteric theories with little or no practical applicability, the original frame work (called the Taxonomy of Unsafe Operations) was developed using over 300 Naval aviation accidents obtained from the U.S. Naval Safety Center (Shappell & Wiegmann, 1997a). The original taxonomy has since been refined using input and data from other military (U.S. Army Safety Center and the U.S. Air Force Safety Center) and civilian organizations (National Transportation Safety Board and the Federal Aviation Administration). The result was the development of the Human Factors Analysis and Classification System (HFACS).

HFACS是基于美国海军安全中心300起航空事故确定“奶酪上的洞”,而且还使用了美国陆军安全中心和美国空军安全中心及民间组织的数据进行验证并改进。

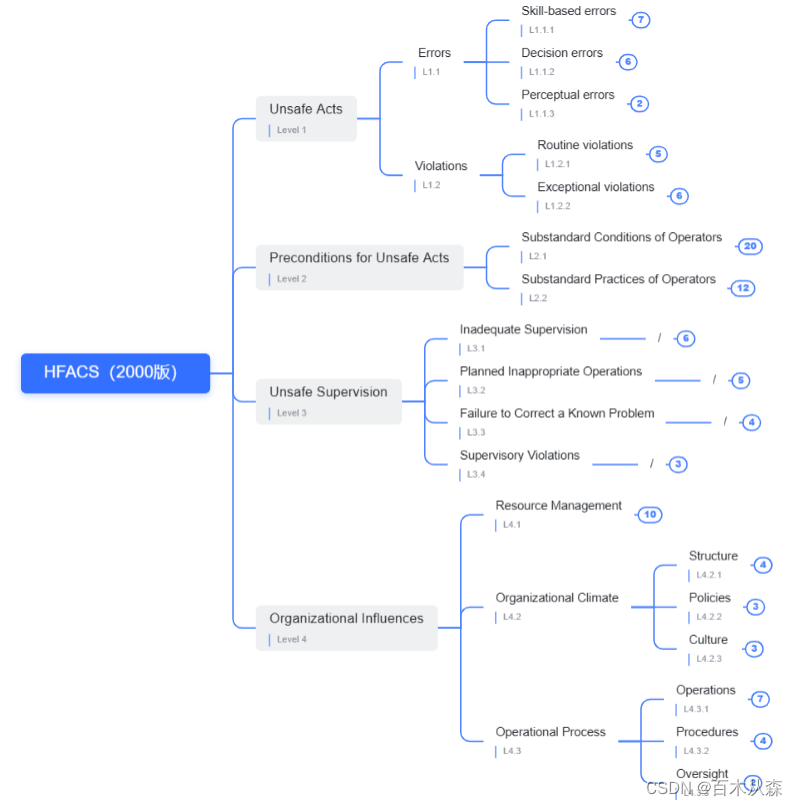

2 基本架构

HFACS借鉴了Reason(1990)关于潜在和主动失效的概念,描述了四个层面的失效:1)不安全行为(Unsafe Acts),2)不安全行为的前提条件(Preconditions for Unsafe Acts),3)不安全监督(Unsafe Supervision),4)组织影响(Organizational Influences)。下面简要说明主要组成部分和因果类别,从与事故最密切相关的水平开始,即不安全行为。

2.1 Unsafe Acts

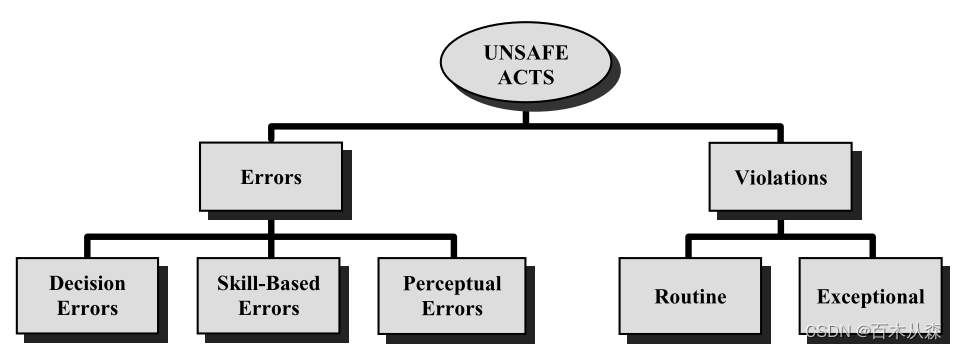

机组人员的不安全行为大致可以分为两类:失误和违规(Reason,1990)。一般来说,错误是指个体的精神或身体活动未能达到预期的结果。这并不奇怪,因为人类天生就会犯错,这些不安全行为主导了大多数事故数据库。另一方面,违反是指故意无视有关飞行安全的规则和条例。预测和预防这些令人恐惧的纯粹是“可预防的”不安全行为,这是许多组织的祸根,仍然是管理者和研究人员所无法做到的。

The unsafe acts of aircrew can be loosely classified into two categories: errors and violations (Reason, 1990). In general, errors represent the mental or physical activities of individuals that fail to achieve their intended outcome. Not surprising, given the fact that human beings by their very nature make errors, these unsafe acts dominate most accident databases. Violations, on the other hand, refer to the willful disregard for the rules and regulations that govern the safety of flight. The bane of many organizations, the prediction and prevention of these appalling and purely “preventable” unsafe acts, continue to elude managers and researchers alike.

尽管如此,区分错误和违规并不能提供大多数事故调查所需的粒度级别。因此,错误和违规的分类体系在这里得到了扩展(上图),就像其他地方一样(Reason,1990; Rasmussen,1982),包括三种基本的错误类型(技能型,决策型和感知型)和两种违规形式(常规和例外)。

Still, distinguishing between errors and violations does not provide the level of granularity required of most accident investigations. Therefore, the categories of errors and violations were expanded here (Figure 2), as elsewhere (Reason, 1990; Rasmussen, 1982), to include three basic error types (skill-based, decision, and perceptual) and two forms of violations (routine and exceptional).

2.1.1 Errors

2.1.1.1 Skill-based errors

基于技能的错误。在航空领域中,基于技能的行为最好被描述为“操纵杆和方向舵”以及其他基本的飞行技能,这些技能伴随着明显的有意识思维而发生。因此,这些基于技能的动作特别容易受到注意力和/或记忆力的故障的影响。事实上,注意力失败与许多基于技能的错误有关,例如视觉扫描模式的故障,任务固定,无意中激活控件,以及程序中步骤的错误排序等(下表)。一个典型的例子是,一架飞机的机组人员变得如此专注于故障排除烧毁的警告灯,以至于他们没有注意到他们致命的下降到地形。也许更接近家庭,考虑那些不幸的灵魂,他们把自己锁在车外或错过了出口,因为他要么分心,要么匆忙,要么做白日梦。这些都是高度自动化行为中经常发生的注意力失败的例子。不幸的是,当在家里或开车在城镇周围时,这些注意力/记忆力的失败可能会令人沮丧,在空中,它们可能会变成灾难性的。

Skill-based errors. Skill-based behavior within the context of aviation is best described as “stick-andrudder” and other basic flight skills that occur with out significant conscious thought. As a result, these skill-based actions are particularly vulnerable to fail ures of attention and/or memory. In fact, attention failures have been linked to many skill-based errors such as the breakdown in visual scan patterns, task fixation, the inadvertent activation of controls, and the misordering of steps in a procedure, among others (Table 1). A classic example is an aircraft’s crew that becomes so fixated on trouble-shooting a burned out warning light that they do not notice their fatal descent into the terrain. Perhaps a bit closer to home, consider the hapless soul who locks himself out of the car or misses his exit because he was either distracted, in a hurry, or daydreaming. These are both examples of attention failures that commonly occur during highly automatized behavior. Unfortunately, while at home or driving around town these attention/ memory failures may be frustrating, in the air they can become catastrophic.

