注:机翻,未校。

social science 社会科学

Written by Liah Greenfeld, Robert A. Nisbet•All

Fact-checked by

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

Last Updated: Jul 25, 2024

Roger Bacon

罗吉尔·培根(英国思想家、科学家)

Top Questions 常见问题

What is a social science? 什么是社会科学?

A social science is any branch of academic study or science that deals with human behaviour in its social and cultural aspects. Usually included within the social sciences are cultural (or social) anthropology, sociology, psychology, political science, and economics.

社会科学是学术研究或科学的任何分支,涉及社会和文化方面的人类行为。社会科学通常包括文化(或社会)人类学、社会学、心理学、政治学和经济学。

What is the relationship between the terms behavioral science and social science? 行为科学和社会科学这两个术语之间有什么关系?

Beginning in the 1950s, the term behavioral sciences was often applied to disciplines categorized as social sciences. Some favored this term because it brought these disciplines closer to some of the sciences, such as physical anthropology, which also deal with human behavior.

从 1950 年代开始,行为科学一词通常适用于被归类为社会科学的学科。有些人喜欢这个词,因为它使这些学科更接近一些科学,例如也处理人类行为的体质人类学。

Who named the social science discipline of sociology? 谁命名了社会学的社会科学学科?

Auguste Comte gave the social science of sociology its name and established the new discipline in a systematic fashion.

奥古斯特·孔德 (Auguste Comte) 以社会学社会科学命名,并以系统的方式建立了这门新学科。

What is cultural anthropology’s relationship to the social sciences? 文化人类学与社会科学有什么关系?

Cultural anthropology is a branch of the social sciences that deals with the study of culture in all of its aspects and that uses the methods, concepts, and data of archaeology, ethnography and ethnology, folklore, and linguistics.

文化人类学是社会科学的一个分支,涉及文化的各个方面的研究,并使用考古学、民族学和民族学、民俗学和语言学的方法、概念和数据。

What was Adolphe Quetelet’s contribution to the social sciences? 阿道夫·奎特莱 (Adolphe Quetelet) 对社会科学的贡献是什么?

Adolphe Quetelet was a key figure in the social statistics branch of the social sciences. He was the first person to call attention, in a systematic manner, to the kinds of structured behavior that could be observed and identified only through statistical means.

阿道夫·奎特莱 (Adolphe Quetelet) 是社会科学社会统计分支的关键人物。他是第一个以系统的方式引起人们对只能通过统计手段观察和识别的结构化行为类型的人。

social science, any branch of academic study or science that deals with human behaviour in its social and cultural aspects. Usually included within the social sciences are cultural (or social) anthropology, sociology, psychology, political science, and economics. The discipline of historiography is regarded by many as a social science, and certain areas of historical study are almost indistinguishable from work done in the social sciences. Most historians, however, consider history as one of the humanities. In the United States, focused programs, such as African-American Studies, Latinx Studies, Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, are, as a rule, also included among the social sciences, as are often Latin American Studies and Middle Eastern Studies, while, for instance, French, German, or Italian Studies are commonly associated with humanities. In the past, Sovietology was always considered a social science discipline, in contrast to Russian Studies.

社会科学,任何涉及社会和文化方面人类行为的学术研究或科学分支。社会科学通常包括文化(或社会)人类学、社会学、心理学、政治学和经济学。史学学科被许多人视为一门社会科学,历史研究的某些领域与社会科学的工作几乎没有区别。然而,大多数历史学家认为历史是人文学科之一。在美国,重点课程,如非裔美国人研究、拉丁裔研究、妇女、性别和性研究,通常也包含在社会科学中,拉丁美洲研究和中东研究也是如此,而法国、德国或意大利研究通常与人文学科有关。过去,苏联学一直被认为是一门社会科学学科,与俄罗斯研究相反。

Beginning in the 1950s, the term behavioral sciences was often applied to the disciplines designated as the social sciences. Those who favoured this term did so in part because these disciplines were thus brought closer to some of the sciences, such as physical anthropology and physiological psychology, which also deal with human behaviour.

从 1950 年代开始,行为科学一词经常被应用于被指定为社会科学的学科。那些赞成这个词的人之所以这样做,部分原因是这些学科因此更接近一些科学,例如物理人类学和生理心理学,它们也涉及人类行为。

Strictly speaking, the social sciences, as distinct and recognized academic disciplines, emerged only on the cusp of the 20th century. But one must go back farther in time for the origins of some of their fundamental ideas and objectives. In the largest sense, the origins go all the way back to the ancient Greeks and their rationalist inquiries into human nature, the state, and morality. The heritage of both Greece and Rome is a powerful one in the history of social thought, as it is in other areas of Western society. Very probably, apart from the initial Greek determination to study all things in the spirit of dispassionate and rational inquiry, there would be no social sciences today. True, there have been long periods of time, as during the Western Middle Ages, when the Greek rationalist temper was lacking. But the recovery of this temper, through texts of the great classical philosophers, is the very essence of the Renaissance and the Enlightenment in modern European history. With the Enlightenment, in the 17th and 18th centuries, one may begin.

严格来说,社会科学作为独特且公认的学科,只是在 20 世纪的风口浪尖才出现。但是,我们必须追溯到更久远的时代,才能了解他们的一些基本思想和目标的起源。从最大的意义上说,起源可以追溯到古希腊人以及他们对人性、国家和道德的理性主义探究。希腊和罗马的遗产在社会思想史上都是强大的,就像在西方社会的其他领域一样。很有可能,除了希腊人最初决心以冷静和理性探究的精神研究所有事物之外,今天不会有社会科学。诚然,在很长一段时间里,就像在西方中世纪一样,希腊的理性主义气质是缺乏的。但是,通过伟大的古典哲学家的著作来恢复这种脾气,是现代欧洲历史上文艺复兴和启蒙运动的精髓。随着启蒙运动的到来,在 17 世纪和 18 世纪,人们可能会开始。

Heritage of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance 中世纪和文艺复兴时期的遗产

Effects of theology 神学的影响

The same impulses that led people in that age to explore Earth, the stellar regions, and the nature of matter led them also to explore the institutions around them: state, economy, religion, morality, and, above all, human nature itself. It was the fragmentation of medieval philosophy and theory, and, with this, the shattering of the medieval worldview that had lain deep in thought until about the 16th century, that was the immediate basis of the rise of the several strands of specialized social thought that were in time to provide the inspiration for the social sciences.

那个时代的人们探索地球、恒星区域和物质本质的相同冲动也促使他们探索周围的制度:国家、经济、宗教、道德,尤其是人性本身。正是中世纪哲学和理论的分裂,以及随之而来的中世纪世界观的瓦解,直到 16 世纪左右,才被深深埋藏在思想中,这就是几个专业社会思想崛起的直接基础,这些思想及时为社会科学提供了灵感。

Medieval theology, especially as it appears in St. Thomas Aquinas’s Summa theologiae (1265/66–1273), contained and fashioned syntheses from ideas about humanity and society—ideas indeed that may be seen to be political, social, economic, anthropological, and geographical in their substance. But it is partly this close relation between medieval theology and ideas of the social sciences that accounts for the different trajectories of the social sciences, on the one hand, and the trajectories of the physical and life sciences, on the other. From the time of the English philosopher Roger Bacon in the 13th century, there were at least some rudiments of physical science that were largely independent of medieval theology and philosophy. Historians of physical science have no difficulty in tracing the continuation of this experimental tradition, primitive and irregular though it was by later standards, throughout the Middle Ages. Side by side with the kinds of experiment made notable by Bacon were impressive changes in technology through the medieval period and then, in striking degree, in the Renaissance. Efforts to improve agricultural productivity; the rising utilization of gunpowder, with consequent development of guns and the problems that they presented in ballistics; growing trade, leading to increased use of ships and improvements in the arts of navigation, including use of telescopes; and the whole range of such mechanical arts in the Middle Ages and Renaissance as architecture, engineering, optics, and the construction of watches and clocks—all of this put a high premium on a pragmatic and operational understanding of at least the simpler principles of mechanics, physics, astronomy, and, in time, chemistry.

中世纪的神学,特别是圣托马斯·阿奎那的《神学大全》(1265/66-1273)中出现的神学,包含并塑造了关于人类和社会的观念的综合——这些思想的实质确实可以被视为政治、社会、经济、人类学和地理学的。但是,在一定程度上,正是中世纪神学和社会科学思想之间的这种密切关系,解释了社会科学与物理科学和生命科学的不同轨迹。从 13 世纪英国哲学家罗杰·培根 (Roger Bacon) 的时代开始,至少有一些物理科学的基本知识在很大程度上独立于中世纪的神学和哲学。物理科学史学家不难追溯这种实验传统的延续,尽管按照后来的标准来看,它是原始的和不规则的,贯穿整个中世纪。与培根所关注的各种实验并列的是中世纪时期令人印象深刻的技术变化,然后是文艺复兴时期的惊人变化。努力提高农业生产力;火药的使用量增加,随之而来的枪支发展以及它们在弹道学中提出的问题;贸易增长,导致船舶使用的增加和航海艺术的改进,包括望远镜的使用;以及中世纪和文艺复兴时期的所有机械艺术,如建筑、工程、光学和钟表的建造——所有这些都高度重视对至少对机械、物理学、天文学以及化学等更简单原理的实用和操作理解。

Copernicus, 17th-century copy of a 16th-century self-portrait; in the Jagiellonian University Museum Collegium Maius, Kraków, Poland.(more)

哥白尼,一幅 16 世纪自画像的 17 世纪复制品;雅盖隆大学博物馆,迈乌斯学院,Kraków,波兰。

Galileo, oil painting by J. Sustermans, c. 1637; in the Uffizi, Florence.

“伽利略,由 J. Sustermans 绘制的油画,约 1637 年;现藏于佛罗伦萨乌菲兹美术馆。”

In short, by the time of Copernicus and Galileo in the 16th century, a fairly broad substratum of physical science existed, largely empirical but not without theoretical implications on which the edifice of modern physical science could be built. It is notable that the empirical foundations of physiology were being established in the studies of the human body being conducted in medieval schools of medicine and, as the career of Leonardo da Vinci so resplendently illustrates, among artists of the Renaissance, whose interest in accuracy and detail of painting and sculpture led to their careful studies of human anatomy.

简而言之,到 16 世纪哥白尼和伽利略的时代,已经存在相当广泛的物理科学基础,主要是实证的,但并非没有理论意义,现代物理科学的大厦可以建立在此基础上。值得注意的是,生理学的实证基础是在中世纪医学院进行的人体研究中建立起来的,正如列奥纳多·达·芬奇 (Leonardo da Vinci) 的职业生涯所充分说明的那样,在文艺复兴时期的艺术家中,他们对绘画和雕塑的准确性和细节的兴趣导致他们对人体解剖学的仔细研究。

Very different was the beginning of the social sciences. In the first place, the Roman Catholic Church, throughout the Middle Ages and even into the Renaissance and Reformation, was much more attentive to what scholars wrote and thought about the human mind and human behaviour in society than it was toward what was being studied and written in the physical sciences. From the church’s point of view, while it might be important to see to it that thought on the physical world corresponded as far as possible to what Scripture said—witnessed, for example, in the famous questioning of Galileo—it was far more important that such correspondence exist in matters affecting the human mind, spirit, and soul. Nearly all the subjects and questions that would form the bases of the social sciences in later centuries were tightly woven into the fabric of medieval Scholasticism, and it was not easy for even the boldest minds to break this fabric.

社会科学的开端非常不同。首先,罗马天主教会,在整个中世纪,甚至到文艺复兴和宗教改革时期,都更加关注学者们关于人类思想和社会行为的著作和思考,而不是物理科学的研究和著作。从教会的角度来看,虽然确保对物质世界的思考尽可能地与圣经所说的相一致可能很重要——例如,在著名的对伽利略的质询中所见证的——但在影响人类思想、精神和灵魂的事情上,这种对应关系的存在要重要得多。几乎所有在后来几个世纪构成社会科学基础的主题和问题都紧紧地编织在中世纪经院哲学的结构中,即使是最大胆的头脑也很难打破这个结构。

Effects of the classics and of Cartesianism 古典主义和笛卡尔主义的影响

Then, when the hold of Scholasticism did begin to wane, two fresh influences, equally powerful, came on the scene to prevent anything comparable to the pragmatic and empirical foundations of the physical sciences from forming in the study of humanity and society. The first was the immense appeal of the Greek classics during the Renaissance, especially those of the philosophers Plato and Aristotle. A great deal of social thought during the Renaissance was little more than gloss or commentary on the Greek classics. One sees this throughout the 15th and 16th centuries.

