注:机翻,未校。

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz: How the ‘I Ching’ Inspired His Binary System

The 5,000-year-old text struck a chord.

这段 5000 年前的文字引起了人们的共鸣。

by Mary von Aue

July 2, 2018

Wikimedia / Ad Meskens

While Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz’s work has influenced centuries of technological innovation, his own influences included Chinese philosophy and divination manuals recorded as early as 1000 BC.

尽管戈特弗里德・威廉・莱布尼茨的工作影响了数世纪的科技创新,但他的灵感来源包括中国哲学以及早在公元前 1000 年就已记录的占卜手册。

The 17th-century philosopher and mathematician developed the binary number system that is still being used today, but his approach to writing in binary code made direct references to the hexagrams and cosmological ideas found in the 9th-century manual, the I Ching.

这位 17 世纪的哲学家和数学家发展了至今仍在使用的二进制数字系统,但他在编写二进制代码时的方式直接引用了 9 世纪占卜手册《易经》中的卦象和宇宙论思想。

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Google Doodle

戈特弗里德·威廉·莱布尼茨 Google 涂鸦

Leibniz’s philosophical texts focused on rationalist thought but also considered matters of faith, as was common among 17th-century philosophers. He’s considered one of the first Western intellectuals to adopt ideas from traditional Chinese philosophies, thanks in part to his personal friendships with Christian missionaries in China. He published his own interpretations of Neo-Confucianism, concluding that Europe would do well to adopt a Confucian ethical tradition. Later historians would link Leibniz’s Monadologie, — his best-known work and theory that the universe is made of an infinite number of simple substances — to early Confucian thought.

莱布尼茨的哲学著作专注于理性主义思想,同时也考虑信仰问题,这在 17 世纪的哲学家中很常见。他被视为第一批采纳传统中国哲学思想的西方知识分子之一,这在一定程度上得益于他与在中国的基督教传教士的个人友谊。他发表了自己对新儒学的解读,认为欧洲应该采纳儒家的伦理传统。后来的历史学家将莱布尼茨的《单子论》—— 他最著名的作品,提出宇宙由无数简单物质构成的理论 —— 与早期儒家思想联系起来。

However, Leibniz’s research of Eastern philosophy extended to earlier periods of thought, and he wrote extensively about the 9th-century divination manual, the I Ching. The manual, attributed to Fu Xi, was first assembled during China’s Western Zhou period and offered both cosmological maps and philosophical ideas. Leibniz wrote about his own fascination with the manual and noted that the text’s hexagrams corresponded with the binary numbers from 000000 to 111111, arguing that the authors were much more advanced in mathematics than Leibniz’s contemporaries believed.

然而,莱布尼茨对东方哲学的研究延伸到了更早的思想时期,他撰写了大量关于 9 世纪占卜手册《易经》的文章。该手册归功于伏羲,在中国西周时期首次编纂,提供了宇宙学地图和哲学思想。莱布尼茨写到自己对该手册的着迷,并指出著作中的卦象与二进制数字从 000000 到 111111 相对应,认为其作者在数学方面远比莱布尼茨的同时代人所认为的要先进得多。

In one such text, succinctly titled “Explanation of the binary arithmetic, which uses only the characters 1 and 0, with some remarks on its usefulness, and on the light it throws on the ancient Chinese figures of Fu Xi,” Leibniz looks at the binary code of I Ching, represented as Yin and Yang. He argued that all matter can be represented in binary sequencing as ones and zeros, or, as it was expressed in ancient literature, Yin and Yang, which he identifies as terms that represent polar abstract concepts.

在一篇简洁标题为 “二进制算术的解释,该算术仅使用字符 1 和 0,并附带一些关于其有用性的备注,以及它对古代中国伏羲图的启示” 的著作中,莱布尼茨探讨了《易经》的二进制代码,以阴和阳表示。他认为所有物质都可以用二进制序列,即 1 和 0 来表示,或者用古代文献中的表达方式 —— 阴和阳,这两个词被他认定为代表极性抽象概念的术语。

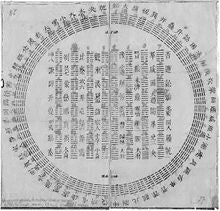

A diagram of I Ching hexagrams with Leibniz’s notations

用莱布尼茨符号表示的《易经》六十四卦图示

Using Leibniz’s rationale, the I Ching uses a complex binary code in its formation of hexagrams. Yin is notated as a broken line while Yang is notated as an unbroken line. These lines are then used in a set of three to form eight trigraphs, which combine to create 64 hexagrams, or forms of larger matter.