与注意力缺失相反,记忆力缺失通常表现为清单中的遗漏项、位置丢失或忘记意图。例如,我们大多数人都经历过去冰箱只是忘记了我们去了。同样,不难想象,当在飞行紧急情况期间处于压力下时,可能会错过紧急程序中的关键步骤。然而,即使没有特别的压力,个人也忘记了在进近时设置襟翼或放下起落架-至少,这是一个令人尴尬的失态。

In contrast to attention failures, memory failures often appear as omitted items in a checklist, place losing, or forgotten intentions. For example, most of us have experienced going to the refrigerator only to forget what we went for. Likewise, it is not difficult to imagine that when under stress during inflight emergencies, critical steps in emergency procedures can be missed. However, even when not particularly stressed, individuals have forgotten to set the flaps on approach or lower the landing gear – at a minimum, an embarrassing gaffe.

第三种,也是最后一种,在许多事故调查中发现的基于技能的错误涉及技术错误。不管一个人的训练、经验和教育背景如何,一个人执行一系列特定事件的方式可能会有很大的不同。也就是说,具有相同训练、飞行等级和经验的两个飞行员在他们操纵飞机的方式上可能显著不同。当一个飞行员可以像翱翔的雄鹰一样优雅地平稳飞行时,其他人可能会像麻雀一样快速而粗糙地飞行。尽管如此,尽管两者都可能是安全的,同样擅长飞行,但它们采用的技术可能会使它们出现特定的故障模式。事实上,这些技术既是一个人的先天能力和天赋的因素,也是一个人个性的公开表达,这使得预防和减轻技术错误的努力充其量是困难的。

The third, and final, type of skill-based errors identified in many accident investigations involves technique errors. Regardless of one’s training, experience, and educational background, the manner in which one carries out a specific sequence of events may vary greatly. That is, two pilots with identical training, flight grades, and experience may differ significantly in the manner in which they maneuver their aircraft. While one pilot may fly smoothly with the grace of a soaring eagle, others may fly with the darting, rough transitions of a sparrow. Nevertheless, while both may be safe and equally adept at flying, the techniques they employ could set them up for specific failure modes. In fact, such techniques are as much a factor of innate ability and aptitude as they are an overt expression of one’s own personality, making efforts at the prevention and mitigation of technique errors difficult, at best.

2.1.1.2 Decision errors

第二种错误形式是决策错误,它代表的是有意的行为,按照预期进行,但计划被证明是不适当的或不适当的情况。这些不安全的行为通常被称为“最诚实的错误”,代表了“心在正确的地方”的个人的作为或不作为,但他们要么没有适当的知识,要么只是选择糟糕。

The second error form, decision errors, represents intentional behavior that proceeds as intended, yet the plan proves inadequate or inappropriate for the situation. Often referred to as “honest mistakes,” these unsafe acts represent the actions or inactions of individuals whose “hearts are in the right place,” but they either did not have the appro priate knowledge or just simply chose poorly.

决策错误可能是所有错误形式中调查最多的,可以分为三大类:程序错误、糟糕的选择和解决问题的错误(下表)。程序性决策错误(Orasanu,1993),或Rasmussen(1982)所描述的基于规则的错误,发生在高度结构化的任务中,如果X,那么做Y。航空,特别是在军事和商业部门,其本质是高度结构化的,因此,许多飞行员的决策是程序性的。在飞行的几乎所有阶段都有非常明确的程序要执行。然而,错误可能,并且经常发生,当情况没有被识别或误诊,并且应用了错误的程序。当飞行员处于高度时间紧急的紧急情况时,如起飞时发动机故障,尤其如此。

Perhaps the most heavily investigated of all error forms, decision errors can be grouped into three general categories: procedural errors, poor choices, and problem solving errors (Table 1). Procedural decision errors (Orasanu, 1993), or rule-based mistakes, as described by Rasmussen (1982), occur duringhighly structured tasks of the sorts, if X, then do Y. Aviation, particularly within the military and commercial sectors, by its very nature is highly structured, and consequently, much of pilot decision making is procedural. There are very explicit procedures to be performed at virtually all phases of flight. Still, errors can, and often do, occur when a situation is either not recognized or misdiagnosed, and the wrong procedure is applied. This is particularly true when pilots are placed in highly time-critical emergencies like an engine malfunction on takeoff.

不过,即使在航空领域,也不是所有情况都有相应的程序来处理。因此,许多情况需要在多个响应选项中做出选择。设想一下,飞行员在离开家人一周后飞回家,意外地在他的路上遇到了一系列雷暴。他可以选择在天气周围飞行,转移到另一个领域,直到天气过去,或者穿透天气,希望快速过渡。面对这样的情况,可能会出现选择决策错误(Orasanu,1993)或基于知识的错误(Rasmussen,1986)。当缺乏足够的经验、时间或其他可能妨碍正确决策的外部压力时,这一点尤其正确。简而言之,有时我们选择得很好,有时我们没有。

However, even in aviation, not all situations have corresponding procedures to deal with them. Therefore, many situations require a choice to be made among multiple response options. Consider the pilot flying home after a long week away from the family who unexpectedly confronts a line of thunderstorms directly in his path. He can choose to fly around the weather, divert to another field until the weather passes, or penetrate the weather hoping to quickly transition through it. Confronted with situations such as this, choice decision errors (Orasanu, 1993), or knowledge-based mistakes as they are otherwise known (Rasmussen, 1986), may occur. This is particularly true when there is insufficient experience, time, or other outside pressures that may preclude correct decisions. Put simply, sometimes we chose well, and sometimes we don’t.

最后,有时对问题没有很好的理解,没有正式的程序和应对方案。正是在这些不明确的情况下,需要发明新的解决方案。从某种意义上说,个人发现自己在没有人到过的地方,在许多方面,必须按部就班。处于这种情况下的个体必须采取缓慢而努力的推理过程,而时间是一种奢侈品,很少提供。毫不奇怪,虽然这种类型的决策比其他形式的决策更少见,但犯下的解决问题错误的相对比例明显更高。

Finally, there are occasions when a problem is not well understood, and formal procedures and response options are not available. It is during these ill-defined situations that the invention of a novel solution is required. In a sense, individuals find themselves where no one has been before, and in many ways, must literally fly by the seats of their pants. Individuals placed in this situation must resort to slow and effortful reasoning processes where time is a luxury rarely afforded. Not surprisingly, while this type of decision making is more infrequent then other forms, the relative proportion of problem-solving errors committed is markedly higher.

2.2.1.3 Perceptual errors

毫不意外,当一个人对世界的感知与现实不同时,错误就可能发生,而且经常发生。通常,当感觉输入退化或“异常”时,就发生知觉错误,如视错觉和空间定向障碍,或者机组人员简单地误判飞机的高度、姿态或空速(表1)。例如,当大脑试图用它认为属于视觉贫乏环境的东西来“填补空白”时,就发生了视觉错觉,比如在夜间或在恶劣天气中飞行时看到的东西。同样地,当前系统无法分辨一个人在空间中的方位时,就会发生空间定向障碍,因此会做出“最佳猜测”-通常是在夜间或在恶劣天气下飞行时缺乏视觉(地平线)线索。在这两种情况下,不知情的个人往往会做出基于错误信息的决定,并且犯错误的可能性会提高。

Not unexpectedly, when one’s perception of the world differs from reality, errors can, and often do, occur. Typically, perceptual errors occur when sensory input is degraded or “unusual,” as is the case with visual illusions and spatial disorientation or when aircrew simply misjudge the aircraft’s altitude, attitude, or airspeed (Table 1). Visual illusions, for example, occur when the brain tries to “fill in the gaps” with what it feels belongs in a visually impoverished environment, like that seen at night or when flying in adverse weather. Likewise, spatial disorientation occurs when the vestibular system cannot resolve one’s orientation in space and therefore makes a “best guess” — typically when visual (horizon) cues are absent at night or when flying in adverse weather. In either event, the unsuspecting individual often is left to make a decision that is based on faulty information and the potential for committing an error is elevated.