然后,当经院哲学的控制确实开始减弱时,两种同样强大的新影响出现了,阻止了任何与物理科学的实用主义和实证基础相媲美的东西在人类和社会的研究中形成。首先是文艺复兴时期希腊经典的巨大吸引力,尤其是哲学家柏拉图和亚里士多德的经典作品。文艺复兴时期的大量社会思想只不过是对希腊经典的修饰或评论。人们在整个 15 世纪和 16 世纪都可以看到这一点。

René Descartes

勒内·笛卡尔(法国哲学家、数学家、物理学家,解析几何之父,二元论唯心主义和理性主义代表人物,提出“我思故我在”和“普遍怀疑”的主张,是西方现代哲学奠基人)。

Second, in the 17th century there appeared the powerful influence of the philosopher René Descartes. Cartesianism, as his philosophy was called, declared that the proper approach to understanding of the world, including humanity and society, was through a few simple, fundamental ideas of reality and, then, rigorous, almost geometrical deduction of more complex ideas and eventually of large, encompassing theories, from these simple ideas, all of which, Descartes insisted, were the stock of common sense—the mind that is common to all human beings at birth. It would be hard to exaggerate the impact of Cartesianism on social and political and moral thought during the century and a half following publication of his Discourse on Method (1637) and his Meditations on First Philosophy (1641). Through the Enlightenment into the later 18th century, the spell of Cartesianism was cast on nearly all those who were concerned with the problems of human nature and human society.

其次,在 17 世纪出现了哲学家勒内·笛卡尔 (René Descartes) 的强大影响力。笛卡尔主义,正如他的哲学所称的那样,宣称理解世界(包括人类和社会)的正确方法是通过一些简单的、基本的现实观念,然后,从这些简单的观念中,严格地、几乎是几何学地推导出更复杂的观念,并最终推导出宏大的、包罗万象的理论,笛卡尔坚持认为,所有这些都是常识的存量——所有人类在出生时共有的思想。在他的《论方法》(1637 年)和他的《第一哲学沉思》(1641 年)出版后的一个半世纪里,很难夸大笛卡尔主义对社会、政治和道德思想的影响。从启蒙运动到 18 世纪后期,笛卡尔主义的魔咒几乎被施加在所有关心人性和人类社会问题的人身上。

Great amounts of data pertinent to the study of human behaviour were becoming available in the 17th and 18th centuries. The emergence of nationalism and the associated impersonal state carried with it ever growing bureaucracies concerned with gathering information, chiefly for taxation, census, and trade purposes. The voluminous and widely published accounts of the great voyages that had begun in the 15th century, the records of soldiers, explorers, and missionaries who perforce had been brought into often long and close contact with indigenous and other non-Western peoples, provided still another great reservoir of data. Until the beginning of the 19th century, these and other empirical materials were used, if at all, solely for illustrative purposes in the writings of the social philosophers. Just as in the equally important area of the study of life, no philosophical framework as yet existed to allow for an objective and comprehensive interpretation of these empirical materials. Only in physics could this be done at the time.

在 17 世纪和 18 世纪,大量与人类行为研究相关的数据变得可用。民族主义的出现和与之相关的非个人国家带来了越来越多的官僚机构,他们主要关注收集信息,主要是为了税收、人口普查和贸易目的。对 15 世纪开始的伟大航海的大量广泛出版的描述,以及士兵、探险家和传教士的记录,他们经常与土著和其他非西方人民进行长期而密切的接触,这提供了另一个巨大的数据宝库。直到 19 世纪初,这些和其他实证材料在社会哲学家的著作中仅用于说明目的,如果有的话。就像在生命研究这个同样重要的领域一样,当时还没有哲学框架来允许对这些实证材料进行客观和全面的解释。当时只有在物理学中才能做到这一点。

Heritage of the Enlightenment 启蒙运动的遗产

There is also the fact that, especially in the 18th century, reform and even revolution were often in the air. The purpose of a great many social philosophers was by no means restricted to philosophical, much less scientific, understanding of humanity and society. The dead hand of the Middle Ages seemed to many vigorous minds in western Europe the principal force to be combatted, through critical reason, enlightenment, and, where necessary, major reform or revolution. One may properly account a great deal of this new spirit to the rise of humanitarianism in modern Europe and in other parts of the world and to the spread of literacy, the rise in the standard of living, and the recognition that poverty and oppression need not be the fate of the masses. The fact remains, however, that social reform is, by definition, a pursuit biased toward what the reformer believes to be good and should exist in place of what actually exists and, as such, is different from the pursuit of scientific knowledge of what is. The very fact that for a long time, indeed through a good part of the 19th century, social reform and social science were regarded as basically the same thing could not have helped but retard the development of such knowledge in regard to human behaviour and society.

还有一个事实是,尤其是在 18 世纪,改革甚至革命的空气中经常弥漫着。许多社会哲学家的目的绝不仅限于哲学上的,更不用说科学的,对人性和社会的理解。在西欧许多精力充沛的头脑中,中世纪的死手似乎是需要通过批判理性、启蒙运动以及必要时的重大改革或革命来对抗的主要力量。我们可以恰当地将这种新精神在很大程度上归功于现代欧洲和世界其他地区人道主义的兴起,以及识字率的普及、生活水平的提高,以及认识到贫困和压迫不一定是大众的命运。然而,事实仍然是,根据定义,社会改革是一种偏向于改革者认为是好的、应该存在的东西而不是实际存在的东西的追求,因此,它与追求什么是科学知识不同。事实上,在很长一段时间里,事实上,在 19 世纪的大部分时间里,社会改革和社会科学基本上被视为一回事,这无助于阻碍这种知识在人类行为和社会方面的发展。

It would be wrong to discount the continuity between the social thought of the 17th and 18th centuries and today’s social sciences. The very idea of social science, as the set of rationally deduced principles on the basis of which society was to be organized, appeared then. Second was the rising awareness of the multiplicity and variety of human experience in the world, a result of trade and exploration. Third was the spreading sense of the self-made character of human behaviour in society—that is, its historical or conventional, rather than God-given, nature. What man made once, man could remake numerous times.

忽视 17 世纪和 18 世纪的社会思想与今天的社会科学之间的连续性是错误的。社会科学的理念,作为社会组织所依据的一套理性推论的原则,在那时出现了。其次是人们越来越意识到世界上人类经验的多样性和多样性,这是贸易和探险的结果。第三是人类行为在社会中自我创造的特征的传播——即它的历史或约定俗成的,而不是上帝赋予的本质。人创造一次的东西,人可以无数次地重塑。

Adam Smith, paste medallion by James Tassie, 1787; in the Scottish National Portrait Gallery, Edinburgh.

“亚当·斯密,由詹姆斯·塔西制作的浮雕奖章,1787年;现藏于爱丁堡苏格兰国家肖像画廊。”

To these may be added two specific concepts of the 17th and 18th centuries, which were inherited by the contemporary social sciences. The first was the idea of structure. Having emerged nearly at the same time in the writings of natural and moral philosophers, it was used by Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, and Jean-Jacques Rousseau with reference to the political structure of the state, by the mid-18th century spreading to highlight the economic writings of the physiocrats and Adam Smith. The idea of structure can also be seen in certain works relating to human psychology and, at opposite reach, to the whole of civil society. Conceptions of structure have in many instances, subject only to minor changes, endured in the contemporary social sciences.

除此之外,还可以添加 17 世纪和 18 世纪的两个具体概念,它们被当代社会科学继承。首先是结构的概念。它几乎同时出现在自然哲学家和道德哲学家的著作中,托马斯·霍布斯、约翰·洛克和让-雅克·卢梭将其用于指代国家的政治结构,到 18 世纪中叶传播开来,以突出重农学家和亚当·斯密的经济著作。结构的概念也可以在某些与人类心理学有关的著作中看到,反之,也可以看到整个公民社会。在许多情况下,结构的概念在当代社会科学中经久不衰,只受到微小的变化。

The second major concept was that of developmental change. Its ultimate roots in Western thought, like those indeed of the whole idea of structure, go back to the Greeks, if not earlier. But it is in the 18th century, above all others, that the philosophy of developmentalism took shape, forming a preview, so to speak, of the social evolutionism of the next century. What was said by such writers as Condorcet, Rousseau, and Smith was that the present is an outgrowth of the past, the result of a long line of development in time, and, furthermore, a line of development that has been caused not by God or fortuitous factors but by conditions and causes immanent in human society. Despite a fairly widespread belief that the idea of social development is a product of prior discovery of biological evolution, the facts are the reverse. Well before any clear idea of genetic speciation existed in European biology, there was a very clear idea of what might be called social speciation—that is, the emergence of one institution from another in time and of the whole differentiation of function and structure that goes with this emergence.

第二个主要概念是发展变化。它在西方思想中的最终根源,就像整个结构思想一样,如果不是更早的话,可以追溯到希腊人。但正是在 18 世纪,发展主义哲学首先形成,可以说是下个世纪社会进化主义的预演。孔多塞、卢梭和斯密等作家所说的是,现在是过去的产物,是时间长线发展的结果,而且,这条发展路线不是由上帝或偶然因素引起的,而是由人类社会内在的条件和原因引起的。尽管人们相当普遍地认为社会发展的想法是先前发现生物进化的产物,但事实恰恰相反。早在欧洲生物学中存在任何明确的遗传物种形成概念之前,就已经有一个非常明确的概念,即所谓的社会物种形成——即一个机构在时间上从另一个机构中出现,以及伴随这种出现的功能和结构的整体分化。

As has been suggested, these and other seminal ideas were contained for the most part in writings whose primary function was to attack the existing order of government and society in western Europe. Another way of putting the matter is to say that these ideas were clear and acknowledged parts of political and social idealism—using that word in its largest sense. Hobbes, Locke, Rousseau, Montesquieu, Smith, and other major philosophers had as vivid and energizing a sense of the ideal—the ideal state, the ideal economy, the ideal civil society—as any earlier utopian writer. These thinkers were, without exception, committed to visions of the good or ideal society. Their interest in the “natural”—that is, natural morality, religion, economy, or education, in contrast to the merely conventional and historically derived—sprang as much from the desire to hold a mirror up to a surrounding society that they disliked as from any dispassionate urge simply to find out what humanity and society are made of. These 17th- and 18th-century ideas were to prove decisive in the 19th and later centuries, so far as the social sciences were concerned.

如前所述,这些和其他开创性思想大部分包含在主要功能是攻击西欧现有政府和社会秩序的著作中。另一种说法是说,这些思想是政治和社会理想主义的明确和公认的部分——用这个词来概括它的最大意义。霍布斯、洛克、卢梭、孟德斯鸠、斯密和其他主要哲学家对理想——理想状态、理想经济、理想公民社会——的感受与任何早期的乌托邦作家一样生动而充满活力。这些思想家无一例外地致力于美好或理想社会的愿景。他们对“自然”的兴趣——即自然道德、宗教、经济或教育,而不是仅仅传统和历史衍生的东西——既源于为他们所不喜欢的周围社会举一面镜子的愿望,也源于任何纯粹想找出人性和社会是由什么组成的冷静的冲动。就社会科学而言,这些 17 世纪和 18 世纪的思想在 19 世纪和以后的世纪被证明是决定性的。

The 19th century 19 世纪

The fundamental ideas, themes, and problems of social thought in the 19th century are best understood as responses to the problem of order that was created in people’s minds by the weakening of the old order, or European society, under the twin blows of the French Revolution and the Industrial Revolution. The breakup of the old order—an order that had rested on kinship, land, social class, religion, local community, and monarchy—set free, as it were, the complex elements of status, authority, and wealth that had been for so long consolidated. In the same way that the history of 19th-century politics, industry, and trade is basically about the practical efforts of human beings to reconsolidate these elements, so the history of 19th-century social thought is about theoretical efforts to reconsolidate them—that is, to give them new contexts of meaning.

