4. Installing a Binary Distribution

4.3. Installing a pinned Nix version from a URL

4.4. Installing from a binary tarball

5.2. Obtaining a Source Distribution

7.1.1. NIX_SSL_CERT_FILE with macOS and the Nix daemon

13. Sharing Packages Between Machines

13.1. Serving a Nix store via HTTP

13.2. Copying Closures Via SSH

13.3. Serving a Nix store via SSH

13.4. Serving a Nix store via AWS S3 or S3-compatible Service

13.4.1. Anonymous Reads to your S3-compatible binary cache

13.4.2. Authenticated Reads to your S3 binary cache

13.4.3. Authenticated Writes to your S3-compatible binary cache

18. Common Environment Variables

nix-env — manipulate or query Nix user environments

nix-build — build a Nix expression

nix-shell — start an interactive shell based on a Nix expression

nix-store — manipulate or query the Nix store

nix-channel — manage Nix channels

nix-collect-garbage — delete unreachable store paths

nix-copy-closure — copy a closure to or from a remote machine via SSH

nix-daemon — Nix multi-user support daemon

nix-hash — compute the cryptographic hash of a path

nix-instantiate — instantiate store derivations from Nix expressions

nix-prefetch-url — copy a file from a URL into the store and print its hash

nix.conf — Nix configuration file

C.4. Release 1.11.10 (2017-06-12)

C.5. Release 1.11 (2016-01-19)

C.6. Release 1.10 (2015-09-03)

C.10. Release 1.6.1 (2013-10-28)

C.11. Release 1.6 (2013-09-10)

C.12. Release 1.5.2 (2013-05-13)

C.13. Release 1.5 (2013-02-27)

C.14. Release 1.4 (2013-02-26)

C.15. Release 1.3 (2013-01-04)

C.16. Release 1.2 (2012-12-06)

C.17. Release 1.1 (2012-07-18)

C.18. Release 1.0 (2012-05-11)

C.19. Release 0.16 (2010-08-17)

C.20. Release 0.15 (2010-03-17)

C.21. Release 0.14 (2010-02-04)

C.22. Release 0.13 (2009-11-05)

C.23. Release 0.12 (2008-11-20)

C.24. Release 0.11 (2007-12-31)

C.25. Release 0.10.1 (2006-10-11)

C.26. Release 0.10 (2006-10-06)

C.27. Release 0.9.2 (2005-09-21)

C.28. Release 0.9.1 (2005-09-20)

C.29. Release 0.9 (2005-09-16)

C.30. Release 0.8.1 (2005-04-13)

C.31. Release 0.8 (2005-04-11)

C.32. Release 0.7 (2005-01-12)

C.33. Release 0.6 (2004-11-14)

Part I. Introduction

Chapter 1. About Nix

Nix is a purely functional package manager. This means that it treats packages like values in purely functional programming languages such as Haskell — they are built by functions that don’t have side-effects, and they never change after they have been built. Nix stores packages in the Nix store, usually the directory /nix/store, where each package has its own unique subdirectory such as

/nix/store/b6gvzjyb2pg0kjfwrjmg1vfhh54ad73z-firefox-33.1/

where b6gvzjyb2pg0… is a unique identifier for the package that captures all its dependencies (it’s a cryptographic hash of the package’s build dependency graph). This enables many powerful features.

Multiple versions

You can have multiple versions or variants of a package installed at the same time. This is especially important when different applications have dependencies on different versions of the same package — it prevents the “DLL hell”. Because of the hashing scheme, different versions of a package end up in different paths in the Nix store, so they don’t interfere with each other.

An important consequence is that operations like upgrading or uninstalling an application cannot break other applications, since these operations never “destructively” update or delete files that are used by other packages.

Complete dependencies

Nix helps you make sure that package dependency specifications are complete. In general, when you’re making a package for a package management system like RPM, you have to specify for each package what its dependencies are, but there are no guarantees that this specification is complete. If you forget a dependency, then the package will build and work correctly on your machine if you have the dependency installed, but not on the end user's machine if it's not there.