然而,重要的是要注意,这不是错觉或迷失方向被归类为感知错误。相反,它是飞行员对错觉或迷失方向的错误反应。例如,许多毫无戒心的飞行员都经历过“黑洞”方法,只是为了驾驶一架完全完好的飞机进入地形或水中。这种情况继续发生,即使众所周知的是,在夜间在黑暗的、无特征的地形(例如,没有树木的湖或田野),将产生飞机实际上比它高的错觉。因此,飞行员被教导依靠他们的主要仪器,而不是外部世界,特别是在飞行的接近阶段。即便如此,一些飞行员在夜间飞行时未能监控他们的仪器。不幸的是,这些机组人员和其他被幻觉和其他迷失方向的飞行制度所愚弄的人可能最终卷入致命的飞机事故。

It is important to note, however, that it is not the illusion or disorientation that is classified as a perceptual error. Rather, it is the pilot’s erroneous response to the illusion or disorientation. For example, many unsuspecting pilots have experienced “black-hole” approaches, only to fly a perfectly good aircraft into the terrain or water. This continues to occur, even though it is well known that flying at night over dark, featureless terrain (e.g., a lake or field devoid of trees), will produce the illusion that the aircraft is actually higher than it is. As a result, pilots are taught to rely on their primary instruments, rather than the outside world, particularly during the approach phase of flight. Even so, some pilots fail to monitor their instruments when flying at night. Tragically, these aircrew and others who have been fooled by illusions and other disorientating flight regimes may end up involved in a fatal aircraft accident.

2.1.2 Violations

根据定义,错误发生在一个组织所支持的规则和条例之内;通常支配大多数事故数据库。相比之下,违规表示对管理安全飞行的规则和条例的故意无视,并且幸运地,由于它们经常涉及死亡,因此发生频率要低得多(Shappell等人,1999年b)。

By definition, errors occur within the rules and regulations espoused by an organization; typically dominating most accident databases. In contrast, violations represent a willful disregard for the rules and regulations that govern safe flight and, fortunately, occur much less frequently since they often involve fatalities (Shappell et al., 1999b).

2.1.2.1 Routine violations

虽然有许多方法来区分不同类型的违规行为,两种不同的形式已被确定,根据其病因,这将有助于安全专业人员确定事故的因果因素。第一种是日常违规行为,往往是习惯性的,往往被管理当局容忍(Rea son,1990)。例如,考虑一个人,他的驾驶速度一直比法律允许的速度快5-10英里/小时,或者一个人,当他只被授权在可视气象条件下飞行时,他经常在边缘天气飞行。虽然两者都肯定违反了管理法规,但许多其他人也在做同样的事情。此外,在55英里/小时的区域中驾驶64英里/小时的人几乎总是在55英里/小时的区域中驾驶64英里/小时。也就是说,他们“经常”违反速度限制。同样的情况也可以典型地适用于那些经常飞进恶劣天气的飞行员。

While there are many ways to distinguish between types of violations, two distinct forms have been iden tified, based on their etiology, that will help the safety professional when identifying accident causal factors. The first, routine violations, tend to be habitual by nature and often tolerated by governing authority (Rea son, 1990). Consider, for example, the individual who drives consistently 5-10 mph faster than allowed by law or someone who routinely flies in marginal weather when authorized for visual meteorological conditions only. While both are certainly against the governing regulations, many others do the same thing. Further more, individuals who drive 64 mph in a 55 mph zone, almost always drive 64 in a 55 mph zone. That is, they “routinely” violate the speed limit. The same can typically be said of the pilot who routinely flies into mar ginal weather.

更糟糕的是,这些违规行为(通常被称为“弯曲”规则)通常是被容忍的,实际上是被监管当局批准的(也就是说,你不太可能收到交通罚单,除非你超过规定的限速10英里每小时)。然而,如果地方当局开始对高速公路上超过限速9英里或更低的速度开出交通罚单(就像在军事设施上经常做的那样),那么个人违反规定的可能性就会降低。因此,从定义上讲,如果发现了日常违规行为,就必须进一步查看监管链,以确定那些没有执行规则的当权者。

What makes matters worse, these violations (com monly referred to as “bending” the rules) are often tolerated and, in effect, sanctioned by supervisory authority (i.e., you’re not likely to get a traffic citation until you exceed the posted speed limit by more than 10 mph). If, however, the local authorities started handing out traffic citations for exceeding the speed limit on the highway by 9 mph or less (as is often done on military installations), then it is less likely that individuals would violate the rules. Therefore, by definition, if a routine violation is identified, one must look further up the supervisory chain to identify those individuals in authority who are not enforcing the rules.

2.1.2.2 Exceptional violations

另一方面,与常规侵犯行为不同的是,越权侵犯行为表现为对权力的孤立背离,并不一定表明个人的类型行为模式,也不被管理层所纵容(Reason,1990)。例如,一个孤立的例子,驾驶105英里每小时在55英里每小时的区域被认为是一个例外的违规。同样地,在桥下飞行或从事其他被禁止的机动,如低空峡谷跑,将构成例外。但是,必须指出,虽然大多数例外的违反行为令人震惊,但由于其极端性质,它们并不被视为“例外”。相反,他们被认为是特殊的,因为他们既不是典型的个人,也没有得到权威的宽恕。尽管如此,对于任何组织来说,特别难以处理的违规行为的原因是,它们并不代表一个人的行为,因此,特别难以预测。事实上,当人们面对自己可怕行为的证据并要求他们做出解释时,他们往往得不到什么解释。事实上,那些从这种常规中幸存下来的人清楚地知道,如果被抓住,可怕的后果将随之而来。尽管如此,许多其他方面的模范公民还是走上了这条潜在的悲剧之路。

On the other hand, unlike routine violations, exceptional violations appear as isolated departures from authority, not necessarily indicative of individual’s typi cal behavior pattern nor condoned by management (Reason, 1990). For example, an isolated instance of driving 105 mph in a 55 mph zone is considered an exceptional violation. Likewise, flying under a bridge or engaging in other prohibited maneuvers, like low-level canyon running, would constitute an exceptional viola tion. However, it is important to note that, while most exceptional violations are appalling, they are not consid ered “exceptional” because of their extreme nature. Rather, they are considered exceptional because they are neither typical of the individual nor condoned by au thority. Still, what makes exceptional violations par ticularly difficult for any organization to deal with is that they are not indicative of an individual’s behavioral repertoire and, as such, are particularly difficult to predict. In fact, when individuals are confronted with evidence of their dreadful behavior and asked to explain it, they are often left with little explanation. Indeed, those individuals who survived such excur sions from the norm clearly knew that, if caught, dire consequences would follow. Still, defying all logic, many otherwise model citizens have been down this potentially tragic road.

| Level | Tie | Type | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unsafe acts | ERRORS | Skillbased Errors | Break down in visual scan |

| Unsafe acts | ERRORS | Skillbased Errors | Failed to prioritize attention |

| Unsafe acts | ERRORS | Skillbased Errors | Inadvertent use of flight controls |

| Unsafe acts | ERRORS | Skillbased Errors | Omitted step in procedure |

| Unsafe acts | ERRORS | Skillbased Errors | Omitted checklist item |

| Unsafe acts | ERRORS | Skillbased Errors | Poor technique |

| Unsafe acts | ERRORS | Skillbased Errors | Overcontrolled the aircraft |

| Unsafe acts | ERRORS | Decision Errors | Improper procedure |

| Unsafe acts | ERRORS | Decision Errors | Misdiagnosed emergency |

| Unsafe acts | ERRORS | Decision Errors | Wrong response to emergency |

| Unsafe acts | ERRORS | Decision Errors | Exceeded ability |

| Unsafe acts | ERRORS | Decision Errors | Inappropriate maneuver |

| Unsafe acts | ERRORS | Decision Errors | Poor decision |

| Unsafe acts | ERRORS | Perceptual Errors (due to) | Misjudged distance/altitude/airspeed |