根据莱布尼茨的理论,《易经》在其六十四卦的形成中使用了复杂的二进制代码。阴用断线表示,而阳则用不断线表示。这些线条以三条为一组,形成八个三元组,这些三元组结合在一起生成 64 个卦象,或称更大物质的形式。

By seeing binary representation in ancient texts, Leibniz was compelled to continue his own writing of binary systems. This, in turn, became the language of modern computing still being used today, thus linking a 5,000-year-old text to the formation of the digital age.

通过在古代著作中看到二进制表示,莱布尼茨受到启发,继续他自己关于二进制系统的写作。这反过来成为了现代计算机使用的语言,从而将一部 5000 年前的著作与数字时代的形成联系在一起。

~

Leibniz on Number Systems 莱布尼茨谈数字系统

-

Living reference work entry

-

First Online: 25 May 2023

pp 1–31 -

Cite this living reference work entry

Handbook of the History and Philosophy of Mathematical Practice

This chapter examines the pioneering work of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) on various number systems, in particular binary, which he independently invented in the mid-to-late 1670s, and hexadecimal, which he invented in 1679. The chapter begins with the oft-debated question of who may have influenced Leibniz’s invention of binary, though as none of the proposed candidates is plausible, I suggest a different hypothesis that Leibniz initially developed binary notation as a tool to assist his investigations in mathematical problems that were exercising him at the time, namely those concerning the divisibility of composite numbers, primality, and perfect numbers. The chapter then explores Leibniz’s development of binary, his little-known work on binary fractions and expansions, his use of binary as a symbol for creation in his philosophical-theology, and his response to the suggestion that there was a correlation between binary numeration and the hexagrams of the ancient Chinese divinatory text, the Yijing. The chapter then focuses on Leibniz’s work on other number systems, in particular his invention and exploration of hexadecimal as well as his work on duodecimal. The chapter concludes by revealing a hitherto unknown practical application of binary that Leibniz devised in the last year of his life.

本章研究了戈特弗里德·威廉·莱布尼茨(Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz,1646-1716 年)在各种数字系统方面的开创性工作,特别是他在 1670 年代中后期独立发明的二进制和他在 1679 年发明的十六进制。本章以谁可能影响了莱布尼茨发明二进制的经常争论的问题开始,尽管由于所提出的候选人都不可信,我提出了一个不同的假设,即莱布尼茨最初开发了二进制符号作为一种工具,以帮助他研究当时困扰他的数学问题,即那些关于合数整除性的问题。 原初数和完美数。然后,本章探讨了莱布尼茨对二进制的发展,他在二进制分数和扩展方面鲜为人知的工作,他在哲学神学中使用二进制作为创造的符号,以及他对二进制计数与中国古代占卜文本《易经》的卦之间存在相关性的说法的回应。然后,本章重点介绍了莱布尼茨在其他数字系统方面的工作,特别是他对十六进制的发明和探索以及他在十二进制方面的工作。本章的结尾揭示了莱布尼茨在他生命的最后一年设计的一个迄今为止未知的二进制实际应用。

Notes 笔记

1.See Couturat (1901, 473); Zacher (1973, 9–33); Tropfke (1980, 12); and Ingaliso (2017, 111–112).

参见 Couturat (1901,473);Zacher (1973,9-33);Tropfke (1980,12);和 Ingaliso (2017,111-112)。

2.In 1711, decades after devising binary and only 5 years before his death, Leibniz (1768, V: 418) wrote: “Regarding Caramuel’s Mathesis biceps [Old] and New, for which he asks ten thalers, I am unable to judge well because I have not yet seen it, and I fear it may contain vain subtleties, which is not unusual for Caramuel.”

