案例1:重载场景下对子类赋值失败

base_class(父类)和extend_class(子类)内部都有相同的变量int var[$];

父类是参数化类,在test这一层通过uvm的工厂机制进行override(type)后,这个类在env这里被实例化,实例化名refm;

在test的run_phase阶段,赋值:env.refm.var.push_back(99);

发现并没有赋值到子类;把子类的var[$]删掉后,子类才能看到这个push进来的00;

另一个问题是,如果子类加了一个变量,再在test这里对这个变量赋值,会报编译错误,说没有在父类找到这个变量;所以推测,外面在赋值的时候其实是对父类已经声明的变量进行赋值。(需要先把父类句柄转换成子类的,就可以了;仿真查找变量,父类和子类其实在不同的内存空间;后面补充个图)(《system Verilog与功能验证》p141:在访问对象的过程中遵循一下规则:通过父类的对象去引用在子类中重写的属性或方法,结果只会调用父类的属性或方法;通过子类对象可以直接访向重写的属性或方法的在子类扩展过程中新增的属性和方法对于父类对象不可见龙子类可以通过super操作符访向父类中的属性和方法,以区分于本身重写的属性和方法。)

解决办法:code stye完善;父子类不能声明相同名字的变量;

案例2:phase退出,但是后面的phase挂住了;

在main phase阶段去调用寄存器模型的seq去执行一些检查;main phase退出后,在shutdown phase又去调用了这个seq,然后一直挂在seq这里;虽然main phase在tc这里退出去了,seq的线程也终止了,但是seq的状态是处于wait_rsp(pending)状态,这个状态并没有被“复位”;导致在shutdown phase再次调用这个seq时被挂住了(一直等不到main_phase阶段的响应?)

解决办法:

有一些检查可以集中在shutdown phase,不在main phase进行;(不需要在两个地方都检查)

案例3:

Question:

使用Systemverilog,在module中包含其他package出现如下错误:

Error: Unsupported Systemverilog construct

found ‘package’ inside module before ‘endmodule’. ‘package’ inside ‘module’ is not allowed.

Answer:

解决方法如下:

1、有可能是把 include package 写在了module 和 endmodule之间了;需要把 include package写在 module定义之前或endmodule之后;

2、还有一种是在其他模块中少了 endmodule 关键字,这样也会导致这个模块出现这个错误,但实际上不是该模块的问题;

作者: MonkeyPi

链接: https://makerinchina.cn/article_fc3dbcd7a8f2.html

来源: MakerInChina

著作权为原网站(https://makerinchina.cn)所有,转载请注明出处。

解决办法:

案例4:一个用例是被包在package里面,里面不能直接使用force对dut内部信号进行操作。

因为package看不到top_tb的层次结构,所以会报错,路径问题。

解决办法:可以采用uvm_hdl_deposit的方式实现对dut内部信号的操作。

案例5:pre_abort调用导致死循环;

UVM可以设定报错多少个UVM_ERROR后(server.set_max_quit_count(200) ),退出仿真(好像也是通过调用UVM_FATAL实现的),然后会调用各个uvm组件的pre_abort方法,去打印一些信息来辅助debug;但是如果在pre_abort里面加了uvm_error且达到200个的话;会导致死循环,不停的进入pre_abort,出不来;

解决办法:pre_abort方法里面,避免报uvm_error

案例6:uvm_callback两次add,调用的地方使用是第一次add的callback。

随后遇到callback的调用问题,导致一直用的是复位前的share_cq_0的base_addr,之所以会这样是因为调用callback的地方一直在调用原来复位的scq_cb,而这个scq_cb又是指向复位前的scq,导致收到中断后,依旧走的是原来的callback,之所以会这样,应该是和uvm的callback机制有关系;可以看到复位后有两个callback,调用callback的地方一直是用的第一个callback(复位之前add的那个);

解决办法:

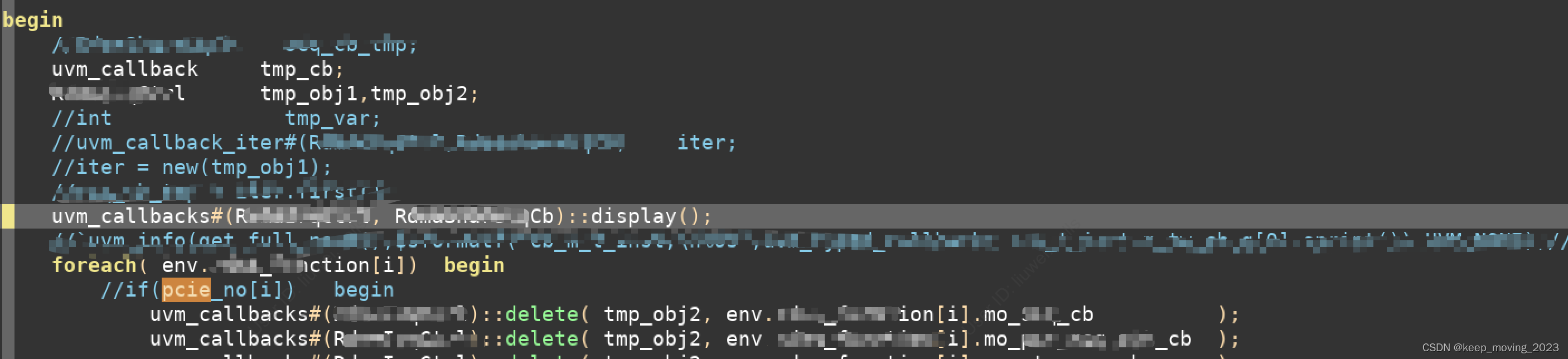

所以考虑要把原来的callback删掉;

但是不好删,因为scq_cb句柄在一个function里面,tc看不到,就不能直接调用下面这个delete去删除旧的scq_cb;所以在rm里面声明了一个句柄保存上一个scq_cb的指针,然后再在tc里面删除;(也可以在rm里面的functuon删除:就是判断一下句柄是否非空;)

callback的打印:

callback的使用流程可参考:UVM——Callback机制(作用、使用步骤实例)_uvm callback-CSDN博客

案例7:

解决办法:

案例8:

解决办法:

案例5:

解决办法:

案例6:

解决办法:

案例7:

解决办法:

案例8:

解决办法:

2972

2972

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?