| Unsafe acts | ERRORS | Perceptual Errors (due to) | Spatial disorientation |

| Unsafe acts | VIOLATIONS | Failed to adhere to brief | |

| Unsafe acts | VIOLATIONS | Failed to use the radar altimeter | |

| Unsafe acts | VIOLATIONS | Flew an unauthorized approach | |

| Unsafe acts | VIOLATIONS | Violated training rules | |

| Unsafe acts | VIOLATIONS | Flew an overaggressive maneuver | |

| Unsafe acts | VIOLATIONS | Failed to properly prepare for the flight | |

| Unsafe acts | VIOLATIONS | Briefed unauthorized flight | |

| Unsafe acts | VIOLATIONS | Not current/qualified for the mission | |

| Unsafe acts | VIOLATIONS | Intentionally exceeded the limits of the aircraft | |

| Unsafe acts | VIOLATIONS | Unauthorized lowaltitude canyon running | |

| Unsafe acts | VIOLATIONS | Continued lowaltitude flight in VMC |

2.2 Preconditions for Unsafe Acts

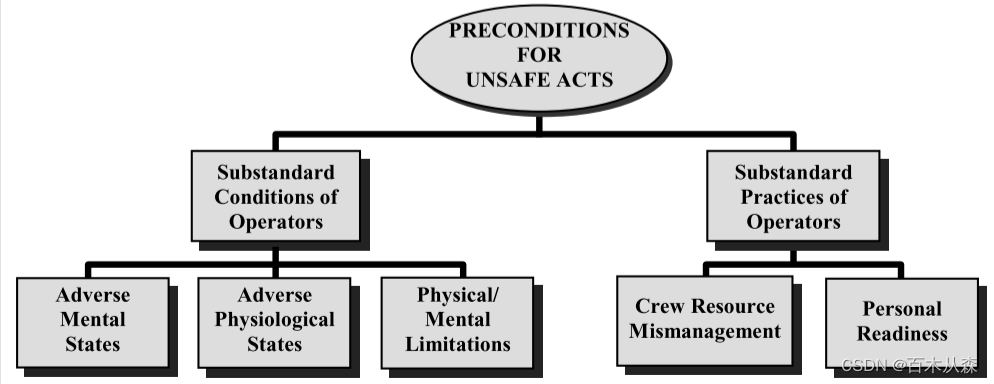

可以说,飞行员的不安全行为与近80%的航空事故直接相关。然而,仅仅关注不安全行为就像关注发烧而不了解引起发烧的潜在疾病。因此,调查人员必须更深入地挖掘不安全行为发生的原因。作为第一步,对不安全的机组人员条件进行了两个主要的细分:操作人员的不合标准的条件和他们所采取的基本标准做法(下图)。

Arguably, the unsafe acts of pilots can be directly linked to nearly 80 % of all aviation accidents. However, simply focusing on unsafe acts is like focusing on a fever without understanding the underlying disease causing it. Thus, investigators must dig deeper into why the unsafe acts took place. As a first step, two major subdi visions of unsafe aircrew conditions were developed: substandard conditions of operators and the substandard practices they commit .

2.2.1 Substandard Conditions of Operators

2.2.1.1 Adverse mental states

不良心理状态。精神上的准备在几乎所有的努力中都是至关重要的,但在飞行中可能更重要。因此,不良心理状态 这一类别被创建来解释那些影响表现的心理状态(表2)。其中主要包括情境意识的丧失、任务固定、注意力分散和由于睡眠不足或其他压力源导致的心理疲劳。这一类别还包括个性特征和有害的态度,如过度自信、自满和错误的动机。

Adverse mental states. Being prepared mentally is critical in nearly every endeavor, but perhaps even more so in aviation. As such, the category of Adverse Mental States was created to account for those mental conditions that affect performance (Table 2). Principal among these are the loss of situational awareness, task fixation, distraction, and mental fatigue due to sleep loss or other stressors. Also included in this category are personality traits and pernicious atti tudes such as overconfidence, complacency, and mis placed motivation.

可以预见的是,如果一个人由于某种原因感到精神疲劳,那么出错的可能性就会增加。同样,过分自信和其他有害的态度,如傲慢和冲动,也会影响违法行为的可能性。显然,任何人为错误的框架都必须解释事件因果链中预先存在的不利心理状态。

Predictably, if an individual is mentally tired for whatever reason, the likelihood increase that an error will occur. In a similar fashion, overconfidence and other pernicious attitudes such as arrogance and impulsivity will influence the likelihood that a violation will be committed. Clearly then, any framework of human error must account for preexisting adverse mental states in the causal chain of events.

2.2.1.2 Adverse physiological states

不良的生理状态。第二类,不利生理状态,是指那些妨碍安全操作的医学或生理状况。如前所述的视错觉、空间迷失以及身体疲劳等状况对航空特别重要。还有无数已知会影响表现的药理学和医学异常。

Adverse physiological states. The second category, adverse physiological states, refers to those medical or physiological conditions that preclude safe opera tions (Table 2). Particularly important to aviation are such conditions as visual illusions and spatial disori entation as described earlier, as well as physical fa tigue, and the myriad of pharmacological and medical abnormalities known to affect performance.

大多数飞行员都知道视觉错觉和空间定向障碍的影响。然而,飞行员们不太了解的是,经常忽视的是仅仅生病对驾驶舱内性能的影响。我们几乎所有人都曾带着病去上班,服用了非处方药,而且通常表现良好。然而,考虑到飞行员正在遭受普通的头部感冒。不幸的是,大多数飞行员认为头部感冒只是个小麻烦,使用非处方的抗组胺药、对乙酰氨基酚和其他非处方药就能轻松治愈。事实上,当面对鼻塞时,飞行员通常只关心随着机舱高度的变化而产生的鼻窦阻塞的影响。然而,这并不是当地飞行外科医生所关心的明显症状。更令人担忧的是,当进入仪器气象条件时,伴随而来的内耳感染和空间定向障碍的可能性增加,更不用说抗组胺药的副作用、疲劳和飞行员决策的睡眠不足。因此,任何安全专业人员都有责任在事件的因果链中解释这些有时微妙的医疗条件。

The effects of visual illusions and spatial disorientation are well known to most aviators. However, less well known to aviators, and often overlooked are the effects on cockpit performance of simply being ill. Nearly all of us have gone to work ill, dosed with over-the-counter medications, and have generally performed well. Consider however, the pilot suffering from the common head cold. Unfortunately, most aviators view a head cold as only a minor inconvenience that can be easily remedied using over-the counter antihistamines, acetaminophen, and other non-prescription pharmaceuticals. In fact, when confronted with a stuffy nose, aviators typically are only concerned with the effects of a painful sinus block as cabin altitude changes. Then again, it is not the overt symptoms that local flight surgeons are concerned with. Rather, it is the accompanying inner ear infection and the increased likelihood of spatial disorientation when entering instrument meteorological conditions that is alarming - not to mention the side-effects of antihistamines, fatigue, and sleep loss on pilot decision-making. Therefore, it is incumbent upon any safety professional to account for these sometimes subtle medical conditions within the causal chain of events.

2.2.1.3 Physical/Mental Limitations

身体/精神的限制。第三种也是最后一种不合标准的情况涉及个人的身体/精神限制。具体地说,这一类是指任务需要超出控制人员能力的情况。例如,人类的视觉系统在夜间受到严重限制;然而,就像开车一样,司机不一定要减速或采取额外的预防措施。在航空领域,虽然减速并不总是一种选择,但额外关注基本的飞行准则和增加飞行里程往往会增加安全边际。不幸的是,如果不采取预防措施,结果可能是灾难性的,因为飞行员经常会由于视野中物体的大小或对比度而看不到其他飞机、障碍物或电线。

Physical/Mental Limitations. The third, and final, substandard condition involves individual physical/mental limitations. Specifically, this cat egory refers to those instances when mission requirements exceed the capabilities of the individual at the controls. For example, the human visual system is severely limited at night; yet, like driving a car, drivers do not necessarily slow down or take additional precautions. In aviation, while slowing down isn’t always an option, paying additional attention to basic flight instruments and increasing one’s vigi lance will often increase the safety margin. Unfortunately, when precautions are not taken, the result can be catastrophic, as pilots will often fail to see other aircraft, obstacles, or power lines due to the size or contrast of the object in the visual field.