在 1711 年,在发明二进制几十年后,仅在其去世前五年,莱布尼茨写道:“关于卡拉缪尔的《双倍数学》[旧版] 和新版,他索要十塔勒,我无法很好地判断,因为我还没有看到它,我担心它可能包含空洞的诡辩,这对卡拉缪尔来说并不罕见。”

3.This work yielded his first publication in mathematics in February 1678, namely, the short journal article “A new observation about the way of testing whether a number is prime”; see Leibniz 1678. For details of Leibniz’s work on primes, see Mahnke (1912–1913).

这项工作于 1678 年 2 月发表了他在数学领域的第一篇出版物,即一篇简短的期刊文章“关于测试数字是否为素数的方法的新观察”;参见莱布尼茨 1678。有关莱布尼茨关于素数的工作的详细信息,请参见 Mahnke (1912–1913)。

4.In the manuscript entitled “Formarum reductio ad simplices,” written 12 September 1680: “Therefore, 2z–1 – 1 will be divisible by z, if z is prime” (LH 35, 3 A 4 Bl. 14r). During these investigations, Leibniz also glimpsed Wilson’s theorem: (n – 2)! ≡ 1 (mod n), or in Leibniz’s words: “The product of continuous [integers] up to the number which anteprecedes the given integer, when divided by the given integer, leaves 1, if the given integer is prime. If the given integer is derivative, it will leave a number which, since it has a common measure with the given integer, is greater than one” (LH 35 3 B 11 Bl. 21r). However, when testing his articulation of the theorem, Leibniz made a miscalculation that led him to add the false statement “(or the complement of 1)” after “leaves 1.”

在 1680 年 9 月 12 日写的题为“Formarum reductio ad simplices”的手稿中:“因此,如果 z 是素数,那么 2z-1-1 将能被 z 整除”(LH 35,3 A 4 Bl. 14r)。在这些研究中,莱布尼茨还瞥见了威尔逊定理:(n – 2)!≡ 1 (mod n),或者用莱布尼茨的话来说:“连续 [整数] 的乘积直到给定整数前面的数字,当除以给定整数时,如果给定整数是素数,则留下 1。如果给定的整数是导数,它将留下一个数字,因为它与给定的整数有共同的度量,所以大于 1“(LH 35 3 B 11 Bl. 21r)。然而,在测试他对定理的表达时,莱布尼茨犯了一个错误的计算,导致他在“leaves 1”之后添加了错误的陈述“(或 1 的补语)”。

5.In a slightly later manuscript, from 1679 (LH 35, 8, 30 Bl. 148), Leibniz again uses binary notation to illustrate his (still immature) formulation of a prime number theorem, namely, 2 n – 1 2n – 1 2n–1: “Let A = 111111 A = 111111 A=111111, B = 1111 B = 1111 B=1111, C = 111 C = 111 C=111, D = 11 D = 11 D=11. E = A F E = AF E=AF, F = A G F = AG F=AG. Now A A A and B B B are prime among themselves, because their exponents are such, that is, their indices, or the numbers 2 and 3. Therefore A A A and B B B are not prime among themselves and necessarily will become A = A H A = AH A=AH and B = A I B = AI B=AI, and will become J = A K J = AK J=AK. Z z – 1 Zz – 1 Zz–1 is divisible by Z Z Z if Z Z Z is prime, and I have demonstrated this as follows: 22 – 1 22 – 1 22–1 by 3 and 24 – 1 24 – 1 24–1 by 5, therefore 1111 is divisible by 5 and 11 by 3 and 111111 by 7. But 11111 cannot be divided by 6, for since 11 can be divided by 3, 11111 and 11 have a common divisor, yet they are prime among themselves. And hence we have the sought-for demonstration of a reciprocal property of a prime number.”