19 世纪社会思想的基本思想、主题和问题最好理解为对在法国大革命和工业革命的双重打击下,旧秩序或欧洲社会的削弱在人们心中创造的秩序问题的回应。旧秩序——一种建立在亲属关系、土地、社会阶层、宗教、地方社区和君主制之上的秩序——的瓦解,仿佛解放了长期巩固的地位、权威和财富的复杂元素。就像 19 世纪的政治、工业和贸易史基本上是关于人类重新整合这些元素的实际努力一样,19 世纪社会思想的历史也是关于重新整合它们的理论努力——也就是说,赋予它们新的意义背景。

In terms of the immediacy and sheer massiveness of impact on human thought and values, it would be difficult to find revolutions of comparable magnitude in human history. The political, social, and cultural changes that began in France and England at the very end of the 18th century spread almost immediately through Europe and the Americas in the 19th century and then on to Asia, Africa, and Oceania in the 20th. The effects of the two revolutions, the one overwhelmingly democratic in thrust, the other industrial-capitalist, have been to undermine, shake, or topple institutions that had endured for centuries, even millennia, and with them systems of authority, status, belief, and community.

就对人类思想和价值观的直接性和巨大影响而言,在人类历史上很难找到同等规模的革命。18 世纪末始于法国和英国的政治、社会和文化变革几乎立即蔓延到 19 世纪的欧洲和美洲,然后在 20 世纪蔓延到亚洲、非洲和大洋洲。这两次革命的影响,一场是压倒性的民主革命,另一场是工业资本主义革命,破坏、动摇或推翻了持续了几个世纪甚至几千年的制度,以及随之而来的权威、地位、信仰和社区制度。

It is easy today to deprecate the suddenness, the cataclysmic nature, the overall revolutionary effect of these two changes and to seek to subordinate results to longer, deeper tendencies of more gradual change in western Europe. But as many historians have pointed out, there was to be seen, and seen by a great many sensitive minds of that day, a dramatic and convulsive quality to the changes that cannot properly be subsumed to the slower processes of continuous evolutionary change. What is crucial, in any event, from the point of view of the history of the social thought of the period, is how the changes were actually envisaged at the time. By a large number of social philosophers as well as novelists, in all spheres, those changes were regarded as nothing less than earth-shattering.

今天,人们很容易贬低这两项变化的突然性、灾难性性质和整体革命性影响,并试图将结果服从于西欧更长期、更深刻的变化趋势。但正如许多历史学家所指出的,在那个时代,许多敏感的头脑所看到的,是那些变化的戏剧性和令人痉挛的品质,而这种变化不能被适当地归入持续进化变化的较慢过程。无论如何,从那个时期的社会思想历史的角度来看,至关重要的是当时实际如何设想这些变化。许多社会哲学家和小说家在各个领域都认为这些变化无异于惊天动地。

The coining or redefining of words is an excellent indication of people’s perceptions of change in a given historical period. A large number of words taken for granted today came into being in the period marked by the final decade or two of the 18th century and the first quarter of the 19th. Among these are: industry, industrialist, democracy, class, middle class, ideology, intellectual, rationalism, humanitarian, atomistic, masses, commercialism, proletariat, collectivism, equalitarian, liberal, conservative, scientist, utilitarian, bureaucracy, capitalism, and crisis. Some of these words were invented; others reflect new and very different meanings given to old ones. All alike bear witness to the transformed character of the European social landscape as this landscape loomed up to the leading minds of the age. And all these words bear witness too to the emergence of new social philosophies and, most pertinent to the subject of this article, the social sciences as they are known today.

词语的创造或重新定义是人们对特定历史时期变化的看法的极好表现。大量今天被认为是理所当然的词语是在 18 世纪的最后十年或二十年和 19 世纪上半年出现的。其中包括:工业、实业家、民主、阶级、中产阶级、意识形态、知识分子、理性主义、人道主义、原子主义、大众、商业主义、无产阶级、集体主义、平等主义、自由主义、保守主义、科学家、功利主义、官僚主义、资本主义和危机。其中一些词是发明的;另一些则反映了赋予旧 Ones 的新含义和截然不同的含义。所有这些都见证了欧洲社会景观的转变特征,因为这种景观对那个时代的主导思想来说迫在眉睫。所有这些话也见证了新社会哲学的出现,以及与本文主题最相关的是今天所熟知的社会科学。

Major themes resulting from democratic and industrial change 民主和工业变革产生的主要主题

It is illuminating to mention a few of the major themes in social thought in the 19th century that were almost the direct results of the democratic and industrial revolutions. It should be borne in mind that these themes are to be seen in the philosophical and literary writing of the age as well as in social thought narrowly defined.

提到 19 世纪社会思想中的几个主要主题,这些主题几乎是民主革命和工业革命的直接结果,这很有启发性。应该记住,这些主题可以在那个时代的哲学和文学作品以及狭义的社会思想中看到。

Thomas Robert Malthus, detail of an engraving after a portrait by J. Linnell, 1833.

“托马斯・罗伯特・马尔萨斯,依据 J. Linnell 的肖像所作的雕刻细节,1833 年。”

First, there was the great increase in population. Between 1750 and 1850 the population of Europe went from 140 million to 266 million and of the world from 728 million to well over 1 billion. It was an English clergyman and moral philosopher (considered economist), Thomas Malthus, who, in his famous Essay on the Principle of Population (1798), first marked the enormous significance to human welfare of this increase. With the diminution of historic checks on population growth, chiefly those of high mortality rates—a diminution that was, as Malthus realized, one of the rewards of technological progress—there were no easily foreseeable limits to growth of population. And such growth, he stressed, could only upset the traditional balance between population, which Malthus described as growing at a geometrical rate, and food supply, which he declared could grow only at an arithmetical rate. Not all social thinkers in the century took the pessimistic view of the matter that Malthus did, but few if any were indifferent to the impact of explosive increase in population on economy, government, and society.

首先,人口大幅增长。1750 年至 1850 年间,欧洲人口从 1.4 亿增加到 2.66 亿,世界人口从 7.28 亿增加到超过 10 亿。英国神职人员和道德哲学家(被认为是经济学家)托马斯·马尔萨斯 (Thomas Malthus) 在他著名的《人口原理论文》(1798 年)中首次指出了这种增长对人类福利的巨大意义。随着历史上对人口增长的制约减少,主要是那些对高死亡率的制约——正如马尔萨斯所意识到的那样,这种减少是技术进步的回报之一——人口增长没有容易预见的限制。他强调,这种增长只会打破人口和粮食供应之间的传统平衡,马尔萨斯将其描述为以几何速度增长,而粮食供应只能以算术速度增长。本世纪并非所有社会思想家都像马尔萨斯那样对这个问题持悲观态度,但很少有人对人炸性增长对经济、政府和社会的影响无动于衷。

Second, there was the condition of labour. It may be possible to see this condition in the early 19th century as in fact better than the condition of the rural masses at earlier times. But the important point is that to a large number of writers in the 19th century it seemed worse and was defined as worse. The wrenching of large numbers of people from the older and protective contexts of village, guild, parish, and family, and their massing in the new centres of industry, forming slums, living in common squalor and wretchedness, their wages generally behind cost of living, their families growing larger, their standard of living becoming lower, as it seemed—all of this is a frequent theme in the literature and social thought of the century. Economic thought indeed became known as the “dismal science,” because writers who focused on economic matters, from David Ricardo to Karl Marx, could see little likelihood of the condition of labour improving under capitalism.

其次是劳动条件。在 19 世纪初,我们可能可以看到这种状况实际上比早期农村群众的状况要好。但重要的一点是,对于 19 世纪的许多作家来说,它似乎更糟,并被定义为更糟。大批人从村庄、行会、教区和家庭等古老的保护环境中被赶走,他们聚集在新的工业中心,形成贫民窟,生活在共同的肮脏和悲惨中,他们的工资通常落后于生活成本,他们的家庭越来越大,他们的生活水平越来越低,就像看起来一样——所有这些都是本世纪文学和社会思想中经常出现的主题。经济思想确实被称为“令人沮丧的科学”,因为从大卫·李嘉图到卡尔·马克思,专注于经济问题的作家们都认为在资本主义制度下劳动状况改善的可能性很小。

Third, there was the transformation of property. Not only was more and more property to be seen as industrial—manifest in the factories, business houses, and workshops of the period—but also the very nature of property was changing. Whereas for most of the history of humankind property had been “hard,” visible only in concrete possessions—land and money—now the more intangible kinds of property such as shares of stock, negotiable equities of all kinds, and bonds were assuming ever greater influence in the economy. This led, as was early realized, to the dominance of financial interests, to speculation, and to a symbolic widening of the gulf between the propertied and the masses in the popular imagination (e.g., the former being represented as fat, the latter as thin). The change in the character of property obscured the similarities between the rich and the poor and encouraged thinking about the concentration of property, the accumulation of immense wealth in the hands of a relative few, and, not least, the possibility of economic domination of politics and culture. It should not be thought that only socialists saw property in this light. From Edmund Burke through Auguste Comte, Frédéric Le Play, and John Stuart Mill to Marx, Max Weber, and Émile Durkheim, one finds conservatives and liberals looking at the impact of this change in analogous ways.

第三,财产的转型。不仅越来越多的财产被视为工业财产(体现在那个时期的工厂、商业场所和车间)上,而且财产的性质也在发生变化。在人类历史的大部分时间里,财产是“坚硬的”,只体现在具体的财产——土地和金钱——而现在,更无形的财产种类,如股票、各种可转让股票和债券,在经济中的影响越来越大。正如人们早就意识到的那样,这导致了经济利益的主导地位、投机以及大众想象中有产者和大众之间的鸿沟的象征性扩大(例如,前者被描绘成胖子,后者被描绘成瘦子)。财产性质的变化掩盖了富人和穷人之间的相似之处,并鼓励人们思考财产的集中、巨额财富在相对少数人手中的积累,以及同样重要的是,政治和文化的经济主导的可能性。我们不应该认为只有社会主义者才能从这个角度看待财产。从埃德蒙·伯克(Edmund Burke)到奥古斯特·孔德(Auguste Comte)、弗雷德里克·勒普莱(Frédéric Le Play)和约翰·斯图亚特·穆勒(John Stuart Mill),再到马克思、马克斯·韦伯(Max Weber)和埃米尔·涂尔干(Émile Durkheim),人们发现保守派和自由派都以类似的方式看待这一变化的影响。

Fourth, there was urbanization—the sudden increase in the number of towns and cities in western Europe and the increase in number of persons living in the historic towns and cities. Whereas in earlier centuries, the city had been regarded almost uniformly as a setting of civilization, culture, and freedom of mind, now one found more and more writers aware of the other side of cities: the atomization of human relationships, broken families, the sense of the mass, of anonymity, alienation, and disrupted values. Sociology particularly among the social sciences was to turn its attention to the problems of urbanization. The contrast between the seemingly natural type of community found in rural areas and the seemingly artificial individualistic society of the cities is a basic contrast in sociology, one that was given much attention by such European thinkers as the French sociologists Le Play and Durkheim; the German sociologists Ferdinand Tönnies, Georg Simmel, and Weber; the Belgian statistician Adolphe Quetelet; and, in America, the sociologists Charles H. Cooley and Robert E. Park.

第四,城市化——西欧城镇数量的突然增加,以及居住在历史悠久的城镇的人数增加。在前几个世纪,这座城市几乎一致地被视为文明、文化和思想自由的场所,而现在,人们发现越来越多的作家意识到城市的另一面:人际关系的原子化、破碎的家庭、大众感、匿名感、疏离感和价值观的破坏。社会学,尤其是社会科学中的社会学,将注意力转向城市化问题。农村地区看似自然的社区类型与城市中看似人为的个人主义社会之间的对比是社会学中的一个基本对比,法国社会学家勒普莱和涂尔干等欧洲思想家对此给予了极大的关注;德国社会学家费迪南德·托尼斯(Ferdinand Tönnies)、格奥尔格·西梅尔(Georg Simmel)和韦伯(Weber);比利时统计学家阿道夫·奎特莱特(Adolphe Quetelet);在美国,社会学家查尔斯·库利(Charles H. Cooley)和罗伯特·帕克(Robert E. Park)。

Fifth, there was technology. With the spread of mechanization, first in the factories and then in agriculture, social thinkers could see possibilities of a rupture of the historic relation between humans and nature, between humans and humans, and even between humans and God. To thinkers as politically different as Thomas Carlyle and Marx, technology seemed to lead to dehumanization of the worker and to a new kind of tyranny over human life. Marx, though, far from despising technology, thought the advent of socialism would counteract all this. Alexis de Tocqueville declared that technology, and especially technical specialization of work, was more degrading to the human mind and spirit than even political tyranny. It was thus in the 19th century that the opposition to technology on moral, psychological, and aesthetic grounds first made its appearance in Western thought.

