本文转载自:http://www.ruanyifeng.com/blog/2012/09/imaginary_number.html

https://betterexplained.com/articles/a-visual-intuitive-guide-to-imaginary-numbers/

另外,可在网上搜索视频《维度:数学漫步》

本文正文如下:

有人在Stack Exchange问了一个问题:

"我一直觉得虚数(imaginary number)很难懂。

中学老师说,虚数就是-1的平方根。

可是,什么数的平方等于-1呢?计算器直接显示出错!

直到今天,我也没有搞懂。谁能解释,虚数到底是什么?

它有什么用?"

帖子的下面,很多人给出了自己的解释,还推荐了一篇非常棒的文章《虚数的图解》(见后文)。我读后恍然大悟,醍醐灌顶,原来虚数这么简单,一点也不奇怪和难懂!

下面,我就用自己的语言,讲述我所理解的虚数。

一、什么是虚数?

首先,假设有一根数轴,上面有两个反向的点:+1和-1。

这根数轴的正向部分,可以绕原点旋转。显然,逆时针旋转180度,+1就会变成-1。

这相当于两次逆时针旋转90度。

因此,我们可以得到下面的关系式:

(+1) * (逆时针旋转90度) * (逆时针旋转90度) = (-1)

如果把+1消去,这个式子就变为:

(逆时针旋转90度)^2 = (-1)

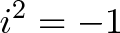

将"逆时针旋转90度"记为 i :

i^2 = (-1)

这个式子很眼熟,它就是虚数的定义公式。

所以,我们可以知道,虚数 i 就是逆时针旋转90度,i 不是一个数,而是一个旋转量。

二、复数的定义

既然 i 表示旋转量,我们就可以用 i ,表示任何实数的旋转状态。

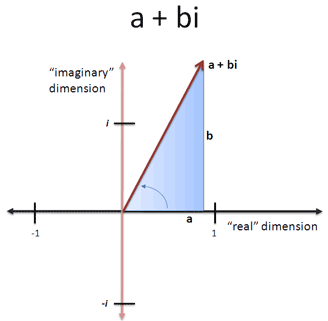

将实数轴看作横轴,虚数轴看作纵轴,就构成了一个二维平面。旋转到某一个角度的任何正实数,必然唯一对应这个平面中的某个点。

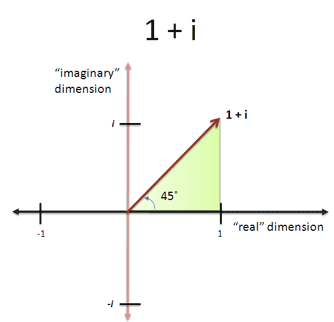

只要确定横坐标和纵坐标,比如( 1 , i ),就可以确定某个实数的旋转量(45度)。

数学家用一种特殊的表示方法,表示这个二维坐标:用 + 号把横坐标和纵坐标连接起来。比如,把 ( 1 , i ) 表示成 1 + i 。这种表示方法就叫做复数(complex number),其中 1 称为实数部,i 称为虚数部。

为什么要把二维坐标表示成这样呢,下一节告诉你原因。

三、虚数的作用:加法

虚数的引入,大大方便了涉及到旋转的计算。

比如,物理学需要计算"力的合成"。假定一个力是 3 + i ,另一个力是 1 + 3i ,请问它们的合成力是多少?

根据"平行四边形法则",你马上得到,合成力就是 ( 3 + i ) + ( 1 + 3i ) = ( 4 + 4i )。

这就是虚数加法的物理意义。

四、虚数的作用:乘法

如果涉及到旋转角度的改变,处理起来更方便。

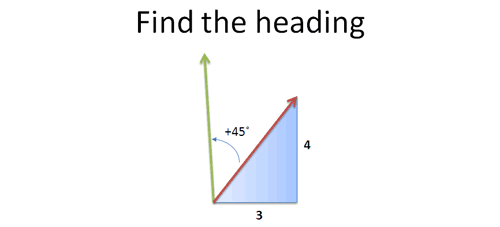

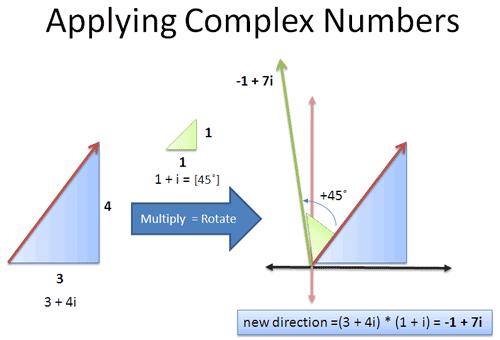

比如,一条船的航向是 3 + 4i 。

如果该船的航向,逆时针增加45度,请问新航向是多少?