Since Nix on the other hand doesn’t install packages in “global” locations like /usr/bin but in package-specific directories, the risk of incomplete dependencies is greatly reduced. This is because tools such as compilers don’t search in per-packages directories such as /nix/store/5lbfaxb722zp…-openssl-0.9.8d/include, so if a package builds correctly on your system, this is because you specified the dependency explicitly. This takes care of the build-time dependencies.

Once a package is built, runtime dependencies are found by scanning binaries for the hash parts of Nix store paths (such as r8vvq9kq…). This sounds risky, but it works extremely well.

Multi-user support

Nix has multi-user support. This means that non-privileged users can securely install software. Each user can have a different profile, a set of packages in the Nix store that appear in the user’s PATH. If a user installs a package that another user has already installed previously, the package won’t be built or downloaded a second time. At the same time, it is not possible for one user to inject a Trojan horse into a package that might be used by another user.

Atomic upgrades and rollbacks

Since package management operations never overwrite packages in the Nix store but just add new versions in different paths, they are atomic. So during a package upgrade, there is no time window in which the package has some files from the old version and some files from the new version — which would be bad because a program might well crash if it’s started during that period.

And since packages aren’t overwritten, the old versions are still there after an upgrade. This means that you can roll back to the old version:

$ nix-env --upgrade some-packages

$ nix-env --rollback

Garbage collection

When you uninstall a package like this…

$ nix-env --uninstall firefox

the package isn’t deleted from the system right away (after all, you might want to do a rollback, or it might be in the profiles of other users). Instead, unused packages can be deleted safely by running the garbage collector:

$ nix-collect-garbage

This deletes all packages that aren’t in use by any user profile or by a currently running program.

Functional package language

Packages are built from Nix expressions, which is a simple functional language. A Nix expression describes everything that goes into a package build action (a “derivation”): other packages, sources, the build script, environment variables for the build script, etc. Nix tries very hard to ensure that Nix expressions are deterministic: building a Nix expression twice should yield the same result.

Because it’s a functional language, it’s easy to support building variants of a package: turn the Nix expression into a function and call it any number of times with the appropriate arguments. Due to the hashing scheme, variants don’t conflict with each other in the Nix store.

Transparent source/binary deployment

Nix expressions generally describe how to build a package from source, so an installation action like

$ nix-env --install firefox

could cause quite a bit of build activity, as not only Firefox but also all its dependencies (all the way up to the C library and the compiler) would have to built, at least if they are not already in the Nix store. This is a source deployment model. For most users, building from source is not very pleasant as it takes far too long. However, Nix can automatically skip building from source and instead use a binary cache, a web server that provides pre-built binaries. For instance, when asked to build /nix/store/b6gvzjyb2pg0…-firefox-33.1 from source, Nix would first check if the file https://cache.nixos.org/b6gvzjyb2pg0….narinfo exists, and if so, fetch the pre-built binary referenced from there; otherwise, it would fall back to building from source.

Nix Packages collection

We provide a large set of Nix expressions containing hundreds of existing Unix packages, the Nix Packages collection (Nixpkgs).

Managing build environments

Nix is extremely useful for developers as it makes it easy to automatically set up the build environment for a package. Given a Nix expression that describes the dependencies of your package, the command nix-shell will build or download those dependencies if they’re not already in your Nix store, and then start a Bash shell in which all necessary environment variables (such as compiler search paths) are set.

For example, the following command gets all dependencies of the Pan newsreader, as described by its Nix expression:

$ nix-shell '<nixpkgs>' -A pan

You’re then dropped into a shell where you can edit, build and test the package:

[nix-shell]$ tar xf $src [nix-shell]$ cd pan-* [nix-shell]$ ./configure [nix-shell]$ make [nix-shell]$ ./pan/gui/pan

Portability

Nix runs on Linux and macOS.