第五,有技术。随着机械化的普及,首先是在工厂,然后是农业,社会思想家可以看到人类与自然之间、人与人之间、甚至人与上帝之间的历史关系破裂的可能性。对于像托马斯·卡莱尔和马克思这样政治不同的思想家来说,技术似乎导致了工人的非人化和对人类生活的一种新型暴政。然而,马克思非但没有鄙视技术,反而认为社会主义的到来会抵消这一切。亚历克西斯·德·托克维尔 (Alexis de Tocqueville) 宣称,技术,尤其是工作的技术专业化,甚至比政治暴政更能降低人类的思想和精神。因此,在 19 世纪,基于道德、心理和审美理由对技术的反对首次出现在西方思想中。

Sixth, there was the factory system. The importance of this to 19th-century thought has been intimated above. Suffice it to add that along with urbanization and spreading mechanization, the system of work whereby masses of workers left home and family to work long hours in the factories became a major theme of social thought as well as of social reform.

第六,工厂制度。这对 19 世纪思想的重要性已在上文中阐明。只需补充一点,随着城市化和机械化的普及,大量工人离开家庭在工厂长时间工作的工作制度成为社会思想和社会改革的主要主题。

Alexis de Tocqueville, detail of an oil painting by Théodore Chassériau, 1850; in the Château de Versailles.(more)

“亚历克西·德·托克维尔,出自泰奥多尔·查塞里奥的油画细节,1850 年;现藏于凡尔赛宫。”

Seventh, and finally, mention is to be made of the development of political masses—that is, the slow but inexorable widening of franchise and electorate through which ever larger numbers of persons became aware of themselves as voters and participants in the political process. This too is a major theme in social thought, to be seen most luminously perhaps in Tocqueville’s Democracy in America (1835–40), a classic work that took not merely America but democracy everywhere as its subject. Tocqueville saw the rise of the political masses, more especially the immense power that could be wielded by the masses, as the single greatest threat to individual freedom and cultural diversity in the ages ahead.

第七,也是最后一点,要提到政治群众的发展——也就是说,选举权和选民的缓慢但不可阻挡的扩大,通过这种扩大,越来越多的人开始意识到自己是政治进程的选民和参与者。这也是社会思想中的一个主要主题,托克维尔的《美国的民主》(1835-40 年)也许最为突出地体现出来,这是一部经典著作,不仅以美国为主题,而且以各地的民主为主题。托克维尔将政治群众的崛起,尤其是群众可能拥有的巨大权力视为未来时代对个人自由和文化多样性的最大威胁。

These, then, are the principal themes in the 19th-century writing that may be seen as direct results of the two great revolutions. As themes, they are to be found not only in social thought but, as noted above, in a great deal of the philosophical and literary writing of the century. In their respective ways, the philosophers Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Ralph Waldo Emerson were as struck by the consequences of the revolutions as were any specifically social thinkers. So too were such novelists as Honoré de Balzac and Charles Dickens.

因此,这些是 19 世纪写作的主要主题,可以被视为两次伟大革命的直接结果。作为主题,它们不仅存在于社会思想中,而且如上所述,存在于本世纪的许多哲学和文学作品中。哲学家乔治·威廉·弗里德里希·黑格尔(Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel)、塞缪尔·泰勒·柯勒律治(Samuel Taylor Coleridge)和拉尔夫·沃尔多·爱默生(Ralph Waldo Emerson)以他们各自的方式,与任何特定的社会思想家一样,都对革命的后果感到震惊。奥诺雷·德·巴尔扎克 (Honoré de Balzac) 和查尔斯·狄更斯 (Charles Dickens) 等小说家也是如此。

New ideologies 新的意识形态

~

Matthew Arnold, detail of an oil painting by G.F. Watts; in the National Portrait Gallery, London.

“马修·阿诺德,出自G.F. 瓦茨的油画细节;现藏于伦敦国家肖像画廊。”(英国诗人、评论家。)

One other point must be emphasized about these themes. They became, almost immediately in the 19th century, the bases of new ideologies. How people reacted to the currents of democracy and industrialism stamped them conservative, liberal, or radical. On the whole, with rarest exceptions, liberals welcomed the two revolutions, seeing in their forces opportunity for freedom and welfare never before known to humankind. The liberal view of society was overwhelmingly democratic, capitalist, industrial, and, of course, individualistic. The case is somewhat different with conservatism and radicalism in the century. Conservatives, beginning with Burke and continuing through Hegel and Matthew Arnold to such minds as John Ruskin later in the century, disliked both democracy and industrialism, preferring the kind of tradition, authority, and civility that had been, in their minds, displaced by the two revolutions. Theirs was a retrospective view, but it was a nonetheless influential one, affecting a number of the leading thinkers of the century, among them Comte and Tocqueville and later Weber and Durkheim. The radicals accepted democracy but only in terms of its extension to all areas of society and its eventual annihilation of any form of authority that did not spring directly from the people as a whole. And although the radicals, for the most part, accepted the phenomenon of industrialism, especially technology, they were uniformly antagonistic to capitalism.

关于这些主题,必须强调另一点。它们几乎立即在 19 世纪成为新意识形态的基础。人们对民主和工业主义潮流的反应使他们被打上了保守、自由或激进的烙印。总的来说,除了极少数例外,自由主义者欢迎这两次革命,在他们的力量中看到了人类前所未有的自由和福利的机会。自由主义的社会观压倒性地是民主、资本主义、工业化,当然还有个人主义。本世纪的保守主义和激进主义的情况有些不同。保守派,从伯克开始,一直到黑格尔和马修·阿诺德,再到本世纪后期的约翰·罗斯金等思想家,都不喜欢民主和工业主义,更喜欢在他们心目中被两次革命取代的那种传统、权威和文明。他们的观点是回顾性的,但它仍然是一个有影响力的观点,影响了本世纪许多领先的思想家,其中包括孔德和托克维尔,以及后来的韦伯和涂尔干。激进分子接受了民主,但仅限于将其扩展到社会的所有领域,并最终消灭了任何不是直接来自全体人民的权威。尽管激进分子在很大程度上接受了工业主义现象,尤其是技术,但他们始终反对资本主义。

These ideological consequences of the two revolutions proved extremely important to social thought, for it would be difficult to identify an intellectual in the century—whether a philosopher or a writer—who was not, in some degree at least, caught up in ideological currents. In referring to proto-sociologists such as Henri de Saint-Simon, Comte, and Le Play; to proto-economists such as Ricardo, Jean-Baptiste Say, and Marx; to proto-political scientists such as Bentham and John Austin; and even to anthropologists like Edward B. Tylor and Lewis Henry Morgan, one has before one persons who were engaged not merely in the study of society but also in often strongly partisan ideology. Some were liberals, some conservatives, others radicals. All drew from the currents of ideology that had been generated by the two great revolutions.

事实证明,两次革命的这些意识形态后果对社会思想极为重要,因为很难确定本世纪的知识分子——无论是哲学家还是作家——至少在某种程度上没有被意识形态潮流所困。在提到原始社会学家,如亨利·德·圣西蒙、孔德和勒普莱;到李嘉图、让-巴蒂斯特·萨伊和马克思等原始经济学家;到原始政治学家,如 Bentham 和 John Austin;甚至对于像爱德华·泰勒(Edward B. Tylor)和刘易斯·亨利·摩根(Lewis Henry Morgan)这样的人类学家来说,在他们之前的人不仅从事社会研究,而且往往参与强烈的党派意识形态研究。有些人是自由派,有些人是保守派,有些人是激进派。所有这些都来自两次大革命产生的意识形态潮流。

New intellectual and philosophical tendencies 新的知识和哲学倾向

It is important also to identify three other powerful tendencies of thought that influenced all of the social sciences. The first is a positivism that was not merely an appeal to science but almost reverence for science; the second, humanitarianism; the third, the philosophy of evolution.

确定影响所有社会科学的其他三种强大的思想趋势也很重要。首先是一种实证主义,它不仅是对科学的诉求,而且几乎是对科学的崇敬;第二种是人道主义;第三个是进化论的哲学。

The positivist appeal of science was to be seen everywhere. The 19th century saw the virtual institutionalization of this ideal—possibly even canonization. The great aim was that of dealing with moral values, institutions, and all social phenomena through the same fundamental methods that could be seen so luminously in physics and, after Darwin, in biology. Prior to the 19th century, no very clear distinction had been made between philosophy and science, and the term philosophy was even preferred by those working directly with physical materials, seeking laws and principles in the fashion of Sir Isaac Newton or William Harvey—that is, by persons whom one would now call scientists.

科学的实证主义吸引力无处不在。19 世纪见证了这种理想的虚拟制度化——甚至可能是圣典化。其伟大目标是通过相同的基本方法来处理道德价值观、制度和所有社会现象,这些方法在物理学和达尔文之后的生物学中可以如此耀眼地看到。在 19 世纪之前,哲学和科学之间并没有非常明确的区别,那些直接与物理材料打交道的人甚至更喜欢哲学这个词,他们以艾萨克·牛顿爵士或威廉·哈维的方式寻求规律和原则——也就是说,我们现在被称为科学家的人。

Auguste Comte, drawing by Tony Toullion, 19th century; in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris.

“奥古斯特·孔德,托尼·图利翁创作的画作,19 世纪;现藏于巴黎国家图书馆。”

In the 19th century, in contrast, the distinction between philosophy and science became an overwhelming one. Virtually every area of human thought and behaviour was considered by a rising number of persons to be amenable to scientific investigation in precisely the same degree that physical data were. More than anyone else, it was Comte who heralded the idea of the scientific treatment of social behaviour. His Cours de philosophie positive (published in English as The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte), published in six volumes between 1830 and 1842, sought to demonstrate irrefutably not merely the possibility but the inevitability of a science of humanity, one for which Comte eventually suggested the word sociology and that would do for humanity as an aspect of reality exactly what biology had already done for individual humans as biological organisms.

相比之下,在 19 世纪,哲学和科学之间的区别变得压倒性。实际上,越来越多的人认为人类思想和行为的每一个领域都适合进行科学研究,其程度与物理数据完全相同。孔德比任何人都更能预示着科学处理社会行为的理念。他的 Cours de philosophie positive(英文出版为 The Positive Philosophy of Auguste Comte)在 1830 年至 1842 年间出版了六卷,旨在无可辩驳地证明一门关于人类的科学不仅存在可能性,而且是必然性的,为此,孔德最终提出了社会学一词,它将对人类作为现实的一个方面产生影响,就像生物学已经对作为生物有机体的个体人类所做的那样。

Humanitarianism, though a very distinguishable current of thought in the century, was closely related to the idea of a science of society. The ultimate purpose of social science was thought by almost everyone to be the welfare of society, the improvement of its moral and social condition. Humanitarianism, strictly defined, is the institutionalization of compassion; it is the extension of welfare and succour from the limited areas in which these had historically been found, chiefly family, village, and the church, to society at large. One of the most notable and also distinctive aspects of the 19th century was the constantly rising number of persons, almost wholly from the new middle class, who worked directly for the betterment of society. In the many projects and proposals for relief of the destitute, improvement of slums, amelioration of the plight of the insane, the indigent, and imprisoned, and other afflicted minorities could be seen the spirit of humanitarianism at work. All kinds of associations were formed, including temperance associations, groups and societies for the abolition of slavery and of poverty and for the improvement of literacy, among other objectives. Nothing like the 19th-century spirit of humanitarianism had ever been seen before in western Europe—not even in France during the Enlightenment, where interest in humankind’s salvation tended to be more intellectual than humanitarian in the strict sense. Humanitarianism was the guiding spirit of the 19th century social reform and, as noted earlier, social reform and social science were regarded as identical. All that helped the cause of the one could be seen as helpful to the other.