类似地,有时完成一项任务或行动所需的时间超出了个人的能力。每个人处理和回应信息的能力差异很大。然而,优秀的飞行员通常以其快速准确的反应能力而著称。然而,有充分的证据表明,如果要求个人迅速作出反应(即,有更少的时间来彻底考虑所有的可能性或选择),出错的可能性就会显著增加。因此,当面临快速处理和反应时间的需要时,就像大多数航空紧急情况一样,所有形式的错误都会加剧,这一点也不奇怪。

Similarly, there are occasions when the time re quired to complete a task or maneuver exceeds an individual’s capacity. Individuals vary widely in their ability to process and respond to information. Nevertheless, good pilots are typically noted for their ability to respond quickly and accurately. It is well documented, however, that if individuals are required to respond quickly (i.e., less time is available to consider all the possibilities or choices thoroughly), the probability of making an error goes up markedly. Consequently, it should be no surprise that when faced with the need for rapid processing and reaction times, as is the case in most aviation emergencies, all forms of error would be exacerbated.

除了上述基本的感官和信息处理限制,至少还有两个额外的生理/心理限制需要解决,尽管它们经常被大多数安全专业人员忽略。这些限制包括那些根本不适合飞行的人,因为他们要么身体不适合飞行,要么没有飞行的能力。例如,一些人根本没有足够的体力在潜在的高G环境下飞行,或者由于人体测量的原因,根本无法达到控制。换句话说,驾驶舱的设计传统上并没有考虑到所有的形状、大小和物理能力。同样,并不是每个人都有驾驶飞机的智力或资质。正如不是所有人都能成为音乐会钢琴家或美国橄榄球联盟的中后卫一样,并不是每个人都有驾驶飞机的天赋——这一职业需要在生命受到威胁的情况下做出快速决策和准确反应的独特能力。对于安全专业人员来说,困难的任务是确定是否资质可能导致了事故的因果顺序。

In addition to the basic sensory and information processing limitations described above, there are at least two additional instances of physical/mental limitations that need to be addressed, albeit they are often overlooked by most safety professionals. These limitations involve individuals who simply are not compatible with aviation, because they are either unsuited physically or do not possess the aptitude to fly. For example, some individuals simply don’t have the physical strength to operate in the potentially high-G environment of aviation, or for anthropometric reasons, simply have difficulty reaching the controls. In other words, cockpits have traditionally not been designed with all shapes, sizes, and physical abilities in mind. Likewise, not everyone has the mental ability or aptitude for flying aircraft. Just as not all of us can be concert pianists or NFL linebackers, not everyone has the innate ability to pilot an aircraft – a vocation that requires the unique ability to make decisions quickly and respond accurately in life threatening situations. The difficult task for the safety professional is identifying whether aptitude might have contributed to the accident causal sequence.

2.2.2 Substandard Practices of Operators

显然,许多不符合标准的操作人员的条件可以而且确实导致不安全的行为。然而,我们对自己做了很多事情,造成了这些不合标准的条件。一般来说,操作员的不标准做法可以归纳为两类:机组资源管理不善和个人准备就绪。

Clearly then, numerous substandard conditions of operators can, and do, lead to the commission of unsafe acts. Nevertheless, there are a number of things that we do to ourselves that set up these substandard conditions. Generally speaking, the substandard practices of operators can be summed up in two categories: crew resource mismanagement and personal readiness.

2.2.2.1 Crew Resource Mismanagement

机组资源管理不善。几十年来,良好的沟通技巧和团队协调一直是工业/组织和人事心理学的咒语。不足为奇的是,机组资源管理在过去几十年里一直是航空航天的基石(Helmreich & Foushee, 1993)。因此,就产生了机组资源管理不善这一类别,以解释人员之间缺乏协调的情况。在航空方面,这包括飞机内部和与空中交通管制设施和维修管制之间的协调,以及必要时与设施和其他支助人员的协调。但是空勤人员之间的协调并不仅限于飞行中的空勤人员。它还包括在飞行前后与机组人员的简要和汇报进行协调。

Crew Resource Mismanagement. Good communication skills and team coordination have been the mantra of industrial/organizational and personnel psychology for decades. Not surprising then, crew resource management has been a cornerstone of aviation for the last few decades (Helmreich & Foushee, 1993). As a result, the category of crew resource mismanagement was created to account for occurrences of poor coordination among personnel. Within the context of aviation, this includes coordination both within and between aircraft with air traffic control facilities and maintenance control, as well as with facility and other support personnel as necessary. But aircrew coordination does not stop with the aircrew in flight. It also includes coordination before and after the flight with the brief and debrief of the aircrew.

不难想象,由于机组人员缺乏协调,导致驾驶舱内的混乱和决策失误,从而导致事故发生的情景。事实上,航空事故数据库中充斥着机组人员之间缺乏协调的例子。更悲惨的例子之一是1972年一架民用飞机在佛罗里达沼泽地的夜晚坠毁,当时机组人员正忙着排除信号灯烧坏的原因。不幸的是,驾驶舱里没有人在监控飞机的高度,因为高度保持不小心断开了。理想情况下,机组人员应该协调解决问题的工作,确保至少有一名机组人员在监控基本的飞行准则和“驾驶”飞机。然而,事实并非如此,因为他们进入了一个缓慢的、不为人所知的沼泽地,导致了大量的死亡。

It is not difficult to envision a scenario where the lack of crew coordination has led to confusion and poor decision making in the cockpit, resulting in an accident. In fact, aviation accident databases are replete with instances of poor coordination among aircrew. One of the more tragic examples was the crash of a civilian airliner at night in the Florida Everglades in 1972 as the crew was busily trying to troubleshoot what amounted to a burnt out indicator light. Unfortunately, no one in the cockpit was monitoring the aircraft’s altitude as the altitude hold was inadvertently disconnected. Ideally, the crew would have coordinated the trouble-shooting task ensuring that at least one crewmember was monitoring basic flight instruments and “flying” the aircraft. Tragically, this was not the case, as they entered a slow, unrecognized, descent into the everglades resulting in numerous fatalities.

2.2.2.2 Personal Readiness

个人准备。在航空行业,或者在任何职业环境中,员工都应该准备好以最佳水平工作。然而,在航空行业,就像在其他行业一样,当个人在身体或精神上没有做好执勤准备时,就会出现个人准备不足的情况。例如,违反乘务人员休息要求、从bottle-to-brief rules和自我治疗都会影响工作表现,在飞机上尤其有害。不难想象,当个体违反机组休息要求时,就会面临精神疲劳等不良心理状态的风险,最终导致错误和事故的发生。然而,需要注意的是,影响个人准备状态的违例行为并不被认为是“不安全行为,违例行为”,因为它们通常不会发生在驾驶舱内,也不一定是具有直接和直接后果的主动故障。

Personal Readiness. In aviation, or for that matter in any occupational setting, individuals are expected to show up for work ready to perform at optimal levels. Nevertheless, in aviation as in other profes sions, personal readiness failures occur when individuals fail to prepare physically or mentally for duty. For instance, violations of crew rest requirements, bottle-to-brief rules, and self-medicating all will af fect performance on the job and are particularly detrimental in the aircraft. It is not hard to imagine that, when individuals violate crew rest requirements, they run the risk of mental fatigue and other adverse mental states, which ultimately lead to errors and accidents. Note however, that violations that affect personal readiness are not considered “unsafe act, violation” since they typically do not happen in the cockpit, nor are they necessarily active failures with direct and immediate consequences.