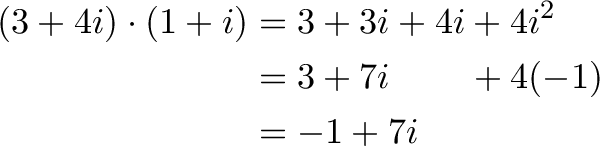

45度的航向就是 1 + i 。计算新航向,只要把这两个航向 3 + 4i 与 1 + i 相乘就可以了(原因在下一节解释):

( 3 + 4i ) * ( 1 + i ) = ( -1 + 7i )

所以,该船的新航向是 -1 + 7i 。

如果航向逆时针增加90度,就更简单了。因为90度的航向就是 i ,所以新航向等于:

( 3 + 4i ) * i = ( -4 + 3i )

这就是虚数乘法的物理意义:改变旋转角度。

五、虚数乘法的数学证明

为什么一个复数改变旋转角度,只要做乘法就可以了?

下面就是它的数学证明,实际上很简单。

任何复数 a + bi,都可以改写成旋转半径 r 与横轴夹角 θ 的形式。

假定现有两个复数 a + bi 和 c + di,可以将它们改写如下:

a + bi = r1 * ( cosα + isinα )

c + di = r2 * ( cosβ + isinβ )

这两个复数相乘,( a + bi )( c + di ) 就相当于

r1 * r2 * ( cosα + isinα ) * ( cosβ + isinβ )

展开后面的乘式,得到

cosα * cosβ - sinα * sinβ + i( cosα * sinβ + sinα * cosβ )

根据三角函数公式,上面的式子就等于

cos(α+β) + isin(α+β)

所以,

这就证明了两个复数相乘,就等于旋转半径相乘,旋转角度相加。( a + bi )( c + di ) = r1 * r2 * ( cos(α+β) + isin(α+β) )

下文为《虚数的图解》原文:

Imaginary numbers always confused me. Like understanding e, most explanations fell into one of two categories:

- It’s a mathematical abstraction, and the equations work out. Deal with it.

- It’s used in advanced physics, trust us. Just wait until college.

Gee, what a great way to encourage math in kids! Today we’ll assault this topic with our favorite tools:

- Focusing on relationships, not mechanical formulas.

- Seeing complex numbers as an upgrade to our number system, just like zero, decimals and negatives were.

- Using visual diagrams, not just text, to understand the idea.

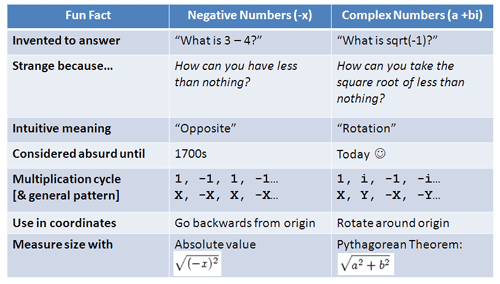

And our secret weapon: learning by analogy. We’ll approach imaginary numbers by observing its ancestor, the negatives. Here’s your guidebook:

It doesn’t make sense yet, but hang in there. By the end we’ll hunt down i and put it in a headlock, instead of the reverse.

Really Understanding Negative Numbers

Negative numbers aren’t easy. Imagine you’re a European mathematician in the 1700s. You have 3 and 4, and know you can write 4 – 3 = 1. Simple.But what about 3-4? What, exactly, does that mean? How can you take 4 cows from 3? How could you have less than nothing?

Negatives were considered absurd, something that “darkened the very whole doctrines of the equations” (Francis Maseres, 1759). Yet today, it’d be absurd to think negatives aren’t logical or useful. Try asking your teacher whether negatives corrupt the very foundations of math.

What happened? We invented a theoretical number that had useful properties. Negatives aren’t something we can touch or hold, but they describe certain relationships well (like debt). It was a useful fiction.

Rather than saying “I owe you 30” and reading words to see if I’m up or down, I can write “-30” and know it means I’m in the hole. If I earn money and pay my debts (-30 + 100 = 70), I can record the transaction easily. I have +70 afterwards, which means I’m in the clear.