在 1679 年的一份稍晚的手稿(LH 35, 8, 30 Bl. 148)中,莱布尼茨再次使用二进制记数法来说明他(仍不成熟的)素数定理的公式,即 2 n − 1 2n - 1 2n−1:“设 A = 111111 A = 111111 A=111111, B = 1111 B = 1111 B=1111, C = 111 C = 111 C=111, D = 11 D = 11 D=11。 E = A F E = A F E=AF, F = A G F = A G F=AG。现在 A A A和 B B B彼此互素,因为它们的指数是这样的,即它们的指标,或者说是数字 2 和 3。因此 A A A 和 B B B 并非彼此互素,必然会变成 A = A H A = A H A=AH 和 B = A I B = A I B=AI,并且会变成 J = A K J = A K J=AK。如果 Z Z Z是素数,那么 Z z − 1 Z z - 1 Zz−1 能被 Z Z Z整除,我如下证明这一点: 22 − 1 22 - 1 22−1能被 3 整除, 24 − 1 24 - 1 24−1能被 5 整除,所以 1111 能被 5 整除,11 能被 3 整除,111111 能被 7 整除。但是 11111 不能被 6 整除,因为既然 11 能被 3 整除,11111 和 11 有一个公因数,但它们彼此互素。因此,我们有了所寻求的素数的互反性质的证明。”

6.Euclid, Elements, IX.36. That is, if p p p is a positive integer and 2 p – 1 2p – 1 2p–1 is prime, then 2 p − 1 ( 2 p − 1 ) 2p-1 (2p − 1) 2p−1(2p−1) is perfect.

欧几里得,《元素》,IX.36。也就是说,如果 p p p 是正整数, 2 p – 1 2p – 1 2p–1 是素数,则 2 p − 1 ( 2 p − 1 ) 2p-1 (2p − 1) 2p−1(2p−1) 是完美的。

- Perhaps because of this, in another manuscript on the subject, probably written in 1678, Leibniz sought to demonstrate perfect numbers using a mixture of binary numeration and algebra based thereon (so unrelated to Pauli’s algebra), eventually reaching the conclusion “if 2 z + 1 – 1 2z+1 – 1 2z+1–1 is prime, then 2 2 z + 1 – 2 z 2^{2z+1} – 2^z 22z+1–2z will be a perfect number. Likewise, if z z z is prime, 2 z – 1 – 1 2^{z–1} – 1 2z–1–1 will be divisible by z z z” (LH 35, 3 B 17 Bl. 1).

也许正因为如此,在另一篇可能写于 1678 年的关于该主题的手稿中,莱布尼茨试图使用二进制计数和基于此的代数的混合来证明完美数(与泡利代数无关),最终得出结论“如果 2 z + 1 – 1 2z+1 – 1 2z+1–1 是素数,则 2 2 z + 1 – 2 z 2^{2z+1} – 2^z 22z+1–2z 将是一个完美数。同样,如果 z z z 是素数, 2 z – 1 – 1 2^{z–1} – 1 2z–1–1 将能被 z z z 整除“(LH 35,3 B 17 Bl. 1)。

8.Leibniz explicitly acknowledged these features, at least in the 1680s onward. For example: “The very last digits of a number of the double geometric progression can be easily obtained like this: if 1 is subtracted from it, then it is written in binary: etc.1111111, that is, 1 + 2 + 4 + 8 + 16 + 32 1 + 2 + 4 + 8 + 16 + 32 1+2+4+8+16+32 etc.” (LH 35, 3 B 11 Bl. 10r; cf. LH 35, 8, 30 Bl. 75; LH 35, 13, 3 Bl. 33; LH 35, 15, 5 Bl. 10r; and LH 35, 3 B 5 Bl. 51r).

莱布尼茨明确承认这些特征,至少在 1680 年代以后是这样。例如:“一个双几何级数的最后几位数字可以很容易地得到,就像这样:如果从中减去 1,那么它就用二进制写成:etc.1111111,即 1 + 2 + 4 + 8 + 16 + 32 1 + 2 + 4 + 8 + 16 + 32 1+2+4+8+16+32 等。(LH 35,3 B 11 Bl. 10r;参见 LH 35,8,30 Bl. 75;LH 35,13,3 Bl. 33;LH 35,15,5 Bl. 10r;和 LH 35,3 B 5 Bl. 51r)。

9.A similar table is found in other manuscripts, such as LH 35, 4, 11 Bl. 10r, though this was likely written in 1681.

在其他手稿中也可以找到类似的表格,例如 LH 35,4,11 Bl. 10r,尽管这可能是在 1681 年写成的。

10.Another writing in this vein is printed in Strickland and Lewis (2022, 41–43).