然而,并不是所有的个人准备失败都是由于违反管理规则或条例造成的。例如,在驾驶一架飞机之前跑10英里可能并不违反任何现有的规定,但它可能损害个人的身体和精神能力,足以降低表现,并引发不安全行为。同样,现代商人传统的“糖果和可乐”午餐可能听起来不错,但可能不足以在严格的环境中维持业绩。虽然可能没有规定这种行为,但飞行员在决定自己是否“适合”驾驶飞机时,必须有良好的判断力。

Still, not all personal readiness failures occur as a result of violations of governing rules or regulations. For example, running 10 miles before piloting an aircraft may not be against any existing regulations, yet it may impair the physical and mental capabilities of the individual enough to degrade performance and elicit unsafe acts. Likewise, the traditional “candy bar and coke” lunch of the modern businessman may sound good but may not be sufficient to sustain performance in the rigorous environment of aviation. While there may be no rules governing such behavior, pilots must use good judgment when deciding whether they are “fit” to fly an aircraft.

| Level | Tie | Type | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Conditions of Operators | Adverse mental states | Channelized attention |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Conditions of Operators | Adverse mental states | Complacency |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Conditions of Operators | Adverse mental states | Distraction |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Conditions of Operators | Adverse mental states | Mental fatigue |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Conditions of Operators | Adverse mental states | Get-home-itis |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Conditions of Operators | Adverse mental states | Haste |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Conditions of Operators | Adverse mental states | Loss of situational awareness |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Conditions of Operators | Adverse mental states | Misplaced motivation |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Conditions of Operators | Adverse mental states | Task saturation |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Conditions of Operators | Adverse physiological states | Impaired physiological state |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Conditions of Operators | Adverse physiological states | Medical illness |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Conditions of Operators | Adverse physiological states | Physiological incapacitation |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Conditions of Operators | Adverse physiological states | Physical fatigue |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Conditions of Operators | Physical/Mental Limitations | Insufficient reaction time |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Conditions of Operators | Physical/Mental Limitations | Visual limitation |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Conditions of Operators | Physical/Mental Limitations | Incompatible intelligence/aptitude |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Conditions of Operators | Physical/Mental Limitations | Incompatible physical capability |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Practices of Operators | Crew Resource Mismanagement | Failed to back-up |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Practices of Operators | Crew Resource Mismanagement | Failed to communicate/coordinate |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Practices of Operators | Crew Resource Mismanagement | Failed to conduct adequate brief |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Practices of Operators | Crew Resource Mismanagement | Failed to use all available resources |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Practices of Operators | Crew Resource Mismanagement | Failure of leadership |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Practices of Operators | Crew Resource Mismanagement | Misinterpretation of traffic calls |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Practices of Operators | Personal Readiness | Excessive physical training |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Practices of Operators | Personal Readiness | Self-medicating |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Practices of Operators | Personal Readiness | Violation of crew rest requirement |

| Preconditions for Unsafe Acts | Substandard Practices of Operators | Personal Readiness | Violation of bottle-to-throttle requirement |

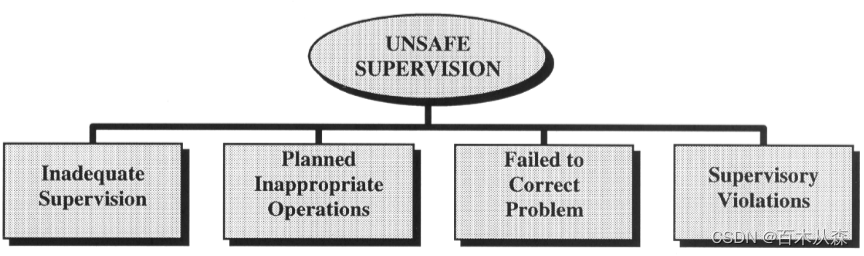

2.3 Unsafe Supervision

回想一下,除了与飞行员/操作员相关的那些因果因素外,Reason》(1990)追溯了因果事件链,追溯了超指挥链。因此,我们已经确定了四类不安全的监管:监管不足,计划不当的操作,未能纠正已知问题,以及监管违规(图4)。每一类都在下面简要描述。

2.3.1 Inadequate Supervision

监督不足。任何主管的角色都是提供成功的机会。要做到这一点,主管,无论在什么级别的操作,必须提供指导,培训机会,领导和动机,以及适当的角色模型,以供模仿。不幸的是,情况并非总是如此。例如,不难想象这样一种情况,即没有为某一特定的机组人员提供充分的机组人员资源管理培训,或者没有为某一特定的机组人员提供参加这种培训的机会。可以想象,机组人员的协调能力将受到损害,如果飞机被置于不利的情况(例如紧急情况),出错的风险将会加剧,发生事故的可能性将显著增加。

Inadequate Supervision. The role of any supervisor is to provide the opportunity to succeed. To do this, the supervisor, no matter at what level of operation, must provide guidance, training opportunities, lead ership, and motivation, as well as the proper role model to be emulated. Unfortunately, this is not always the case. For example, it is not difficult to conceive of a situation where adequate crew resource management training was either not provided, or the opportunity to attend such training was not afforded to a particular aircrew member. Conceivably, aircrew coordination skills would be compromised and if the aircraft were put into an adverse situation (an emer gency for instance), the risk of an error being com mitted would be exacerbated and the potential for an accident would increase markedly.

同样,良好的专业指导和监督是任何成功组织的基本要素。虽然赋予个人独立决策和运作的权力当然是必要的,但这并不会使监督者脱离责任。缺乏指导和监督已被证明是滋生许多违规行为的温床,这些违规行为已经蔓延到驾驶舱内。因此,任何对事故原因的彻底调查都必须考虑到监管在人为错误发生过程中所扮演的角色(即监管是否不当或根本没有发生)

In a similar vein, sound professional guidance and oversight is an essential ingredient of any successful organization. While empowering individuals to make decisions and function independently is certainly essential, this does not divorce the supervisor from accountability. The lack of guidance and oversight has proven to be the breeding ground for many of the violations that have crept into the cockpit. As such, any thorough investigation of accident causal factors must consider the role supervision plays (i.e., whether the supervision was inappropriate or did not occur at all) in the genesis of human error

2.3.2 Planned Inappropriate Operations

计划外的不当操作。有时,操作节奏和/或空乘人员的调度是这样的,个人被置于不可接受的风险,机组人员休息受到危害,并最终性能受到不利影响。在紧急情况下,这样的行动虽然是不可避免的,但在正常的行动中是不可接受的。因此,第二类不安全的监督,计划不当的操作,被创建来解释这些失败

Planned Inappropriate Operations. Occasionally, the operational tempo and/or the scheduling of air crew is such that individuals are put at unacceptable risk, crew rest is jeopardized, and ultimately perfor mance is adversely affected. Such operations, though arguably unavoidable during emergencies, are unac ceptable during normal operations. Therefore, the second category of unsafe supervision, planned inap propriate operations, was created to account for these failures

以机组配对不当的问题为例。众所周知,当非常高级、专横的机长与非常低级、能力较弱的副机长搭档时,很可能会出现沟通和协调问题。通常被称为跨座舱权威梯度,这样的条件可能导致了1982年1月一架商业客机在华盛顿特区外的波托马克河的悲剧坠毁(NTSB, 1982)。在那次事故中,当副机长指出发动机准则似乎不正常时,机长多次对副机长进行了重击。机长毫不气馁,在结冰的条件下,以不足的起飞推力继续了一次致命的起飞。飞机失速,坠入结冰的河中,机组人员和许多乘客遇难。

Take, for example, the issue of improper crew pairing. It is well known that when very senior, dictatorial captains are paired with very junior, weak co-pilots, communication and coordination prob lems are likely to occur. Commonly referred to as the trans-cockpit authority gradient, such conditions likely contributed to the tragic crash of a commercial airliner into the Potomac River outside of Washing ton, DC, in January of 1982 (NTSB, 1982). In that accident, the captain of the aircraft repeatedly re buffed the first officer when the latter indicated that the engine instruments did not appear normal. Un daunted, the captain continued a fatal takeoff in icing conditions with less than adequate takeoff thrust. The aircraft stalled and plummeted into the icy river, killing the crew and many of the passengers.

很明显,机长长和机组成员都有责任。他们死于事故,无法阐明原因;但是,这个监督链的作用是什么呢?也许机组成员配对同样负有责任。虽然在报告中没有具体论述,但在许多事故中,这些问题显然是值得探讨的。事实上,在那次事故中,还发现了其他几个培训和人员配备问题。

Clearly, the captain and crew were held account able. They died in the accident and cannot shed light on causation; but, what was the role of the supervi sory chain? Perhaps crew pairing was equally respon sible. Although not specifically addressed in the report, such issues are clearly worth exploring in many acci dents. In fact, in that particular accident, several other training and manning issues were identified.