The positive and negative signs automatically keep track of the direction — you don’t need a sentence to describe the impact of each transaction. Math became easier, more elegant. It didn’t matter if negatives were “tangible” — they had useful properties, and we used them until they became everyday items. Today you’d call someone obscene names if they didn’t “get” negatives.

But let’s not be smug about the struggle: negative numbers were a huge mental shift. Even Euler, the genius who discovered e and much more, didn’t understand negatives as we do today. They were considered “meaningless” results (he later made up for this in style).

It’s a testament to our mental potential that today’s children are expected to understand ideas that once confounded ancient mathematicians.

Enter Imaginary Numbers

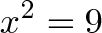

Imaginary numbers have a similar story. We can solve equations like this all day long:

The answers are 3 and -3. But suppose some wiseguy puts in a teensy, tiny minus sign:

Uh oh. This question makes most people cringe the first time they see it. You want the square root of a number less than zero? That’s absurd! (Historically, there were real questions to answer, but I like to imagine a wiseguy.)

It seems crazy, just like negatives, zero, and irrationals (non-repeating numbers) must have seemed crazy at first. There’s no “real” meaning to this question, right?

Wrong. So-called “imaginary numbers” are as normal as every other number (or just as fake): they’re a tool to describe the world. In the same spirit of assuming -1, .3, and 0 “exist”, let’s assume some number i exists where:

That is, you multiply i by itself to get -1. What happens now?

Well, first we get a headache. But playing the “Let’s pretend i exists” game actually makes math easier and more elegant. New relationships emerge that we can describe with ease.

You may not believe in i, just like those fuddy old mathematicians didn’t believe in -1. New, brain-twisting concepts are hard and they don’t make sense immediately, even for Euler. But as the negatives showed us, strange concepts can still be useful.

I dislike the term “imaginary number” — it was considered an insult, a slur, designed to hurt i‘s feelings. The number i is just as normal as other numbers, but the name “imaginary” stuck so we’ll use it.

Visual Understanding of Negative and Complex Numbers

As we saw last time, the equation x^2 = 9 really means:

or

![]()

What transformation x, when applied twice, turns 1 to 9?

The two answers are “x = 3” and “x = -3”: That is, you can “scale by” 3 or “scale by 3 and flip” (flipping or taking the opposite is one interpretation of multiplying by a negative).

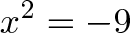

Now let’s think about x^2 = -1, which is really

![]()

What transformation x, when applied twice, turns 1 into -1? Hrm.

- We can’t multiply by a positive twice, because the result stays positive

- We can’t multiply by a negative twice, because the result will flip back to positive on the second multiplication

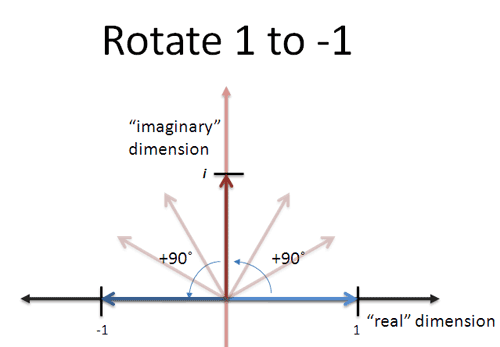

But what about… a rotation! It sounds crazy, but if we imagine x being a “rotation of 90 degrees”, then applying x twice will be a 180 degree rotation, or a flip from 1 to -1!

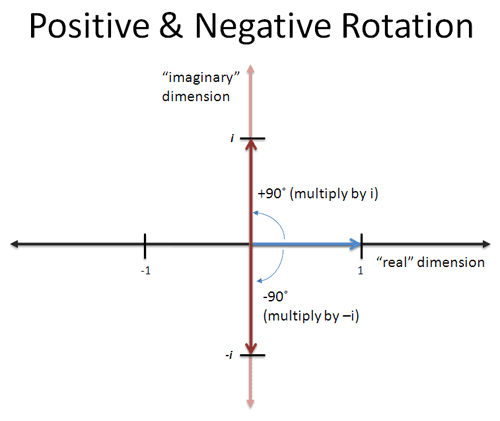

Yowza! And if we think about it more, we could rotate twice in the other direction (clockwise) to turn 1 into -1. This is “negative” rotation or a multiplication by -i:

If we multiply by -i twice, the first multiplication would turn 1 into -i, and the second turns -i into -1. So there’s really two square roots of -1: i and -i.