另一篇这方面的著作印在 Strickland 和 Lewis (2022,41-43) 中。

11.Leibniz did not affix a date to them, and the paper contains no watermarks that could be used to determine a dating, so they have to be dated using internal evidence.

莱布尼茨没有为它们贴上日期,而且论文中没有可用于确定日期的水印,因此必须使用内部证据来确定它们的日期。

12.Leibniz also refers to “the binary progression, where only ones and 0 express a number,” in a manuscript on the construction of a universal language, tentatively dated to February 1678 (A VI 4, 68).

莱布尼茨在一份关于构建通用语言的手稿中还提到了“二进制级数,其中只有 1 和 0 表示数字”,暂定日期为 1678 年 2 月(A VI 4,68)。

13.A third is outlined in Strickland and Lewis (2022, 40n2).

Strickland 和 Lewis (2022,40n2) 概述了第三个。

14.Although in one early writing he exclaims that binary will be “remarkable for periodic progressions in expressible quantities which are not whole or rational” (Strickland and Lewis 2022, 32).

尽管在一篇早期的文章中,他惊呼二元将“对于非整体或理性的可表达量的周期性进展来说是非凡的”(斯特里克兰和刘易斯 2022,32)。

15.For further details of Leibniz’s work on the binary expression of his circle formula, see Strickland (2023a).

有关莱布尼茨在圆公式的二进制表达式方面的工作的更多详细信息,请参见 Strickland (2023a)。

16.Also: “Without doubt boundaries or limits are of the essence of creatures, but limits are something privative and consist in the denial of further progress.” Leibniz (2006, 38), cf. A I 15, 369; Leibniz (2006, 102–103); and Strickland (2014, 22).

“此外:”毫无疑问,界限或限制是生物的本质,但限制是私有的,包括对进一步进步的否认。莱布尼茨 (2006,38),参见 A I 15,369;莱布尼茨 (2006,102–103);和斯特里克兰 (2014,22)。

17.Or as he puts it in a manuscript written perhaps in 1695 or possibly in 1702, “things are educed from God’s active power—as Julius Scaliger said—rather than from passive nothing. My invention of the composition of numbers from 0 and 1 would wonderfully support this doctrine” (LH 4, 3, 5e Bl. 5). See Scaliger (1557, fols. 16–17).

或者正如他在可能写于 1695 年或 1702 年的手稿中所说的那样,“事物是从上帝的主动力量中教育的——正如朱利叶斯·斯卡利格 (Julius Scaliger) 所说——而不是从被动的虚无中。我发明的 0 和 1 的数字组合将很好地支持这一学说“(LH 4,3,5e Bl. 5)。参见 Scaliger (1557,fols. 16-17)。

18.When Leibniz did come to write the Theodicy more than a decade later, the binary-creation analogy was not mentioned. The Theodicy was published in 1710. See Leibniz (1985).

十多年后,当莱布尼茨确实来写《神论》时,二元创造的类比并没有被提及。《神论》于 1710 年出版。请参阅Leibniz (1985)。

19.There are other sequences of hexagrams apart from the two mentioned already, such as the Eight Palaces sequence, which predates the Fuxi sequence. These sequences have elicited many studies of their structure, interrelation, and history, though such matters are outside of the scope of this chapter.

除了已经提到的两个卦序列之外,还有其他的卦序列,例如八宫序列,它早于伏羲序列。这些序列引发了对它们的结构、相互关系和历史的许多研究,尽管这些问题超出了本章的范围。

20.For more information on Bouvet’s hypothesis and Leibniz’s reaction thereto, see Kempe (2022, 141–174).

有关布韦假说和莱布尼茨对此的反应的更多信息,请参阅 Kempe (2022,141–174)。

21.For more information about the history of base 16, and Leibniz’s place therein, see Strickland and Jones (2023).

有关 16 进制的历史以及莱布尼茨在其中的地位的更多信息,请参阅 Strickland 和 Jones (2023)。

22.The same conversion of 100000 to 186u016 is also found in a contemporaneous text: LH 35, 8, 30 Bl. 148r.