NixOS

NixOS is a Linux distribution based on Nix. It uses Nix not just for package management but also to manage the system configuration (e.g., to build configuration files in /etc). This means, among other things, that it is easy to roll back the entire configuration of the system to an earlier state. Also, users can install software without root privileges. For more information and downloads, see the NixOS homepage.

License

Nix is released under the terms of the GNU LGPLv2.1 or (at your option) any later version.

Chapter 2. Quick Start

This chapter is for impatient people who don't like reading documentation. For more in-depth information you are kindly referred to subsequent chapters.

-

Install single-user Nix by running the following:

$ bash <(curl https://nixos.org/nix/install)

This will install Nix in

/nix. The install script will create/nixusing sudo, so make sure you have sufficient rights. (For other installation methods, see Part II, “Installation”.) -

See what installable packages are currently available in the channel:

$ nix-env -qa docbook-xml-4.3 docbook-xml-4.5 firefox-33.0.2 hello-2.9 libxslt-1.1.28

... -

Install some packages from the channel:

$ nix-env -i hello

This should download pre-built packages; it should not build them locally (if it does, something went wrong).

-

Test that they work:

$ which hello /home/eelco/.nix-profile/bin/hello $ hello Hello, world!

-

Uninstall a package:

$ nix-env -e hello

-

You can also test a package without installing it:

$ nix-shell -p hello

This builds or downloads GNU Hello and its dependencies, then drops you into a Bash shell where the hello command is present, all without affecting your normal environment:

[nix-shell:~]$ hello Hello, world! [nix-shell:~]$ exit $ hello hello: command not found

-

To keep up-to-date with the channel, do:

$ nix-channel --update nixpkgs $ nix-env -u '*'

The latter command will upgrade each installed package for which there is a “newer” version (as determined by comparing the version numbers).

-

If you're unhappy with the result of a nix-env action (e.g., an upgraded package turned out not to work properly), you can go back:

$ nix-env --rollback

-

You should periodically run the Nix garbage collector to get rid of unused packages, since uninstalls or upgrades don't actually delete them:

$ nix-collect-garbage -d

Part II. Installation

This section describes how to install and configure Nix for first-time use.

Chapter 3. Supported Platforms

Nix is currently supported on the following platforms:

-

Linux (i686, x86_64, aarch64).

-

macOS (x86_64).

Chapter 4. Installing a Binary Distribution

If you are using Linux or macOS, the easiest way to install Nix is to run the following command:

$ sh <(curl https://nixos.org/nix/install)

As of Nix 2.1.0, the Nix installer will always default to creating a single-user installation, however opting in to the multi-user installation is highly recommended.

4.1. Single User Installation

To explicitly select a single-user installation on your system:

sh <(curl https://nixos.org/nix/install) --no-daemon

This will perform a single-user installation of Nix, meaning that /nix is owned by the invoking user. You should run this under your usual user account, not as root. The script will invoke sudo to create /nix if it doesn’t already exist. If you don’t have sudo, you should manually create /nix first as root, e.g.:

$ mkdir /nix $ chown alice /nix

The install script will modify the first writable file from amongst .bash_profile, .bash_login and .profile to source ~/.nix-profile/etc/profile.d/nix.sh. You can set the NIX_INSTALLER_NO_MODIFY_PROFILE environment variable before executing the install script to disable this behaviour.

You can uninstall Nix simply by running:

$ rm -rf /nix

4.2. Multi User Installation

The multi-user Nix installation creates system users, and a system service for the Nix daemon.

Supported Systems

-

Linux running systemd, with SELinux disabled

-

macOS

You can instruct the installer to perform a multi-user installation on your system:

sh <(curl https://nixos.org/nix/install) --daemon

The multi-user installation of Nix will create build users between the user IDs 30001 and 30032, and a group with the group ID 30000. You should run this under your usual user account, notas root. The script will invoke sudo as needed.

Note: If you need Nix to use a different group ID or user ID set, you will have to download the tarball manually and edit the install script.

The installer will modify /etc/bashrc, and /etc/zshrc if they exist. The installer will first back up these files with a .backup-before-nix extension. The installer will also create /etc/profile.d/nix.sh.