This is pretty cool. We have some sort of answer, but what does it mean?

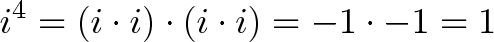

- i is a “new imaginary dimension” to measure a number

- i (or -i) is what numbers “become” when rotated

- Multiplying i is a rotation by 90 degrees counter-clockwise

- Multiplying by -i is a rotation of 90 degrees clockwise

- Two rotations in either direction is -1: it brings us back into the “regular” dimensions of positive and negative numbers.

Numbers are 2-dimensional. Yes, it’s mind bending, just like decimals or long division would be mind-bending to an ancient Roman. (What do you mean there’s a number between 1 and 2?). It’s a strange, new way to think about math.

We asked “How do we turn 1 into -1 in two steps?” and found an answer: rotate it 90 degrees. It’s a strange, new way to think about math. But it’s useful. (By the way, this geometric interpretation of complex numbers didn’t arrive until decades after i was discovered).

Also, keep in mind that having counter-clockwise be positive is a human convention — it easily could have been the other way.

Finding Patterns

Let’s dive into the details a bit. When multiplying negative numbers (like -1), you get a pattern:

- 1, -1, 1, -1, 1, -1, 1, -1

Since -1 doesn’t change the size of a number, just the sign, you flip back and forth. For some number “x”, you’d get:

- x, -x, x, -x, x, -x…

This idea is useful. The number “x” can represent a good or bad hair week. Suppose weeks alternate between good and bad; this is a good week; what will it be like in 47 weeks?

![]()

So -x means a bad hair week. Notice how negative numbers “keep track of the sign” — we can throw (-1)^47 into a calculator without having to count (”Week 1 is good, week 2 is bad… week 3 is good…“). Things that flip back and forth can be modeled well with negative numbers.

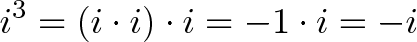

Ok. Now what happens if we keep multiplying by i?

![]()

Very funny. Let’s reduce this a bit:

(No questions here)

(No questions here) (Can’t do much)

(Can’t do much) (That’s what i is all about)

(That’s what i is all about) (Ah, 3 rotations counter-clockwise = 1 rotation clockwise. Neat.)

(Ah, 3 rotations counter-clockwise = 1 rotation clockwise. Neat.) (4 rotations bring us “full circle”)

(4 rotations bring us “full circle”) (Here we go again…)

(Here we go again…)

Represented visually:

We cycle every 4th rotation. This makes sense, right? Any kid can tell you that 4 left turns is the same as no turns at all. Now rather than focusing on imaginary numbers (i, i^2), look at the general pattern:

- X, Y, -X, -Y, X, Y, -X, -Y…

Like negative numbers modeling flipping, imaginary numbers can model anything that rotates between two dimensions “X” and “Y”. Or anything with acyclic, circular relationship — have anything in mind?

‘Cos it’d be a sin if you didn’t. There’ll de Moivre be more in future articles.[Editor’s note: Kalid is in electroshock therapy to treat his pun addiction.]

Understanding Complex Numbers

There’s another detail to cover: can a number be both “real” and “imaginary”?

You bet. Who says we have to rotate the entire 90 degrees? If we keep 1 foot in the “real” dimension and another in the imaginary one, it looks like this:

We’re at a 45 degree angle, with equal parts in the real and imaginary (1 + i). It’s like a hotdog with both mustard and ketchup — who says you need to choose?

In fact, we can pick any combination of real and imaginary numbers and make a triangle. The angle becomes the “angle of rotation”. A complex number is the fancy name for numbers with both real and imaginary parts. They’re written a + bi, where

- a is the real part

- b is the imaginary part

Not too bad. But there’s one last question: how “big” is a complex number? We can’t measure the real part or imaginary parts in isolation, because that would miss the big picture.

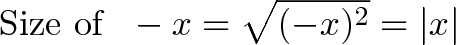

Let’s step back. The size of a negative number is not whether you can count it — it’s the distance from zero. In the case of negatives this is:

Which is another way to find the absolute value. But for complex numbers, how do we measure two components at 90 degree angles?

It’s a bird… it’s a plane… it’s Pythagoras!