100000 到 186u016 的相同转换也出现在同时代的文本中:LH 35,8,30 Bl. 148r。

23.Leibniz is probably thinking of Schwenter’s Deliciae physico-mathematicae [The Charms of Physico-Mathematics] of 1636, which was posthumously revised and expanded by Georg Philipp Harsdörffer (1607–1658) in 1651 and again in 1653. However, as far as I have been able to tell, in none of those works is there any mention of duodecimal, let alone any report of anyone endorsing it.

莱布尼茨可能想到了 1636 年施文特的 Deliciae physico-mathematicae [物理数学的魅力],该书在 1651 年和 1653 年由乔治·菲利普·哈斯多夫(Georg Philipp Harsdörffer,1607-1658 年)在他去世后进行了修订和扩展。然而,据我所知,在这些作品中都没有提到 duodecimal,更不用说任何关于任何人认可它的报告了。

24.Leibniz actually wrote “1728,” but this is clearly a mistake as his example uses 1712.

莱布尼茨实际上写了“1728”,但这显然是一个错误,因为他的例子使用了 1712 年。

25.After this example, Leibniz turned to the quaternary system, efficiently sketching out the steps required to convert the decimal value 1712 to 1223004 (LBr 705 Bl. 93r). He then did the same with binary, before turning to the periodicity of columns in binary.

在这个例子之后,莱布尼茨转向四元系统,有效地勾勒出将十进制值 1712 转换为 1223004 (LBr 705 Bl. 93r) 所需的步骤。然后,他对 binary 执行相同的操作,然后转向 binary 中列的周期性。

26.For further details of Leibniz’s tactile binary clock, and an English translation of the manuscript, see Strickland (2023b).

有关莱布尼茨的触觉二进制时钟的更多详细信息,以及手稿的英文翻译,请参见 Strickland (2023b)。

27.Leibniz himself had devised a spring-driven pocket watch in the mid-1670s and continued to improve it even four decades later; see Leibniz 1675, and LH 38 Bl. 274–275.

莱布尼茨本人在 1670 年代中期设计了一款弹簧驱动怀表,并在四十年后继续改进它;参见莱布尼茨 1675 年和 LH 38 Bl. 274-275。

Bibliography

-

Bacon F (1623) De dignitate et augmentis scientiarum, libri IX. Haviland, London

-

Caramuel y Lobkowitz, Juan (1670) Mathesis biceps, vetus et nova. Annison, Campagna

-

Couturat L (1901) La logique de Leibniz. Félix Alcan, Paris

-

Dangicourt P (1710) De periodis columnarum in serie numerorum progressionis arithmeticae dyadice expressorum. Miscellanea Berolinensia 1:336–376

-

Glaser A (1981) History of binary and other nondecimal numeration, 2nd edn. Tomash, Los Angeles

-

Harsdörffer GP (1651) Delitiae mathematicae et physicae der Mathematischen und Philosophischen Erquickstunden. Zweiter Theil. Dümler, Nuremberg

-

Harsdörffer GP (1653) Delitiae mathematicae et physicae der Mathematischen und Philosophischen Erquickstunden. Dritter Theil. Endters, Nuremberg

-

Hill TW (1860) Selections from the papers of the Late Thomas Wright Hill, Esq. F.R.A.S. John W. Parker and Son, London

-

Hochstetter E (1966) Herrn von Leibniz’ Rechnung mit Null und Eins. Siemens, Berlin

-

Ineichen R (2008) Leibniz, Caramuel, Harriot und das Dualsystem. Mitteilungen der deutschen Mathematiker-Vereinigung 16(1):12–15

-

Ingaliso L (2017) Leibniz e la lettura binaria dell’I Ching. In: Lio GMS, Ingaliso L (eds) Alterità e Cosmopolitismo nel Pensiero Moderno e Contemporaneo. Rubbettino, Soveria Mannelli, pp 109–132

-

Intorcetta, Prospero, ChristianWolfgang Herdtrick, François de Rougemont, Philippe Couplet, eds. and trans. (1687) Confucius Sinarum philosophus. Daniel Horthemels, Paris.