You can uninstall Nix with the following commands:

sudo rm -rf /etc/profile/nix.sh /etc/nix /nix ~root/.nix-profile ~root/.nix-defexpr ~root/.nix-channels ~/.nix-profile ~/.nix-defexpr ~/.nix-channels # If you are on Linux with systemd, you will need to run: sudo systemctl stop nix-daemon.socket sudo systemctl stop nix-daemon.service sudo systemctl disable nix-daemon.socket sudo systemctl disable nix-daemon.service sudo systemctl daemon-reload # If you are on macOS, you will need to run: sudo launchctl unload /Library/LaunchDaemons/org.nixos.nix-daemon.plist sudo rm /Library/LaunchDaemons/org.nixos.nix-daemon.plist

There may also be references to Nix in /etc/profile, /etc/bashrc, and /etc/zshrc which you may remove.

4.3. Installing a pinned Nix version from a URL

NixOS.org hosts version-specific installation URLs for all Nix versions since 1.11.16, at https://nixos.org/releases/nix/nix-VERSION/install.

These install scripts can be used the same as the main NixOS.org installation script:

sh <(curl https://nixos.org/nix/install)

In the same directory of the install script are sha256 sums, and gpg signature files.

4.4. Installing from a binary tarball

You can also download a binary tarball that contains Nix and all its dependencies. (This is what the install script at https://nixos.org/nix/install does automatically.) You should unpack it somewhere (e.g. in /tmp), and then run the script named install inside the binary tarball:

alice$ cd /tmp alice$ tar xfj nix-1.8-x86_64-darwin.tar.bz2 alice$ cd nix-1.8-x86_64-darwin alice$ ./install

If you need to edit the multi-user installation script to use different group ID or a different user ID range, modify the variables set in the file named install-multi-user.

Chapter 5. Installing Nix from Source

If no binary package is available, you can download and compile a source distribution.

5.1. Prerequisites

-

GNU Make.

-

Bash Shell. The

./configurescript relies on bashisms, so Bash is required. -

A version of GCC or Clang that supports C++14.

-

pkg-config to locate dependencies. If your distribution does not provide it, you can get it from http://www.freedesktop.org/wiki/Software/pkg-config.

-

The OpenSSL library to calculate cryptographic hashes. If your distribution does not provide it, you can get it from https://www.openssl.org.

-

The

libbrotliencandlibbrotlideclibraries to provide implementation of the Brotli compression algorithm. They are available for download from the official repository https://github.com/google/brotli. -

The bzip2 compressor program and the

libbz2library. Thus you must have bzip2 installed, including development headers and libraries. If your distribution does not provide these, you can obtain bzip2 from https://web.archive.org/web/20180624184756/http://www.bzip.org/. -

liblzma, which is provided by XZ Utils. If your distribution does not provide this, you can get it from https://tukaani.org/xz/. -

cURL and its library. If your distribution does not provide it, you can get it from https://curl.haxx.se/.

-

The SQLite embedded database library, version 3.6.19 or higher. If your distribution does not provide it, please install it from http://www.sqlite.org/.

-

The Boehm garbage collector to reduce the evaluator’s memory consumption (optional). To enable it, install

pkgconfigand the Boehm garbage collector, and pass the flag--enable-gcto configure. -

The

boostlibrary of version 1.66.0 or higher. It can be obtained from the official web site https://www.boost.org/. -

The xmllint and xsltproc programs to build this manual and the man-pages. These are part of the

libxml2andlibxsltpackages, respectively. You also need the DocBook XSL stylesheets and optionally the DocBook 5.0 RELAX NG schemas. Note that these are only required if you modify the manual sources or when you are building from the Git repository. -

Recent versions of Bison and Flex to build the parser. (This is because Nix needs GLR support in Bison and reentrancy support in Flex.) For Bison, you need version 2.6, which can be obtained from the GNU FTP server. For Flex, you need version 2.5.35, which is available on SourceForge. Slightly older versions may also work, but ancient versions like the ubiquitous 2.5.4a won't. Note that these are only required if you modify the parser or when you are building from the Git repository.