人道主义虽然是本世纪非常独特的思潮,但与社会科学的理念密切相关。几乎每个人都认为社会科学的最终目的是社会的福利,改善社会的道德和社会状况。严格定义的人道主义是同情心的制度化;它是福利和救助从历史上发现这些的有限领域(主要是家庭、村庄和教会)延伸到整个社会。19 世纪最值得注意和最独特的方面之一是人数不断增加,他们几乎全部来自新的中产阶级,他们直接为改善社会而努力。在许多救济贫困者、改善贫民窟、改善精神病人、贫困者、被监禁者和其他受苦的少数群体的困境的项目和提案中,可以看到人道主义精神在发挥作用。成立了各种协会,包括节制协会、废除奴隶制和贫困以及提高识字率等目标的团体和社团。19世纪的人道主义精神在西欧从未见过——甚至在启蒙运动时期的法国也没有,那里对人类救赎的兴趣往往更像是知识性的,而不是严格意义上的人道主义。人道主义是 19 世纪社会改革的指导精神,如前所述,社会改革和社会科学被认为是相同的。所有有助于一方事业的事物都可以被视为对另一方有益。

Herbert Spencer

赫伯特·斯宾塞(英国著名的哲学家、社会学家和教育家)

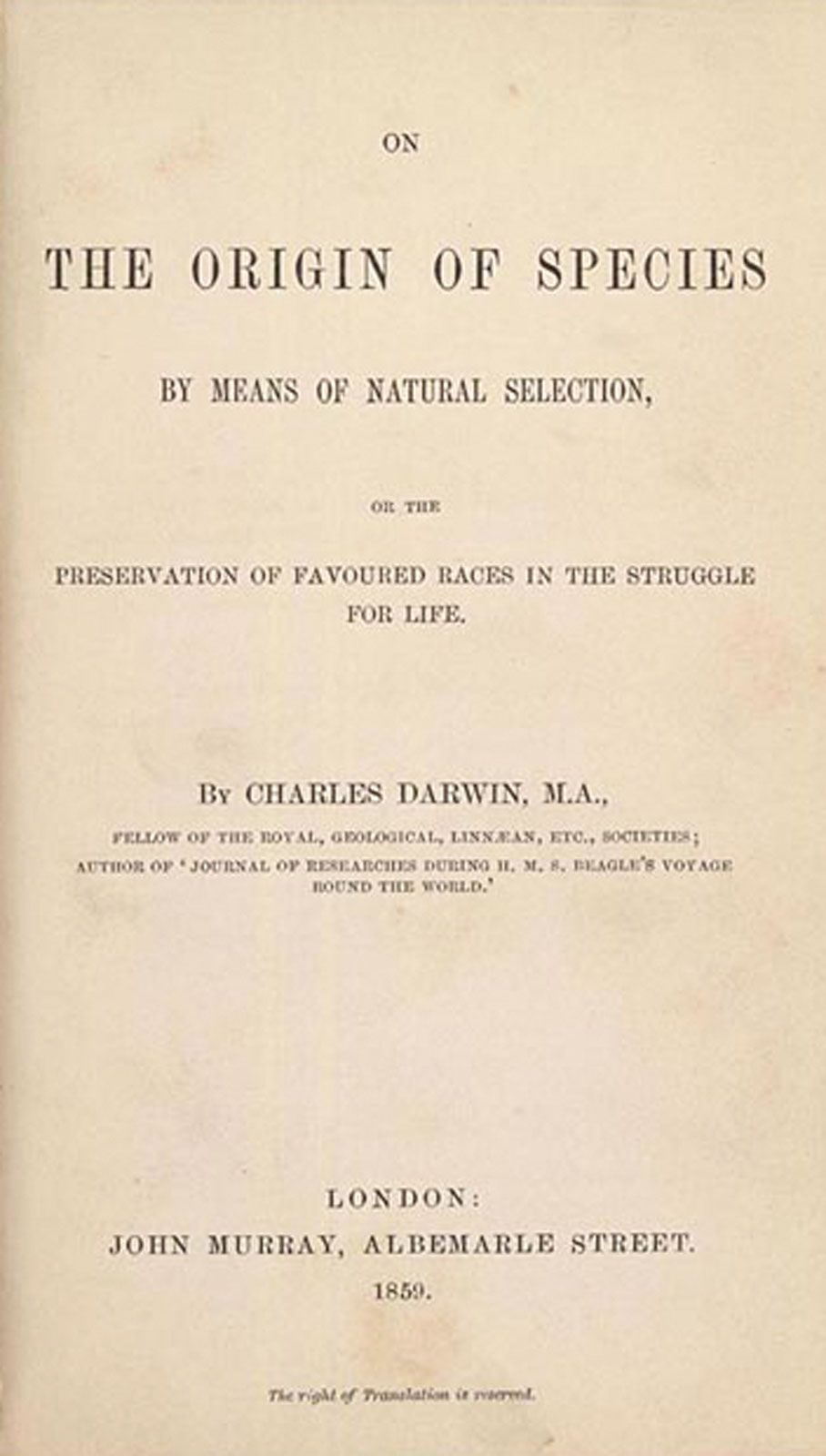

The third of the intellectual influences is that of evolution. It was to affect every one of the social sciences, each of which was as much concerned with the development of things as with their structures. An interest in development was to be found in the 18th century, as noted earlier. But this interest was small and specialized compared with 19th-century theories of social evolution. The impact of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, published in 1859, was of course great and further enhanced the appeal of the evolutionary view of things. But it is very important to recognize that ideas of social evolution had their own origins and contexts and that Darwin’s theory was fundamentally misinterpreted by most social thinkers. The evolutionary works of such influential authors as Comte, Herbert Spencer, and Marx had been completed, or well begun, before publication of Darwin’s work and were Linnaen, that is, first, assuming inheritance of acquired characteristics and unilinear progressive development from simpler and less durable to more complex and more durable forms of life; and, second, classificatory or descriptive in nature, organizing and cataloguing data but offering little in terms of understanding. The important point, in any event, is that the idea or the philosophy of evolution was in the air throughout the century and was profoundly contributory to the idea of sociology as a science similar to such fields as geology, astronomy, and biology. Evolution was as permeative and confusing an idea as the Trinity had been in medieval Europe. Darwin both completely transformed it and endowed it with an immense authority, making evolution coterminous with science. Social scientists would claim this authority, though very few of them would be aware of the transformation which it reflected.

第三个智力影响是进化的影响。它影响了每一门社会科学,每门社会科学都同样关注事物的发展和它们的结构。如前所述,18 世纪人们对发展产生了兴趣。但与 19 世纪的社会进化理论相比,这种兴趣很小而且很专业。查尔斯·达尔文 (Charles Darwin) 于 1859 年出版的《物种起源》(On the Origin of Species) 的影响当然是巨大的,它进一步增强了进化论对事物的看法的吸引力。但是,认识到社会进化论的思想有其自身的起源和背景,而达尔文的理论从根本上被大多数社会思想家误解了,这一点非常重要。孔德、赫伯特·斯宾塞和马克思等有影响力的作家的进化论著作在达尔文的著作出版之前就已经完成或开始了,它们是林南,也就是说,首先,假设后天特征的遗传和从更简单、更不持久的生命形式到更复杂、更持久的生命形式的单线性渐进发展;第二种,本质上是分类或描述性的,组织和编目数据,但在理解方面提供的内容很少。无论如何,重要的一点是,进化论的思想或哲学在整个世纪中都弥漫着空气,并且对社会学作为一门类似于地质学、天文学和生物学等领域的科学的思想做出了深刻的贡献。进化论是一个渗透和令人困惑的观念,就像中世纪欧洲的三位一体一样。达尔文既彻底改变了它,又赋予了它巨大的权威,使进化论与科学并驾齐驱。社会科学家会声称这种权威,尽管他们中很少有人会意识到它所反映的转变。

History of the separate disciplines 独立学科的历史

Among the disciplines that formed the social sciences, two contrary, for a time equally powerful, tendencies at first dominated them. The first was the drive toward unification, toward a single, master social science, whatever it might be called. The second tendency was toward specialization of the individual social sciences. If, clearly, it is the second that has triumphed, with the results to be seen in the disparate, sometimes jealous, highly specialized disciplines seen today, the first was not without great importance and must also be examined.

在构成社会科学的学科中,有两门相反的学科,在一段时间内同样强大,起初的趋势占据了主导地位。首先是走向统一,走向单一的、掌握社会科学的动力,无论它叫什么。第二种趋势是个别社会科学的专业化。如果很明显,第二项取得了胜利,其结果可以在今天看到的不同、有时令人嫉妒、高度专业化的学科中看到,那么第一项并非没有非常重要,也必须加以检验。

What emerges from the critical rationalism of the 18th century is not, in the first instance, a conception of need for a plurality of social sciences, but rather for a single science of humanity that would take its place in the hierarchy of the sciences that included the fields of astronomy, physics, chemistry, and biology. In the 1840s, Comte called for a new science, one with humanity, not humans as animals, as its subject (humans as animals already being a subject of biology). Although he conceived of society as the distinguishing characteristic of humanity, he assuredly had but a single encompassing science in mind—not a congeries of disciplines, each concerned with some single aspect of human behaviour in society. The same was true of Bentham, Marx, and Spencer. All of these thinkers, and there were many others to join them, saw the study of society as a unified enterprise. They would have scoffed, and on occasion did, at any notion of a separate economics, political science, sociology, and so on. Humanity is an indivisible thing, they would have argued; so, too, must be the study of society, its distinguishing characteristic.

从 18 世纪的批判理性主义中得出的,首先并不是需要多种社会科学的概念,而是需要一门单一的人文科学,在包括天文学、物理学、化学和生物学领域的科学等级制度中占有一席之地。在 1840 年代,孔德呼吁一门新的科学,一门以人性而不是作为动物的人类为学科的科学(作为动物的人类已经是生物学的主题)。尽管他认为社会是人类的显著特征,但他心中肯定只有一门包罗万象的科学——而不是一门学科的集合,每个学科都与人类社会行为的某个单一方面有关。边沁、马克思和斯宾塞也是如此。所有这些思想家,以及许多其他加入他们的思想家,都将社会研究视为一项统一的事业。他们会嘲笑,有时也会嘲笑任何独立的经济学、政治学、社会学等概念。他们会争辩说,人性是不可分割的;对社会的研究也必须如此,社会的显著特征。

It was, however, the opposite tendency of specialization or differentiation that won out. No matter how the century began, or what were the dreams of a Comte, Spencer, or Marx, when the 19th century ended, not one but several distinct, competitive social sciences were to be found. Aiding this process was the development of the colleges and universities. The growing desire for an elective system, for a substantial number of academic specializations, and for differentiation of academic degrees contributed strongly to the differentiation of the social sciences. This was first and most strongly to be seen in Germany, where, from about 1815 on, all scholarship and science were based in the universities and where competition for status among the several disciplines was keen. But by the end of the century the same phenomenon of specialization was to be found in the United States (where admiration for the German system was very great in academic circles) and, in somewhat less degree, in France and England. On the face of it, the differentiation of the social sciences in the 19th century was but one aspect of a larger process that was to be seen vividly in the physical sciences and the humanities. No major field escaped the lure of specialization of investigation, and clearly, a great deal of the sheer bulk of learning that passed from the 19th to the 20th century was the direct consequence of this specialization. But the reasons behind specialization in the social sciences, the category that earlier did not exist, were different.

然而,专业化或差异化的相反趋势占了上风。无论这个世纪是如何开始的,也无论孔德、斯宾塞或马克思的梦想是什么,当 19 世纪结束时,人们都会发现不是一个,而是几个截然不同的、有竞争力的社会科学。帮助这一过程的是学院和大学的发展。对选修制度、大量学术专业和学位差异化的日益增长的渴望极大地促进了社会科学的差异化。这在德国最先也是最强烈地出现,从大约 1815 年开始,所有的学术和科学都以大学为基础,几个学科之间对地位的竞争非常激烈。但到本世纪末,同样的专业化现象也出现在美国(学术界对德国制度的钦佩非常大),法国和英国的程度也稍小一些。从表面上看,19 世纪社会科学的分化只是一个更大过程的一个方面,而这一过程在物理科学和人文科学中可以生动地看到。没有一个主要领域能逃脱研究专业化的诱惑,显然,从 19 世纪到 20 世纪的大量学术是这种专业化的直接结果。但是,社会科学专业化背后的原因,这个以前不存在的类别,是不同的。

Economics 经济学

It was economics that first attained the status of an exclusive area of speculation and study among the social sciences. The huge volumes on administration, with their extensive lexicons, written by German cameralists, and that autonomy and self-regulation that the physiocrats and Smith (especially as interpreted by German academics) had found, or thought they had found, in the processes of wealth, in the operation of prices, rents, interest, and wages, during the 18th century became the basis of a separate and distinctive trend of thought, called “political economy,” in the 19th. Hence the emphasis upon what came to be widely called laissez-faire. If, as it was argued, the processes of wealth operate naturally in terms of their own built-in mechanisms, then not only should these be studied separately but they should, in any wise polity, be left alone by government and society. This was, in general, the overriding emphasis of such thinkers as Ricardo, Mill, and Nassau William Senior in England, of Frédéric Bastiat and Say in France, and, somewhat later, the Austrian school of Carl Menger. This emphasis is today called “classical” in economics, and it is even now, though with substantial modifications, a strong position in the field.