2.3.3 Failure to Correct a Known Problem

未能纠正已知问题。已知不安全监管的第三类,未纠正已知问题,指的是那些个人、设备、培训或其他相关安全领域存在缺陷的情况,这些缺陷被主管“知道”,但被允许继续存在。例如,事故调查人员在一次致命的坠机事故后采访飞行员的朋友、同事和主管,结果却发现他们“知道这事总有一天会发生在他身上”,这种情况并不少见。如果主管知道一名飞行员没有能力安全飞行,但还是允许他飞行,他显然没有给飞行员任何好处。无论是通过补救性培训,还是在必要时取消飞行资格,都未能纠正这种行为,这意味着该飞行员已被判处死刑,更不用说机上其他乘客了。

Failure to Correct a Known Problem. The third category of known unsafe supervision, Failed to Cor rect a Known Problem, refers to those instances when deficiencies among individuals, equipment, training or other related safety areas are “known” to the supervisor, yet are allowed to continue unabated (Table 3). For example, it is not uncommon for accident investigators to interview the pilot’s friends, colleagues, and supervisors after a fatal crash only to find out that they “knew it would happen to him some day.” If the supervisor knew that a pilot was incapable of flying safely, and allowed the flight anyway, he clearly did the pilot no favors. The failure to correct the behavior, either through remedial train ing or, if necessary, removal from flight status, essen tially signed the pilot’s death warrant - not to mention that of others who may have been on board.

同样地,如果不能始终如一地纠正或约束不适当的行为,肯定会滋生不安全的气氛,促进违反规则的行为。亚维亚航空的历史是丰富的,有飞行员的报告,他们讲述了令人毛骨悚然的故事,他们的功绩和巡回低空飞行(臭名昭著的“到过那里,做过那件事”)。虽然对一些人来说很有趣,但它们经常用来宣传一种宽容和“高人一等”的观念,直到有一天有人打破了地面低空飞行的记录!事实上,未能报告这些不安全倾向并采取纠正行动,是未能纠正已知问题的又一个例子。

Likewise, the failure to consistently correct or disci pline inappropriate behavior certainly fosters an unsafe atmosphere and promotes the violation of rules. Avia tion history is rich with by reports of aviators who tell hair-raising stories of their exploits and barnstorming low-level flights (the infamous “been there, done that”). While entertaining to some, they often serve to promul gate a perception of tolerance and “one-up-manship” until one day someone ties the low altitude flight record of ground-level! Indeed, the failure to report these unsafe tendencies and initiate corrective actions is yet another example of the failure to correct known problems.

2.3.4 Supervisory Violations

违反监管规定。另一方面,违反监管行为只适用于那些被监管者故意无视的现有规则和规章的情况。尽管可以说是罕见的情况,但监管者在管理资产时偶尔会违反规则和原则。例如,在某些情况下,个人可以在没有现有资格或执照的情况下驾驶飞机。同样,也可以认为,未能执行现有的规章制度或炫耀权威也是监管层面的违法行为。尽管这种做法很少见,而且可能很难被剔除,但它公然违反了规则,并为可以预见的随之而来的悲惨事件奠定了基础。

Supervisory Violations. Supervisory violations, on the other hand, are reserved for those instances when exist ing rules and regulations are willfully disregarded by supervisors (Table 3). Although arguably rare, supervi sors have been known occasionally to violate the rules and doctrine when managing their assets. For instance, there have been occasions when individuals were permitted to operate an aircraft without current quali fications or license. Likewise, it can be argued that failing to enforce existing rules and regulations or flaunt ing authority are also violations at the supervisory level. While rare and possibly difficult to cull out, such practices are a flagrant violation of the rules and invari ably set the stage for the tragic sequence of events that predictably follow.

| Level | Tie | Type | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unsafe Supervision | Inadequate Supervision | Failed to provide guidance | |

| Unsafe Supervision | Inadequate Supervision | Failed to provide operational doctrine | |

| Unsafe Supervision | Inadequate Supervision | Failed to provide oversight | |

| Unsafe Supervision | Inadequate Supervision | Failed to provide training | |

| Unsafe Supervision | Inadequate Supervision | Failed to track qualifications | |

| Unsafe Supervision | Inadequate Supervision | Failed to track performance | |

| Unsafe Supervision | Planned Inappropriate Operations | Failed to provide correct data | |

| Unsafe Supervision | Planned Inappropriate Operations | Failed to provide adequate brief time | |

| Unsafe Supervision | Planned Inappropriate Operations | Improper manning | |

| Unsafe Supervision | Planned Inappropriate Operations | Mission not in accordance with rules/regulations | |

| Unsafe Supervision | Planned Inappropriate Operations | Provided inadequate opportunity for crew rest | |

| Unsafe Supervision | Failed to Correct a Known Problem | Failed to correct document in error | |

| Unsafe Supervision | Failed to Correct a Known Problem | Failed to identify an at-risk aviator | |

| Unsafe Supervision | Failed to Correct a Known Problem | Failed to initiate corrective action | |

| Unsafe Supervision | Failed to Correct a Known Problem | Failed to report unsafe tendencies | |

| Unsafe Supervision | Supervisory Violations | Authorized unnecessary hazard | |

| Unsafe Supervision | Supervisory Violations | Failed to enforce rules and regulations | |

| Unsafe Supervision | Supervisory Violations | Authorized unqualified crew for flight |

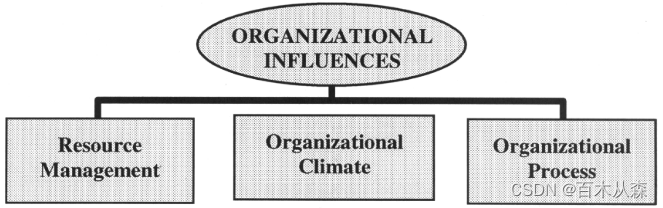

2.4 Organizational Influences

如前所述,上层管理人员的错误决定直接影响监督实践,以及操作人员的条件和行动。不幸的是,这些组织错误经常被安全专业人员忽视,这在很大程度上是由于缺乏一个明确的框架来研究它们。一般来说,最难以捉摸的潜在失败围绕着与资源管理、组织氛围和操作过程相关的问题,如下图所示。

As noted previously, fallible decisions of upper-level management directly affect supervisory practices, as well as the conditions and actions of operators. Unfor tunately, these organizational errors often go unnoticed by safety professionals, due in large part to the lack of a clear framework from which to investigate them. Gen erally speaking, the most elusive of latent failures revolve around issues related to resource management, organi zational climate, and operational processes, as detailed below in Figure 5.

2.4.1 Resource Management

资源管理。这一类包含了关于组织资产(如人力资源(人员)、货币资产和设备/设施)的配置和维护的公司级决策领域。一般来说,关于如何管理这些资源的企业决策围绕着两个截然不同的目标——安全目标和准时高效运营目标。在繁荣时期,这两个目标很容易得到平衡和充分满足。然而,正如我们前面提到的,也可能会有财政紧缩的时候,这两者之间需要一些妥协。不幸的是,历史告诉我们,在这样的战斗中,安全往往是输家,一些人可以很好地证明,在有财政困难的组织中,安全和培训往往是第一个被削减的。如果在这些领域的削减太过严重,飞行熟练程度可能会受到影响,最好的飞行员也可能离开组织去寻找更好的工作。

Resource Management. This category encompasses the realm of corporate-level decision making regard ing the allocation and maintenance of organizational assets such as human resources (personnel), monetary assets, and equipment/facilities (Table 4). Generally, corporate decisions about how such resources should be managed center around two distinct objectives – the goal of safety and the goal of on-time, costeffective operations. In times of prosperity, both objectives can be easily balanced and satisfied in full. However, as we mentioned earlier, there may also be times of fiscal austerity that demand some give and take between the two. Unfortunately, history tells us that safety is often the loser in such battles and, as some can attest to very well, safety and training are often the first to be cut in organizations having financial difficulties. If cutbacks in such areas are too severe, flight proficiency may suffer, and the best pilots may leave the organization for greener pastures.