-

The

libseccompis used to provide syscall filtering on Linux. This is an optional dependency and can be disabled passing a--disable-seccomp-sandboxingoption to the configurescript (Not recommended unless your system doesn't supportlibseccomp). To get the library, visit https://github.com/seccomp/libseccomp.

5.2. Obtaining a Source Distribution

The source tarball of the most recent stable release can be downloaded from the Nix homepage. You can also grab the most recent development release.

Alternatively, the most recent sources of Nix can be obtained from its Git repository. For example, the following command will check out the latest revision into a directory called nix:

$ git clone https://github.com/NixOS/nix

Likewise, specific releases can be obtained from the tags of the repository.

5.3. Building Nix from Source

After unpacking or checking out the Nix sources, issue the following commands:

$ ./configure options...

$ make

$ make install

Nix requires GNU Make so you may need to invoke gmake instead.

When building from the Git repository, these should be preceded by the command:

$ ./bootstrap.sh

The installation path can be specified by passing the --prefix= to configure. The default installation directory is prefix/usr/local. You can change this to any location you like. You must have write permission to the prefix path.

Nix keeps its store (the place where packages are stored) in /nix/store by default. This can be changed using --with-store-dir=.path

Warning: It is best not to change the Nix store from its default, since doing so makes it impossible to use pre-built binaries from the standard Nixpkgs channels — that is, all packages will need to be built from source.

Nix keeps state (such as its database and log files) in /nix/var by default. This can be changed using --localstatedir=.path

Chapter 6. Security

Nix has two basic security models. First, it can be used in “single-user mode”, which is similar to what most other package management tools do: there is a single user (typically root) who performs all package management operations. All other users can then use the installed packages, but they cannot perform package management operations themselves.

Alternatively, you can configure Nix in “multi-user mode”. In this model, all users can perform package management operations — for instance, every user can install software without requiring root privileges. Nix ensures that this is secure. For instance, it’s not possible for one user to overwrite a package used by another user with a Trojan horse.

6.1. Single-User Mode

In single-user mode, all Nix operations that access the database in prefix/var/nix/dbprefix/storeroot. (If you install from RPM packages, that’s in fact the default ownership.) However, on single-user machines, it is often convenient to chown those directories to your normal user account so that you don’t have to su to root all the time.

6.2. Multi-User Mode

To allow a Nix store to be shared safely among multiple users, it is important that users are not able to run builders that modify the Nix store or database in arbitrary ways, or that interfere with builds started by other users. If they could do so, they could install a Trojan horse in some package and compromise the accounts of other users.

To prevent this, the Nix store and database are owned by some privileged user (usually root) and builders are executed under special user accounts (usually named nixbld1, nixbld2, etc.). When a unprivileged user runs a Nix command, actions that operate on the Nix store (such as builds) are forwarded to a Nix daemon running under the owner of the Nix store/database that performs the operation.

Note: Multi-user mode has one important limitation: only root and a set of trusted users specified in nix.conf can specify arbitrary binary caches. So while unprivileged users may install packages from arbitrary Nix expressions, they may not get pre-built binaries.

Setting up the build users

The build users are the special UIDs under which builds are performed. They should all be members of the build users group nixbld. This group should have no other members. The build users should not be members of any other group. On Linux, you can create the group and users as follows:

$ groupadd -r nixbld

$ for n in $(seq 1 10); do useradd -c "Nix build user $n" \

-d /var/empty -g nixbld -G nixbld -M -N -r -s "$(which nologin)" \

nixbld$n; done

This creates 10 build users. There can never be more concurrent builds than the number of build users, so you may want to increase this if you expect to do many builds at the same time.

Running the daemon

The Nix daemon should be started as follows (as root):

$ nix-daemon

You’ll want to put that line somewhere in your system’s boot scripts.