正是经济学首先在社会科学中获得了一个专属的投机和研究领域的地位。18 世纪,由德国摄影家撰写的大量行政管理著作及其广泛的词典,以及主学家和斯密(尤其是德国学者的解释)在财富过程中发现的或认为他们已经发现的自主性和自我调节,成为一种独立而独特的思想趋势的基础。 在 19 世纪被称为“政治经济学”。因此,强调后来被广泛称为自由放任的东西。如果像人们所说的那样,财富的过程是按照它们自己的内在机制自然运作的,那么它们不仅应该被单独研究,而且在任何明智的政体中,它们都应该被政府和社会所忽视。总的来说,这是英国的李嘉图、穆勒和老拿骚·威廉、法国的弗雷德里克·巴斯蒂亚和萨伊,以及后来的奥地利学派卡尔·门格尔 (Carl Menger) 等思想家的压倒一切的重点。这种强调在今天被称为经济学中的“古典”,即使经过大量修改,它现在在该领域仍然占据着强势地位。

There were from the beginning, however, thinkers on the subject, including Smith himself, who diverged sharply from this laissez-faire, classical view. In Germany the enormously influential Friedrich List originated the school of “national economy”—which would be today recognized as economic nationalism, opposing international free trade and advocating protectionist measures for domestic economy (a view with which Smith agreed under certain circumstances, the difference between Smith and List being that the former was a pragmatist, while for the latter the position was a matter of principle). There were also the so-called historical economists, proceeding from the presuppositions of social evolution, referred to above. Such figures as Wilhelm Roscher and Karl Knies in Germany tended to dismiss the assumptions of timelessness and universality regarding economic behaviour that were axiomatic among the German followers of Smith, and they strongly insisted upon the developmental character of capitalism, evolving in a long series of stages from other types of economy.

然而,从一开始就有关于这个问题的思想家,包括斯密本人,他们与这种自由放任的古典观点截然不同。在德国,极具影响力的弗里德里希·李斯特(Friedrich List)开创了“国民经济”学派——今天被认为是经济民族主义,反对国际自由贸易并倡导国内经济的保护主义措施(斯密在某些情况下同意这一观点,斯密和李斯特的区别在于前者是实用主义者,而后者的立场是一个原则问题)。还有所谓的历史经济学家,他们从上面提到的社会进化的前提出发。德国的威廉·罗舍尔 (Wilhelm Roscher) 和卡尔·克尼斯 (Karl Knies) 等人物倾向于摒弃在斯密的德国追随者中不言而喻的关于经济行为的永恒性和普遍性的假设,他们强烈坚持资本主义的发展特征,从其他类型的经济中分一系列漫长的阶段演变而来。

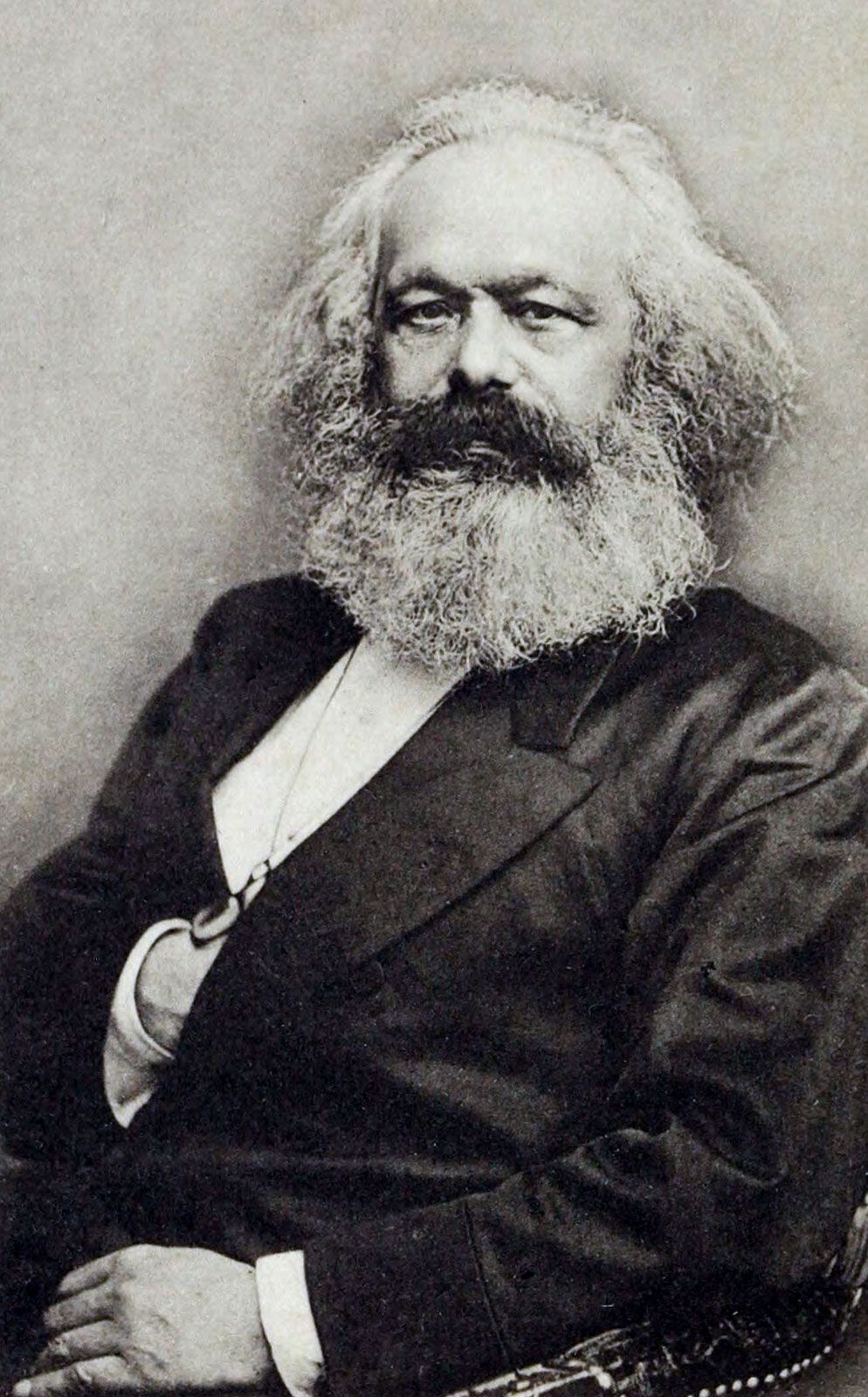

Karl Marx

卡尔·马克思

Also prominent throughout the century were those who came to be called the socialists. They too repudiated any notion of timelessness and universality in capitalism and its elements of private property, competition, and profit. Not only was this system but a passing stage of economic development; it could be—and, as Marx was to emphasize, would be—shortly supplanted by a more humane and also realistic economic system based upon cooperation, the people’s ownership of the means of production, and planning that would eradicate the vices of competition and conflict.

在整个世纪中,那些后来被称为社会主义者的人也非常突出。他们也否定了资本主义及其私有财产、竞争和利润要素中任何永恒和普遍的概念。这个系统不仅是经济发展的过渡阶段;它可能——而且,正如马克思所强调的,将很快被一种更人道、更现实的经济制度所取代,这种经济制度的基础是合作、人民对生产资料的所有权以及消除竞争和冲突弊端的计划。

Political science 政治学

Rivalling economic thought in popularity during the century was “political science,” so called long before “science” was appropriated as the proper name for the unbiased exploration of the empirical world. The line of systematic interest in the state that had begun in modern Europe with Niccolò Machiavelli, Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau, among others, widened and lengthened in the 19th century, the consequence of the two revolutions. If the Industrial Revolution seemed to supply all the problems frustrating the existence of a stable and humane society, the political-democratic revolution could be seen as containing many of the answers to these problems. It was the democratic revolution, especially in France, that created the vision of a political government responsible for all aspects of human society and, most important, possessed the power to wield this responsibility. This power, known as sovereignty, could be seen as holding the same relation to political science in the 19th century that capital held to economic thought. A very large number of political “scientists” essentially ruminated on the varied properties of sovereignty. There was a strong tendency on the part of such thinkers as Bentham, Austin, and Mill in England and Francis Lieber and Woodrow Wilson in the United States to see the state and its claimed sovereignty over human lives in much the same terms in which classical political economists saw capitalism.

在本世纪流行的经济思想中,与“政治学”相媲美的是“政治学”,早在“科学”被用作对实证世界进行公正探索的专有名称之前,它就已经被称为“政治学”。从尼科洛·马基雅维利、霍布斯、洛克和卢梭等人开始于现代欧洲的系统性国家利益线,在 19 世纪扩大了和延长,这是两次革命的结果。如果说工业革命似乎提供了阻碍稳定和人道社会存在的所有问题,那么政治民主革命可以被视为包含了这些问题的许多答案。正是民主革命,尤其是在法国,创造了一个负责人类社会各个方面的政治政府的愿景,最重要的是,它拥有行使这一责任的权力。这种被称为主权的权力可以被视为与 19 世纪的政治学有着相同的关系,就像资本与经济思想的关系一样。非常多的政治“科学家”基本上都在思考主权的各种特性。英国的边沁、奥斯汀和穆勒,以及美国的弗朗西斯·利伯和伍德罗·威尔逊等思想家都强烈倾向于以古典政治经济学家看待资本主义的方式看待国家及其声称的对人类生活的主权。

Among political scientists there was the same historical-evolutionary dissent from this view, however, that existed in political economy. Such writers as Sir Henry Maine in England, Numa Fustel de Coulanges in France, and Otto von Gierke in Germany declared that state and sovereignty were not timeless and universal nor the results of some “social contract” envisaged by such philosophers as Locke and Rousseau but, rather, structures formed slowly through developmental or historical processes. Hence the strong interest, especially in the late 19th century, in the origins of political institutions in kinship, village, and caste, and in the successive stages of development that have characterized these institutions. In political science, as in political economy, in short, the “classical” analytical approach was strongly rivalled by the evolutionary. Both approaches go back to the 18th century in their fundamental elements, but what is seen in the 19th century is the greater systematization and the much wider range of data employed.

然而,在政治学家中,对这种观点存在同样的历史进化论异议,这与政治经济学中存在的相同。英国的亨利·缅因爵士(Sir Henry Maine)、法国的努马·福斯特尔·德·库朗热(Numa Fustel de Coulanges)和德国的奥托·冯·吉尔克(Otto von Gierke)等作家宣称,国家和主权不是永恒的和普遍的,也不是洛克和卢梭等哲学家所设想的某种“社会契约”的结果,而是通过发展或历史过程缓慢形成的结构。因此,特别是在 19 世纪后期,人们对亲属、村庄和种姓政治制度的起源以及这些制度的连续发展阶段产生了浓厚的兴趣。简而言之,在政治学中,就像在政治经济学中一样,“经典”分析方法与进化论有力地竞争。这两种方法的基本要素都可以追溯到 18 世纪,但在 19 世纪可以看到更大的系统化和更广泛的数据使用。

Cultural anthropology 文化人类学

Anthropology also originated in the 19th century. Strictly defined as the science of humankind, it could be seen as superseding specialized areas of focus such as political economy and political science. In practice and from the beginning, however, anthropology concerned itself overwhelmingly with small-scale preindustrial societies. On the one hand was physical anthropology, concerned chiefly with the evolution of humans as a biological species, with the successive forms and protoforms of the species, and with genetic systems. On the other hand was social and cultural anthropology: here the interest was in the full range of humankind’s institutions, though its researches were in fact confined to those found among existing preliterate peoples in Africa, Oceania, Asia, and the Americas. Above all other concepts, “culture” was the central element of this great area of anthropology, or ethnology, as it was often called to distinguish it from physical anthropology. Culture, as a concept, called attention to the nonbiological, nonracial, noninstinctual dimension of human life, the basis of what is called civilization: its values, techniques, and ideas in all spheres. Tylor’s landmark work of 1871, Primitive Culture, defined culture as the part of human behaviour that is learned—an inadequate definition, as proved by the fact that much of animal behaviour is also learned, the difference between animal and human behaviour being, rather, in the character of their respective learning: direct among animals and mostly indirect among humans. Since of all social sciences cultural anthropology places the greatest emphasis on the cultural foundations of human behaviour and thought in society, this inadequate definition has been in no small part responsible for the inadequate understanding of culture in all of them.