-

Jordaine J (1687) Duodecimal arithmetick. John Richardson, London

-

Kempe M (2022) Die beste aller möglichen Welten: Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in seiner Zeit. S. Fischer, Frankfurt

-

Knobloch E (2018) Determinant theory, symmetric functions, and dyadic. In: Antognazza MR (ed) The Oxford handbook of Leibniz. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 225–246

-

Knuth DE (1983) History of binary and other nondecimal numeration. By Anton Glaser. Los Angeles, CA (Tomash Publishers). 1981. 218 + xiii pp.” Historia Mathematica 10: 236–243.

-

Knuth DE (1998) The art of computer programming. Volume 2: Seminumerical algorithms, 3rd edn. Addison–Wesley, Upper Saddle River

-

Kolpas S (2019) Napier’s Binary chessboard calculator. Math Horiz 27:25–27

MathSciNet

-

LBr = Manuscript held by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Bibliothek – Niedersächsische Landesbibliothek, Hanover, Germany. Cited by shelfmark and Blatt [sheet]

-

Leibniz GW (1675) Extrait d’une lettre de Mr. Leibniz à l’auteur du journal, touchant le principe de justesse des horloges portatives de son invention. J des sçavans:93–96

-

Leibniz GW (1678) Extrait d’une lettre ecrite d’Hanovre par M. de Leibniz à l’Auteur du Journal, contenant une observation nouvelle de la maniere d’essayer si un nombre est primitif. J des sçavans:75–76

-

Leibniz GW (1768) Opera Omnia. Edited by Louis Dutens. 6 vols. Fratres de Tournes, Geneva

-

Leibniz GW. (1849–1863) Leibniziens Mathematische Schriften. Edited by C. I. Gerhardt. 7 vols. H. W. Schmidt, Halle

-

Leibniz GW (1923–.) Sämtliche Schriften und Briefe. Edited by Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften. 8 series, each divided into multiple volumes. Akademie Verlag, Berlin

-

Leibniz GW (1969) Philosophical papers and letters, ed. and trans. Leroy E. Loemker. D. Reidel, Dordrecht

-

Leibniz GW (1971) Calcolo con zero e uno. Translated by Lia Ruffino. Etas Kompass, Milan

-

Leibniz GW (1985) Theodicy. Translated by E. M. Huggard. Open Court, Chicago

-

Leibniz GW (2006) Shorter Leibniz texts. Edited and translated by Lloyd Strickland. Continuum, London

-

LH = Manuscript held by Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz Bibliothek – Niedersächsische Landesbibliothek, Hanover, Germany. Cited by shelfmark and Blatt [sheet]

-

Mahnke, Dietrich. 1912–13. Leibniz auf der Suche nach einer allgemeinen Primzahlgleichung,” Bibliotheca Math. 13:29–61.

-

Mersenne M (1644) Cogitata physico mathematica. In quibus naturae quam artis effectus admirandi certissimis demonstrationibus explicantur. Bertier, Paris

-

Morley FV (1922) Thomas Hariot—1560–1621. Sci Mon 14(1):60–66

-

Napier J (1617) Rabdologiæ. Andreas Hart, Edinburgh

-

Nystrom JW (1862) Project of a new system of arithmetic, weight, measure and coins, proposed to be called the tonal system, with sixteen to the base. J. B. Lippincott & Co, Philadelphia

-

Nystrom JW (1863) On a new system of arithmetic and metrology, called the tonal system. J Franklin Institute 76:263–275, 337–348, 402–407

-

Pascal B (1665) Traité du triangle arithmetique, avec quelques autres petits traitez sur la mesme materiere. Guillaume Desprez, Paris

-

Pauli JW (1678) Disputatione mathematica numerum perfectum perfectissimi. Georg, Leipzig

-

Ramus P (1599) Arithmetica et geometria. Claude Marnium and Johannes Aubrium, Frankfurt

-

Riese A (1529) Rechnung auff der Linihen und Federn, n.p., Erfurt

-

Scaliger, JC (1557) Exotericarum exercitationum liber quintus decimus, de subtilitate, ad Hieronymum Cardanum. Michael Vasocsani, Paris

-

Schott G (1658) Magia universalis naturae & artis. Operis quadripartiti. Tomus tertius & quartus. Johann Gottfried Schönwetter, Frankfurt

-

Schwenter D (1636) Deliciae physico-mathematicae oder Mathematische und philosophische Erquickstunden. Dümmler, Nuremberg