To let unprivileged users use the daemon, they should set the NIX_REMOTE environment variable to daemon. So you should put a line like

export NIX_REMOTE=daemon

into the users’ login scripts.

Restricting access

To limit which users can perform Nix operations, you can use the permissions on the directory /nix/var/nix/daemon-socket. For instance, if you want to restrict the use of Nix to the members of a group called nix-users, do

$ chgrp nix-users /nix/var/nix/daemon-socket $ chmod ug=rwx,o= /nix/var/nix/daemon-socket

This way, users who are not in the nix-users group cannot connect to the Unix domain socket /nix/var/nix/daemon-socket/socket, so they cannot perform Nix operations.

Chapter 7. Environment Variables

To use Nix, some environment variables should be set. In particular, PATH should contain the directories prefix/bin~/.nix-profile/bin. The first directory contains the Nix tools themselves, while ~/.nix-profile is a symbolic link to the current user environment (an automatically generated package consisting of symlinks to installed packages). The simplest way to set the required environment variables is to include the file prefix/etc/profile.d/nix.sh~/.profile (or similar), like this:

source prefix/etc/profile.d/nix.sh

7.1. NIX_SSL_CERT_FILE

If you need to specify a custom certificate bundle to account for an HTTPS-intercepting man in the middle proxy, you must specify the path to the certificate bundle in the environment variable NIX_SSL_CERT_FILE.

If you don't specify a NIX_SSL_CERT_FILE manually, Nix will install and use its own certificate bundle.

-

Set the environment variable and install Nix

$ export NIX_SSL_CERT_FILE=/etc/ssl/my-certificate-bundle.crt $ sh <(curl https://nixos.org/nix/install)

-

In the shell profile and rc files (for example,

/etc/bashrc,/etc/zshrc), add the following line:export NIX_SSL_CERT_FILE=/etc/ssl/my-certificate-bundle.crt

Note: You must not add the export and then do the install, as the Nix installer will detect the presense of Nix configuration, and abort.

7.1.1. NIX_SSL_CERT_FILE with macOS and the Nix daemon

On macOS you must specify the environment variable for the Nix daemon service, then restart it:

$ sudo launchctl setenv NIX_SSL_CERT_FILE /etc/ssl/my-certificate-bundle.crt $ sudo launchctl kickstart -k system/org.nixos.nix-daemon

Chapter 8. Upgrading Nix

Multi-user Nix users on macOS can upgrade Nix by running: sudo -i sh -c 'nix-channel --update && nix-env -iA nixpkgs.nix && launchctl remove org.nixos.nix-daemon && launchctl load /Library/LaunchDaemons/org.nixos.nix-daemon.plist'

Single-user installations of Nix should run this: nix-channel --update; nix-env -iA nixpkgs.nix

Part III. Package Management

This chapter discusses how to do package management with Nix, i.e., how to obtain, install, upgrade, and erase packages. This is the “user’s” perspective of the Nix system — people who want to create packages should consult Part IV, “Writing Nix Expressions”.

Chapter 9. Basic Package Management

The main command for package management is nix-env. You can use it to install, upgrade, and erase packages, and to query what packages are installed or are available for installation.

In Nix, different users can have different “views” on the set of installed applications. That is, there might be lots of applications present on the system (possibly in many different versions), but users can have a specific selection of those active — where “active” just means that it appears in a directory in the user’s PATH. Such a view on the set of installed applications is called a user environment, which is just a directory tree consisting of symlinks to the files of the active applications.

Components are installed from a set of Nix expressions that tell Nix how to build those packages, including, if necessary, their dependencies. There is a collection of Nix expressions called the Nix Package collection that contains packages ranging from basic development stuff such as GCC and Glibc, to end-user applications like Mozilla Firefox. (Nix is however not tied to the Nix Package collection; you could write your own Nix expressions based on it, or completely new ones.)