人类学也起源于 19 世纪。它被严格定义为人类的科学,可以被视为取代了政治经济学和政治学等专业重点领域。然而,在实践中,从一开始,人类学就压倒性地关注小规模的前工业化社会。一方面是体质人类学,主要关注人类作为生物物种的进化,物种的连续形式和原始形式,以及遗传系统。另一方面是社会和文化人类学:这里的兴趣在于人类的所有制度,尽管它的研究实际上仅限于非洲、大洋洲、亚洲和美洲现有的未识字民族的研究。在所有其他概念中,“文化”是人类学或民族学这一伟大领域的核心要素,因为人们通常这样称呼它以区别于体质人类学。文化作为一个概念,呼吁人们关注人类生活的非生物、非种族、非本能的维度,这是所谓文明的基础:它在各个领域的价值观、技术和思想。泰勒 1871 年的里程碑式著作《原始文化》将文化定义为人类行为中被学习的一部分——这个定义是不充分的,正如动物的大部分行为也是被学习的事实所证明的那样,动物和人类行为之间的区别在于它们各自学习的性质:在动物之间是直接的,在人类之间主要是间接的。由于在所有社会科学中,文化人类学最强调人类行为和社会思想的文化基础,因此这种不适当的定义在很大程度上是导致所有社会科学对文化理解不足的原因。

Scarcely less than political science or political economy, cultural anthropology shared in the themes of the two revolutions and their impact on the world. If the data that cultural anthropologists actually worked with were generally in the remote areas of the world, it was the effects of the two revolutions that, in a sense, kept opening up these parts of the world to their inquiry. And, as was true of the other social sciences, the cultural anthropologists were immersed in economic problems and problems of polity, social class, and community, albeit among preliterate rather than “modern” peoples.

文化人类学几乎不亚于政治学或政治经济学,它与两次革命的主题及其对世界的影响相同。如果说文化人类学家实际研究的数据通常来自世界的偏远地区,那么从某种意义上说,正是两次革命的影响不断为世界这些地区打开了他们的研究空间。而且,与其他社会科学一样,文化人类学家沉浸在经济问题和政体、社会阶层和社区问题中,尽管这些问题是在识字前而不是“现代”民族中。

Overwhelmingly, without major exception indeed, cultural anthropology was evolutionary in thrust in the 19th century. Tylor and Sir John Lubbock in England, Morgan in the United States, Adolf Bastian and Theodor Waitz in Germany, and all others in the main line of the study of “primitive” culture saw existing indigenous societies in the world as prototypes of their own “primitive ancestors”—fossilized remains, so to speak, of stages of development that western Europe had once gone through. Despite the vast array of data compiled on non-Western cultures, the same basic European-centred objectives are to be found among cultural anthropologists as among other social thinkers in the century. Almost universally, then, the modern West was regarded as the latest point in a line of progress that was single and unilinear and on which all other peoples in the world could be fitted as illustrations, as it were, of Western people’s own past.

事实上,绝大多数情况下,文化人类学在 19 世纪是进化论的。英国的泰勒和约翰·拉伯克爵士、美国的摩根、德国的阿道夫·巴斯蒂安和西奥多·怀茨,以及“原始”文化研究主线的所有其他人都将世界上现存的土著社会视为他们自己的“原始祖先”的原型——可以说,是西欧曾经经历过的发展阶段的化石遗骸。尽管汇编了大量关于非西方文化的数据,但在文化人类学家和本世纪的其他社会思想家中可以找到相同的以欧洲为中心的基本目标。因此,现代西方几乎普遍被视为单一和单线进步路线中的最新点,世界上所有其他民族都可以根据它来说明西方人民自己的过去。

Sociology 社会学

Sociology came into being in precisely these terms, and during much of the century it was not easy to distinguish between a great deal of so-called sociology and social or cultural anthropology. Even if almost no sociologists in the century made empirical studies of indigenous peoples, as did the anthropologists, their interest in the origin, development, and probable future of humankind was not less great than what could be found in the writings of the anthropologists. It was Comte who applied to the science of humanity the word sociology, and he used it to refer to what he imagined would be a single, all-encompassing, science that would take its place at the top of the hierarchy of sciences—a hierarchy that Comte saw as including astronomy (the oldest of the sciences historically) at the bottom and with physics, chemistry, and biology rising in that order to sociology, the latest and grandest of the sciences. There was no thought in Comte’s mind—nor was there in the mind of Spencer, whose general view of sociology was very much like Comte’s—of there being other competing social sciences. Sociology would be to the whole of the social, i.e., human, world what each of the other great sciences was to its appropriate sphere of reality.

社会学正是在这些术语中诞生的,在本世纪的大部分时间里,要区分大量的所谓社会学和社会或文化人类学并不容易。即使本世纪几乎没有社会学家像人类学家那样对土著人民进行实证研究,他们对人类起源、发展和可能的未来的兴趣并不亚于人类学家的著作。正是孔德将社会学一词应用于人类科学,他用它来指代他想象中的一门单一的、包罗万象的科学,它将在科学等级制度的顶端占据一席之地——孔德认为这个等级制度包括天文学(历史上最古老的科学)在底部和物理学。 化学和生物学按照这个顺序上升到社会学,这是最新和最伟大的科学。孔德的脑海中没有思想——斯宾塞的脑海中也没有——他对社会学的一般看法与孔德非常相似——还有其他相互竞争的社会科学。社会学之于整个社会,即人类世界,就像其他伟大的科学之于其适当的现实领域一样。

Both Comte and Spencer believed that civilization as a whole was the proper subject of sociology. Their works were concerned, for the most part, with describing the origins and development of civilization and also of each of its major institutions. Both declared sociology’s main divisions to be “statics” and “dynamics,” the former concerned with processes of order in human life (equated with society), the latter with processes of evolutionary change. Both thinkers also saw all existing societies in the world as reflective of the successive stages through which Western society had advanced in time over a period of tens of thousands of years.

孔德和斯宾塞都认为,文明作为一个整体是社会学的适当主题。他们的作品在很大程度上涉及描述文明的起源和发展,以及文明的每个主要机构。两者都宣称社会学的主要分支是“静态”和“动力学”,前者关注人类生活的秩序过程(等同于社会),后者关注进化变化的过程。两位思想家还认为世界上所有现存的社会都反映了西方社会在数万年的时间中发展的连续阶段。

Not all thinkers in the 19th century, who would be considered sociologists today, shared this approach, however. Side by side with the “grand” view represented by Comte and Spencer were those in the century who were primarily interested in the social problems that they saw around them—consequences, as they interpreted them, of the two revolutions, the industrial and democratic. Thus, in France just after mid-century, Le Play published a monumental study of the social aspects of the working classes in Europe, Les Ouvriers européens (1855; “European Workers”), which compared families and communities in all parts of Europe and even other parts of the world. Tocqueville, especially in the second volume of Democracy in America, provided an account of the customs, social structures, and institutions in America, dealing with these—and also with the social and psychological problems of Americans in that day—as aspects of the impact of the democratic and industrial revolutions upon traditional society.

然而,并非所有 19 世纪的思想家(今天被认为是社会学家)都同意这种方法。与孔德和斯宾塞所代表的“宏大”观点并列的是那些本世纪的人,他们主要对他们周围看到的社会问题感兴趣——正如他们所解释的那样,是工业革命和民主革命的后果。因此,在本世纪中叶之后的法国,Le Play 出版了一篇关于欧洲工人阶级社会方面的不朽研究,Les Ouvriers européens(1855 年;“欧洲工人”),该研究比较了欧洲各地甚至世界其他地区的家庭和社区。托克维尔,特别是在《美国的民主》第二卷中,描述了美国的习俗、社会结构和制度,处理了这些问题——以及当时美国人的社会和心理问题——作为民主革命和工业革命对传统社会影响的各个方面。

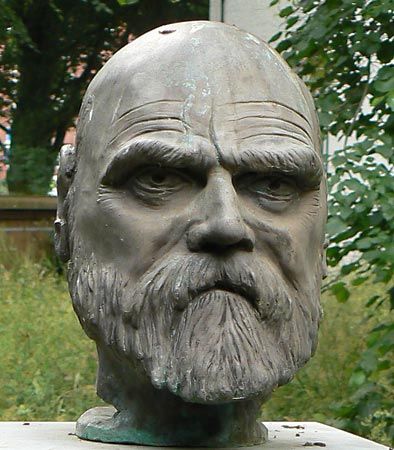

Ferdinand Tönnies, bust in Husum, Germany.

斐迪南·滕尼斯,位于德国胡苏姆的半身像。

斐迪南·滕尼斯(1855—1936)社会学形成时期的著名社会学家,德国的现代社会学的缔造者之一。 他的社会学著作,尤其是成名作《共同体与社会》对社会学界产生了深远的影响。

At the very end of the 19th century, in both France and Germany, there appeared some of the works in sociology that were to prove more influential in their effects upon the actual academic discipline in the 20th century. Tönnies, in his Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft (1887; translated as Community and Society), sought to explain all major social problems in the West as the consequence of the West’s historical transition from the communal, status-based, concentric society of the Middle Ages to the more individualistic, impersonal, and large-scale society of the democratic-industrial period. In general terms, allowing for individual variations of theme, these are considered the views of Weber, Simmel, and Durkheim (all of whom also wrote in the late 19th and early 20th century). These were the figures who, starting from the problems of Western society that could be traced to the effects of the two revolutions, did the most to establish the discipline of sociology as it was practiced for much of the 20th century.

在 19 世纪末,在法国和德国,出现了一些社会学著作,这些著作被证明对 20 世纪实际学术学科的影响更大。Tönnies 在他的 Gemeinschaft und Gesellschaft(1887 年,译为《社区与社会》)中,试图解释西方的所有主要社会问题,这些问题是西方从中世纪的公共、基于地位的、同心的社会向民主工业时期更加个人主义、非个人化和大规模社会的历史转变的结果。一般来说,考虑到主题的个体变化,这些被认为是韦伯、西美尔和涂尔干的观点(他们都在 19 世纪末和 20 世纪初写作)。这些人物从可以追溯到两次革命影响的西方社会问题开始,为建立 20 世纪大部分时间所实践的社会学学科做出了最大的贡献。

Social psychology 社会心理学

Wilhelm Wundt.

威廉·冯特(1832年8月16日—1920年8月31日),德国生理学家、心理学家、哲学家,被公认为是实验心理学之父。他于1879年在莱比锡大学创立世界上第一个专门研究心理学的实验室,这被认为是心理学成为一门独立学科的标志。他学识渊博,著述甚丰,一生作品达540余篇,研究领域涉及哲学、心理学、生理学、物理学、逻辑学、语言学、伦理学、宗教等。

Social psychology as a distinct trend of thought also originated in the 19th century, although its outlines were perhaps somewhat less clear than was true of the other social sciences. The close relation of the human mind to the social order, its dependence upon education and other forms of socialization, was well known in the 18th century. In the 19th century, however, an ever more systematic thinking came into being to uncover the social and cultural roots of human psychology and also the several types of “collective mind” that analysis of different cultures and societies in the world might reveal. In Germany, Moritz Lazarus and Wilhelm Wundt sought to fuse the study of psychological phenomena with analyses of whole cultures. Folk psychology, as it was called, did not, however, last very long.