Geez, his theorem shows up everywhere, even in numbers invented 2000 years after his time. Yes, we are making a triangle of sorts, and the hypotenuse is the distance from zero:

![]()

Neat. While measuring the size isn’t as easy as “dropping the negative sign”, complex numbers do have their uses. Let’s take a look.

A Real Example: Rotations

We’re not going to wait until college physics to use imaginary numbers. Let’s try them out today. There’s much more to say about complex multiplication, but keep this in mind:

- Multiplying by a complex number rotates by its angle

Let’s take a look. Suppose I’m on a boat, with a heading of 3 units East for every 4 units North. I want to change my heading 45 degrees counter-clockwise. What’s the new heading?

Some hotshot will say “That’s simple! Just take the sine, cosine, gobbledegook by the tangent… fluxsom the foobar… and…“. Crack. Sorry, did I break your calculator? Care to answer that question again?

Let’s try a simpler approach: we’re on a heading of 3 + 4i (whatever that angle is; we don’t really care), and want to rotate by 45 degrees. Well, 45 degrees is 1 + i (perfect diagonal), so we can multiply by that amount!

Here’s the idea:

- Original heading: 3 units East, 4 units North = 3 + 4i

- Rotate counter-clockwise by 45 degrees = multiply by 1 + i

If we multiply them together we get:

So our new orientation is 1 unit West (-1 East), and 7 units North, which you could draw out and follow.

But yowza! We found that out in 10 seconds, without touching sine or cosine. There were no vectors, matrices, or keeping track what quadrant we are in. It wasjust arithmetic with a touch of algebra to cross-multiply. Imaginary numbers have the rotation rules baked in: it just works.

Even better, the result is useful. We have a heading (-1, 7) instead of an angle (atan(7/-1) = 98.13, keeping in mind we’re in quadrant 2). How, exactly, were you planning on drawing and following that angle? With the protractor you keep around?

No, you’d convert it into cosine and sine (-.14 and .99), find a reasonable ratio between them (about 1 to 7), and sketch out the triangle. Complex numbers beat you to it, instantly, accurately, and without a calculator.

If you’re like me, you’ll find this use mind-blowing. And if you don’t, well, I’m afraid math doesn’t toot your horn. Sorry.

Trigonometry is great, but complex numbers can make ugly calculations simple (like calculating cosine(a+b) ). This is just a preview; later articles will give you the full meal.

Aside: Some people think “Hey, it’s not useful to have North/East headings instead of a degree angle to follow!”

Really? Ok, look at your right hand. What’s the angle from the bottom of your pinky to the top of your index finger? Good luck figuring that out on your own.

With a heading, you can at least say “Oh, it’s X inches across and Y inches up” and have some chance of working with that bearing.

Complex Numbers Aren’t

That was a whirlwind tour of my basic insights. Take a look at the first chart — it should make sense now.

There’s so much more to these beautiful, zany numbers, but my brain is tired. My goals were simple:

- Convince you that complex numbers were considered “crazy” but can be useful (just like negative numbers were)

- Show how complex numbers can make certain problems easier, like rotations

If I seem hot and bothered about this topic, there’s a reason. Imaginary numbers have been a bee in my bonnet for years — the lack of an intuitive insight frustrated me.

Now that I’ve finally had insights, I’m bursting to share them. But it frustrates me that you’re reading this on the blog of a wild-eyed lunatic, and not in a classroom. We suffocate our questions and “chug through” — because we don’t search for and share clean, intuitive insights. Egad.

But better to light a candle than curse the darkness: here’s my thoughts, and one of you will shine a spotlight. Thinking we’ve “figured out” a topic like numbers is what keeps us in Roman Numeral land.

There’s much more complex numbers: check out the details of complex arithmetic. Happy math.

Epilogue: But they’re still strange!

I know, they’re still strange to me too. I try to put myself in the mind of the first person to discover zero.

Zero is such a weird idea, having “something” represent “nothing”, and it eluded the Romans. Complex numbers are similar — it’s a new way of thinking. But both zero and complex numbers make math much easier. If we never adopted strange, new number systems, we’d still be counting on our fingers.

I repeat this analogy because it’s so easy to start thinking that complex numbers aren’t “normal”. Let’s keep our mind open: in the future they’ll chuckle that complex numbers were once distrusted, even until the 2000’s.

If you want more nitty-gritty, check out wikipedia, the Dr. Math discussion, or another argument on why imaginary numbers exist.

1157

1157

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?