-

Serra Y (2010a) Le manuscrit «De Progressione Dyadica» de Leibniz. http://www.bibnum.education.fr/sites/default/files/leibniz-analyse.pdf

-

Serra Y (2010b) Traduction du fac-similé du manuscrit de Leibniz du 15 mars 1679, «De Progressione Dyadica». http://www.bibnum.education.fr/sites/default/files/leibniz-numeration-texte.pdf

-

Stein E, Kopp FO, Wiechmann K, Weber G (2006) Neue Forschungsergebnisse und Nachbauten zur Vier-Spezies- Rechenmaschine und zur Dyadischen Rechenmaschine nach Leibniz. In: VIII. Internat. Leibniz-Kongress, Vorträge 2. Teil, 1018–1025. Hannover

-

Stifel M (1544) Arithmetica integra. Johan. Petreium, Nuremberg

-

Strickland L (2014) Leibniz’s monadology: a new translation and guide. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh

Book

-

Strickland, L (2022) An unpublished manuscript of Leibniz’s on duodecimal. The Duodecimal Bulletin 54: 20z–26z

-

Strickland L (2023a) How Leibniz tried to tell the world he had squared the circle. Hist Math 62:19–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hm.2022.08.004

-

Strickland L (2023b) Leibniz’s tactile binary clock. L.I.S.A. Wissenschaftsportal Gerda Henkel Stiftung. https://lisa.gerda-henkel-stiftung.de/leibnitzstactileclock

-

Strickland L (2023c) Why did Thomas Harriot invent binary? Math Intell. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00283-023-10271-9

-

Strickland L, Jones OD (2023) F things you (probably) didn’t know about hexadecimal. Math Intell. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00283-022-10206-w

-

Strickland L, Lewis H (2022) Leibniz on binary: the invention of computer arithmetic. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

-

Swetz, Frank J. 2003. Leibniz, the Yijing, and the Religious conversion of the Chinese. Math Mag 76 (4): 276–291.

-

Sypniewski, Bernard Paul. 2005. China and universals: Leibniz, binary mathematics, and the Yijing Hexagrams Monumenta Serica 53:287–314.

-

Tropfke J (1980) Geschichte der Elementarmathematik. Band 1: Arithmetik und Algebra, 4th edn. De Gruyter, Berlin

-

von Mackensen L (1974) Leibniz als Ahnherr der Kybernetik—ein bisher unbekannter Leibnizscher Vorschlag einer ‘Machina arithmeticae dyadicae’. In: Akten des II Internationalen Leibniz-Kongresses, II:255–268. Steiner Verlag, Wiesbaden

-

Weigel E (1673) Tetractys, Summum tum Arithmeticae tum Philosophiae discursivae compendium, artis magnae sciendi. Meyer, Jena

-

Zacher HJ (ed) (1973) Die Hauptschriften zur Dyadik von G. W. Leibniz. Vittorio Klostermann, Frankfurt

-

Zhonglian S (2000) Leibniz’s binary system and Shao Yong’s Xiantiantu. In: Li W, Poser H (eds) Das Neueste über China: G.W. Leibnizens Novissima Sinica von 1697. Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart, pp 165–169

Acknowledgments

The author would like to express his gratitude to the Gerda Henkel Stiftung, Düsseldorf, for their award of a research scholarship (AZ 46/V/21), which made this chapter possible. The author would also like to thank Daniel J. Cook, Donald E. Knuth, and Harry R. Lewis for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this chapter; Siegmund Probst and Julia Weckend for their assistance in transcribing manuscripts and their illuminating discussion thereof; and Lisa Silva – @lisa_cs8 – for her illustration of Leibniz’s tactile clock.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

- History, Politics, and Philosophy, Manchester Metropolitan University, Manchester, UK

Lloyd Strickland

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lloyd Strickland.

via:

-

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz: How the ‘I Ching’ Inspired His Binary System

https://www.inverse.com/article/46593-gottfried-wilhelm-leibniz-i-ching-binary-system

-

Leibniz on Number Systems | SpringerLink

https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-3-030-19071-2_90-1

-

Why Decimal System and Binary System Are the Most Widely Used: A Possible Explanation.pdf

224

224

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?