社会心理学作为一种独特的思潮也起源于 19 世纪,尽管它的轮廓可能比其他社会科学要不清晰。人类思想与社会秩序的密切关系,以及它对教育和其他形式的社会化的依赖,在 18 世纪是众所周知的。然而,在 19 世纪,一种更加系统的思考出现了,以揭示人类心理的社会和文化根源,以及对世界上不同文化和社会的分析可能揭示的几种类型的“集体思想”。在德国,莫里茨·拉撒路 (Moritz Lazarus) 和威廉·温特 (Wilhelm Wundt) 试图将心理现象的研究与对整个文化的分析融合在一起。然而,俗间心理学,正如它的名字一样,并没有持续很长时间。

Much more esteemed were the works of such thinkers as Gabriel Tarde, Gustave Le Bon, Lucien Lévy-Bruhl, and Durkheim in France and Simmel in Germany (all of whom also wrote in the early 20th century). Here, in concrete, often highly empirical studies of small groups, associations, crowds, and other aggregates (rather than in the main line of psychology during the century, which tended to be sheer philosophy at one extreme and a variant of physiology at the other) are to be found the real beginnings of social psychology. Although the point of departure in each of the studies was the nature of association, they dealt, in one degree or another, with the internal processes of psychosocial interaction, the operation of attitudes and judgments, and the social basis of personality and thought—in short, with those phenomena that would, at least in the 20th century, be the substance of social psychology as a formal discipline.

更受尊敬的是法国的加布里埃尔·塔尔德 (Gabriel Tarde)、古斯塔夫·勒庞 (Gustave Le Bon)、吕西安·莱维-布鲁尔 (Lucien Lévy-Bruhl) 和涂尔干 (Durkheim) 和德国的西梅尔 (Simmel) 等思想家的著作(他们都在 20 世纪初写作)。在这里,在对小团体、协会、人群和其他聚合体(而不是在本世纪心理学的主线中,在一个极端往往是纯粹的哲学,另一个极端往往是生理学的变体)的具体、通常是高度实证的研究中,可以找到社会心理学的真正开端。尽管每项研究的出发点都是联想的性质,但它们或多或少地涉及社会心理互动的内部过程、态度和判断的运作以及人格和思想的社会基础——简而言之,至少在 20 世纪,这些现象会 成为社会心理学作为一门正式学科的实质。

Social statistics and social geography 社会统计和社会地理学

Two final 19th-century trends to become integrated into the social sciences in the 20th century are social statistics and social (or human) geography. At that time, neither achieved the notability and acceptance in colleges and universities that such fields as political science and economics did. Both, however, were as clearly visible by the latter part of the century and both were to exert a great deal of influence on the other social sciences by the beginning of the 20th century: social statistics on sociology and social psychology preeminently; social geography on political science, economics, history, and certain areas of anthropology, especially those areas dealing with the dispersion of races and the diffusion of cultural elements. In social statistics the key figure of the century was Quetelet, who was the first, on any systematic basis, to call attention to the kinds of structured behaviour that could be observed and identified only through statistical means. It was he who brought into prominence the momentous concept of “the average man” and his behaviour. The two major figures in social or human geography in the century were Friedrich Ratzel in Germany and Paul Vidal de La Blache in France. Both broke completely with the crude environmentalism of earlier centuries, which had sought to show how topography and climate actually determine human behaviour, and they substituted the more subtle and sophisticated insights into the relationships of land, sea, and climate on the one hand and, on the other, the varied types of culture and human association that are to be found on Earth.

19 世纪最后两个被纳入 20 世纪社会科学的趋势是社会统计学和社会(或人文)地理学。当时,两者都没有在高等院校中取得像政治学和经济学等领域那样的知名度和接受度。然而,这两者都在本世纪下半叶清晰可见,并且到 20 世纪初,两者都对其他社会科学产生了巨大影响:社会学和社会心理学的社会统计学占主导地位;社会地理学 关于政治学、经济学、历史和人类学的某些领域,特别是那些涉及种族分散和文化元素扩散的领域。在社会统计学方面,本世纪的关键人物是奎特莱特,他是第一个在任何系统的基础上,引起人们对只有通过统计手段才能观察到和识别的结构化行为类型的人们的关注。正是他使“普通人”这一重要概念和他的行为变得突出。本世纪社会或人文地理学领域的两位主要人物是德国的弗里德里希·拉策尔 (Friedrich Ratzel) 和法国的保罗·维达尔·德拉布拉什 (Paul Vidal de La Blache)。两者都与前几个世纪粗暴的环保主义完全决裂,后者试图展示地形和气候如何实际决定人类行为,他们一方面取代了对陆地、海洋和气候关系的更微妙和复杂的见解,另一方面,他们取代了地球上各种类型的文化和人类交往。

Robert A. NisbetLiah Greenfeld

Social science from the turn of the 20th century 20 世纪之交的社会科学

Science and social science 科学和社会科学

It is impossible to understand, much less to assess, the social sciences without first understanding what, in general, science is. The word itself conveys little. As late as the 18th century, science was used as a near-synonym of art, both meaning any kind of knowledge—though the sciences and the arts could perhaps be distinguished by the former’s greater abstraction from reality. Art in this sense designated practical knowledge of how to do something—as in the “art of love” or the “art of politics”—and science meant theoretical knowledge of that same thing—as in the “science of love” or the “science of politics.” But, after the rise of modern physics in the 17th century, particularly in the English-speaking world, the connotation of science changed drastically. Today, occupying on the knowledge continuum the pole opposite that of art (which is conceived as subjective, living in worlds of its own creation), science, considered as a body of knowledge of the empirical world (which it accurately reflects), is generally understood to be uniquely reliable, objective, and authoritative. The change in the meaning of the term reflected the emergence of science as a new social institution—i.e., an established way of thinking and acting in a particular sphere of life—that was organized in such a way that it could consistently produce this type of knowledge.

如果不首先了解科学通常是什么,就不可能理解社会科学,更不可能评估社会科学。这个词本身传达的意义不大。直到 18 世纪,科学几乎被用作艺术的同义词,两者都意味着任何类型的知识——尽管科学和艺术可能可以通过前者与现实的更大抽象来区分。在这个意义上,艺术是指关于如何做某事的实践知识——如“爱的艺术”或“政治的艺术”——而科学是指关于同一事物的理论知识——如“爱的科学”或“政治的科学”。但是,在 17 世纪现代物理学兴起之后,特别是在英语世界,科学的内涵发生了翻天覆地的变化。今天,在知识连续体上占据与艺术相反的一极(艺术被认为是主观的,生活在自己创造的世界中),科学被认为是经验世界的知识体系(它准确地反映了这一点),通常被理解为独特可靠、客观和权威。该术语含义的变化反映了科学作为一种新的社会制度的出现——即在特定生活领域中一种既定的思维和行为方式——它的组织方式使其能够始终如一地产生这种类型的知识。

Also called “modern science”—to distinguish it from sporadic attempts to produce objective knowledge of empirical reality in the past—the institution of science is oriented toward the understanding of empirical reality. That institution presupposes not only that the world of experience is ordered and that its order is knowable but also that the order is worth understanding in its own right. When, as in the European Middle Ages, God was conceived as the only reality worth knowing, there was no place for a consistent effort to understand the empirical world. The emergence of the institution of science, therefore, was predicated on the reevaluation of the mundane vis-à-vis the transcendental. In England the perceived importance of the empirical world rose tremendously with the replacement of the religious consciousness of the feudal society of orders by an essentially secular national consciousness following the 15th-century Wars of the Roses (see below Applications of the science of humanity: nationalism, economic growth, and mental illness). Within a century of redefining itself as a nation, England placed the combined forces of royal patronage and social prestige behind the systematic investigation of empirical reality, thereby making the institution of science a magnet for intellectual talent.

科学机构也被称为“现代科学”——为了区别于过去零星地试图产生对经验现实的客观知识——科学机构以理解经验现实为导向。这个机构不仅假定经验世界是有序的,而且它的秩序是可知的,而且这种秩序本身就值得理解。当像欧洲中世纪一样,上帝被认为是唯一值得了解的现实时,就没有地方持续努力来理解经验世界。因此,科学机构的出现是建立在对世俗与超验的重新评估之上的。在15世纪的玫瑰战争之后,随着封建秩序社会的宗教意识被本质上世俗的民族意识所取代,实证世界的重要性大大上升(见下文人文科学的应用:民族主义、经济增长和精神疾病)。在重新定义自己作为一个国家的一个世纪内,英格兰将皇室赞助和社会声望的联合力量置于对实证现实的系统调查背后,从而使科学机构成为吸引知识人才的磁铁。

The goal of understanding the empirical world as it is prescribed a method for its gradual achievement. Eventually called the method of conjecture and refutation, or the scientific method (see hypothetico-deductive method), it consisted of the development of hypotheses, formulated logically to allow for their refutation by empirical evidence, and the attempt to find such evidence. The scientific method became the foundation of the normative structure of science. Its systematic application made for the constant supersession of contradicted and refuted hypotheses by better ones—whose sphere of consistency with the evidence (their truth content) was accordingly greater—and for the production of knowledge that was ever deeper and more reliable. In contrast to all other areas of intellectual endeavour (and despite occasional deviations) scientific knowledge has exhibited sustained growth. Progress of that kind is not simply a desideratum: it is an actual—and distinguishing—characteristic of science.

理解经验世界的目标规定了逐步实现的方法。最终被称为猜想和反驳的方法,或科学方法(见假设-演绎法),它包括假设的发展,逻辑地表述以允许通过经验证据反驳它们,并试图找到这些证据。科学方法成为科学规范结构的基础。它的系统应用使得相互矛盾和反驳的假设不断被更好的假设所取代——这些假设与证据的一致性范围(它们的真理内容)相应地更大——并且产生了越来越深入和可靠的知识。与所有其他智力努力领域相反(尽管偶尔会出现偏差),科学知识表现出持续增长。这种进步不仅仅是一种观点:它是科学的一个实际的、独特的特征。

There was no progressive development of objective knowledge of empirical reality before the 17th century—no science, in other words. In fact, there was no development of knowledge at all. Interest in questions that, after the 17th century, would be addressed by science (questions about why or how something is) was individual and passing, and answers to such questions took the form of speculations that corresponded to existing beliefs about reality rather than to empirical evidence. The formation of the institution of science, with its socially approved goal of systematic understanding of the empirical world, as well as its norms of conjecture and refutation, was the first, necessary, condition for the progressive accumulation of objective and reliable knowledge of empirical reality.

在 17 世纪之前,没有经验现实的客观知识的进步发展——换句话说,没有科学。事实上,根本没有知识的发展。对 17 世纪之后由科学解决的问题(关于事物为什么或如何存在的问题)的兴趣是个人的和传递的,对这些问题的回答采取了与关于现实的现有信念相对应的猜测形式,而不是与经验证据相对应的。科学机构的形成,其社会认可的对经验世界的系统理解的目标,以及它的猜想和反驳的规范,是逐步积累关于经验现实的客观和可靠知识的第一个必要条件。

For the science of matter, physics, the institutionalization of science was also a sufficient condition. But the development of sciences of other aspects of reality—specifically of life and of humanity—was prevented for several more centuries by a philosophical belief, dominant in the West since the 5th century bce, that reality has a dual nature, consisting partly of matter and partly of spirit (see also mind-body dualism; spiritualism). The mental or spiritual dimension of reality, which for most of this long period was by far the more important, was empirically inaccessible. Accordingly, the emergence of modern physics in the 17th century led to the identification of the material with the empirical, the scientific, and later with the objective and the real. And this identification in turn caused anything nonmaterial to be perceived as ideal (see idealism), outside the scope of scientific inquiry, subjective, and, eventually, altogether unreal.

对于物质科学、物理学来说,科学的制度化也是一个充分的条件。但是,现实其他方面的科学发展——特别是生命和人类的科学——被一种哲学信仰阻止了几个世纪,这种哲学信仰自公元前 5 世纪以来在西方占主导地位,即现实具有双重性质,部分由物质和部分精神组成(另见身心二元论;唯灵论)。现实的精神或精神层面,在这段漫长时期的大部分时间里是最重要的,但从经验上来说是无法接近的。因此,17 世纪现代物理学的出现导致材料与经验、科学以及后来的客观和现实相认同。而这种认同反过来又导致任何非物质的东西被认为是理想的(参见唯心主义),在科学探究的范围之外,是主观的,最终,完全是不真实的。