过度削减成本还可能导致新设备的资金减少,或可能导致购买的设备不是最优的,设计不适当,以满足公司飞行的业务类型。其他涓滴效应包括设备和工作区维护不善,以及无法纠正现有设备的已知设计缺陷。其结果是,在最不理想的条件和时间安排下,飞行员驾驶的是一种非海上航行的、技术水平较低的老式和维护不良的飞机。这对航空安全的影响并不难想象。

Excessive cost-cutting could also result in reduced funding for new equipment or may lead to the pur chase of equipment that is sub optimal and inad equately designed for the type of operations flown by the company. Other trickle-down effects include poorly maintained equipment and workspaces, and the failure to correct known design flaws in existing equipment. The result is a scenario involving unsea soned, less-skilled pilots flying old and poorly main tained aircraft under the least desirable conditions and schedules. The ramifications for aviation safety are not hard to imagine.

2.4.2 Climate

气候。组织气候是指影响员工绩效的一大类组织变量。在形式上,它被定义为“组织对待个人时基于情境的一致性”(Jones, 1988)。然而,一般来说,组织气氛可以被视为组织内部的工作气氛。一个组织氛围的一个标志就是它的结构,这反映在指挥链、授权和责任、沟通渠道和正式的行动问责制(表4)。就像在驾驶舱一样,沟通和协调在一个组织中是至关重要的。如果组织内部的管理层和员工没有沟通,或者没有人知道谁在负责,那么组织的安全显然会受到影响,事故也会发生(Muchinsky, 1997)。

Climate. Organizational Climate refers to a broad class of organizational variables that influence worker performance. Formally, it was defined as the “situationally based consistencies in the organization’s treatment of individuals” (Jones, 1988). In general, however, organizational climate can be viewed as the working atmosphere within the organization. One telltale sign of an organization’s climate is its structure, as reflected in the chain-of-command, delegation of authority and responsibility, communication chan nels, and formal accountability for actions (Table 4). Just like in the cockpit, communication and coordi nation are vital within an organization. If manage ment and staff within an organization are not communicating, or if no one knows who is in charge, organizational safety clearly suffers and accidents do happen (Muchinsky, 1997).

一个组织的政策和文化也是其气候的良好指标。政策是官方的指导方针,指导管理层在招聘和解雇、晋升、留任、加薪、病假、吸毒和酗酒、加班、事故调查和安全设备的使用等方面做出决定。另一方面,文化是指一个组织中非官方的或不成文的规则、价值观、态度、生活和习俗。文化是“在这里做事的真正方式”。当政策定义不清、敌对或冲突时,或者当它们被非正式的规则和价值观所取代时,组织内部就会充满混乱。事实上,有一些公司经理在公共论坛上很快就会对官方的安全政策“口惠而实不至”,但在幕后操作时却忽视了这些政策。然而,热力学第三定律告诉我们,“秩序和和谐不能由这样的混乱和不和谐产生”。在这种情况下,安全必然受到影响。

An organization’s policies and culture are also good indicators of its climate. Policies are official guidelines that direct management’s decisions about such things as hiring and firing, promotion, reten tion, raises, sick leave, drugs and alcohol, overtime, accident investigations, and the use of safety equip ment. Culture, on the other hand, refers to the unofficial or unspoken rules, values, attitudes, be liefs, and customs of an organization. Culture is “the way things really get done around here.” When policies are ill-defined, adversarial, or con flicting, or when they are supplanted by unofficial rules and values, confusion abounds within the orga nization. Indeed, there are some corporate managers who are quick to give “lip service” to official safety policies while in a public forum, but then overlook such policies when operating behind the scenes. However, the Third Law of Thermodynamics tells us that, “order and harmony cannot be produced by such chaos and disharmony”. Safety is bound to suffer under such conditions.

2.4.3 Operational Process

操作过程。这一类是指管理组织内部日常活动的公司决策和规则,包括建立和使用标准化的操作程序,以及维护员工和管理层之间的制衡(监督)的非正常方法。例如,诸如操作节奏、时间压力、激励系统和工作时间表等因素都是会对安全产生不利影响的因素(表4)。如前所述,可能会有这样的情况,当一个组织的上层决定有必要增加操作的速度,以超出主管的人员配备能力。因此,主管可能会诉诸于使用不适当的调度程序,这将危及机组人员的休息,并产生次优的机组人员配对,使机组人员面临更大的事故风险。然而,组织应该有适当的官方程序来处理这些意外事件,以及监督计划来监测这些风险。

Operational Process. This category refers to corporate decisions and rules that govern the everyday activities within an organization, including the establishment and use of standardized operating procedures and for mal methods for maintaining checks and balances (over sight) between the workforce and management. For example, such factors as operational tempo, time pres sures, incentive systems, and work schedules are all factors that can adversely affect safety (Table 4). As stated earlier, there may be instances when those within the upper echelon of an organization determine that it is necessary to increase the operational tempo to a point that overextends a supervisor’s staffing capabilities. Therefore, a supervisor may resort to the use of inad equate scheduling procedures that jeopardize crew rest and produce sub optimal crew pairings, putting aircrew at an increased risk of a mishap. However, organiza tions should have official procedures in place to address such contingencies as well as oversight pro grams to monitor such risks.

遗憾的是,并不是所有的组织都有这些程序,他们也没有参与到通过匿名报告系统和安全审计来监测机组人员错误和人为因素问题的积极过程中。因此,主管和经理往往在事故发生前就没有意识到问题。事实上,有人说“事故是许多人的一个事件”(Reinhart, 1996)。任何组织都有责任在“奶酪上的洞”创造灾难来袭的机会之窗之前,积极地寻找并堵住它们。

Regrettably, not all organizations have these pro cedures nor do they engage in an active process of monitoring aircrew errors and human factor prob lems via anonymous reporting systems and safety audits. As such, supervisors and managers are often unaware of the problems before an accident occurs. Indeed, it has been said that “an accident is one incident to many” (Reinhart, 1996). It is incumbent upon any organization to fervently seek out the “holes in the cheese” and plug them up, before they create a window of opportunity for catastrophe to strike.

| Level | Tie | Type | Content |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organizational Influences | Resource/Acquisition Management | Human Resources | Selection |

| Organizational Influences | Resource/Acquisition Management | Human Resources | Staffing/manning |

| Organizational Influences | Resource/Acquisition Management | Human Resources | Training |

| Organizational Influences | Resource/Acquisition Management | Monetary/budget resources | Excessive cost cutting |

| Organizational Influences | Resource/Acquisition Management | Monetary/budget resources | Lack of funding |

| Organizational Influences | Resource/Acquisition Management | Equipment/facility resources | Poor design |

| Organizational Influences | Resource/Acquisition Management | Equipment/facility resources | Purchasing of unsuitable equipment |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Climate | Structure | Chain-of-command |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Climate | Structure | Delegation of authority |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Climate | Structure | Communication |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Climate | Structure | Formal accountability for actions |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Climate | Policies | Hiring and firing |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Climate | Policies | Promotion |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Climate | Policies | Drugs and alcohol |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Climate | Culture | Norms and rules |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Climate | Culture | Values and beliefs |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Climate | Culture | Organizational justice |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Process | Operations | Operational tempo |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Process | Operations | Time pressure |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Process | Operations | Production quotas |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Process | Operations | Incentives |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Process | Operations | Measurement/appraisal |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Process | Operations | Schedules |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Process | Operations | Deficient planning |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Process | Procedures | Standards |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Process | Procedures | Clearly defined objectives |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Process | Procedures | Documentation |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Process | Procedures | Instructions |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Process | Oversight | Risk management |

| Organizational Influences | Organizational Process | Oversight | Safety programs |

3 架构思维导图

3689

3689

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?