You can manually download the latest version of Nixpkgs from http://nixos.org/nixpkgs/download.html. However, it’s much more convenient to use the Nixpkgs channel, since it makes it easy to stay up to date with new versions of Nixpkgs. (Channels are described in more detail in Chapter 12, Channels.) Nixpkgs is automatically added to your list of “subscribed” channels when you install Nix. If this is not the case for some reason, you can add it as follows:

$ nix-channel --add https://nixos.org/channels/nixpkgs-unstable $ nix-channel --update

Note: On NixOS, you’re automatically subscribed to a NixOS channel corresponding to your NixOS major release (e.g. http://nixos.org/channels/nixos-14.12). A NixOS channel is identical to the Nixpkgs channel, except that it contains only Linux binaries and is updated only if a set of regression tests succeed.

You can view the set of available packages in Nixpkgs:

$ nix-env -qa aterm-2.2 bash-3.0 binutils-2.15 bison-1.875d blackdown-1.4.2 bzip2-1.0.2 …

The flag -q specifies a query operation, and -a means that you want to show the “available” (i.e., installable) packages, as opposed to the installed packages. If you downloaded Nixpkgs yourself, or if you checked it out from GitHub, then you need to pass the path to your Nixpkgs tree using the -f flag:

$ nix-env -qaf /path/to/nixpkgs

where /path/to/nixpkgs is where you’ve unpacked or checked out Nixpkgs.

You can select specific packages by name:

$ nix-env -qa firefox firefox-34.0.5 firefox-with-plugins-34.0.5

and using regular expressions:

$ nix-env -qa 'firefox.*'

It is also possible to see the status of available packages, i.e., whether they are installed into the user environment and/or present in the system:

$ nix-env -qas … -PS bash-3.0 --S binutils-2.15 IPS bison-1.875d …

The first character (I) indicates whether the package is installed in your current user environment. The second (P) indicates whether it is present on your system (in which case installing it into your user environment would be a very quick operation). The last one (S) indicates whether there is a so-called substitute for the package, which is Nix’s mechanism for doing binary deployment. It just means that Nix knows that it can fetch a pre-built package from somewhere (typically a network server) instead of building it locally.

You can install a package using nix-env -i. For instance,

$ nix-env -i subversion

will install the package called subversion (which is, of course, the Subversion version management system).

Note: When you ask Nix to install a package, it will first try to get it in pre-compiled form from a binary cache. By default, Nix will use the binary cache https://cache.nixos.org; it contains binaries for most packages in Nixpkgs. Only if no binary is available in the binary cache, Nix will build the package from source. So if nix-env -i subversion results in Nix building stuff from source, then either the package is not built for your platform by the Nixpkgs build servers, or your version of Nixpkgs is too old or too new. For instance, if you have a very recent checkout of Nixpkgs, then the Nixpkgs build servers may not have had a chance to build everything and upload the resulting binaries tohttps://cache.nixos.org. The Nixpkgs channel is only updated after all binaries have been uploaded to the cache, so if you stick to the Nixpkgs channel (rather than using a Git checkout of the Nixpkgs tree), you will get binaries for most packages.

Naturally, packages can also be uninstalled:

$ nix-env -e subversion

Upgrading to a new version is just as easy. If you have a new release of Nix Packages, you can do:

$ nix-env -u subversion

This will only upgrade Subversion if there is a “newer” version in the new set of Nix expressions, as defined by some pretty arbitrary rules regarding ordering of version numbers (which generally do what you’d expect of them). To just unconditionally replace Subversion with whatever version is in the Nix expressions, use -i instead of -u; -i will remove whatever version is already installed.

You can also upgrade all packages for which there are newer versions:

$ nix-env -u

Sometimes it’s useful to be able to ask what nix-env would do, without actually doing it. For instance, to find out what packages would be upgraded by nix-env -u, you can do

$ nix-env -u --dry-run (dry run; not doing anything) upgrading `libxslt-1.1.0' to `libxslt-1.1.10' upgrading `graphviz-1.10' to `graphviz-1.12' upgrading `coreutils-5.0' to `coreutils-5.2.1'

Chapter 10. Profiles

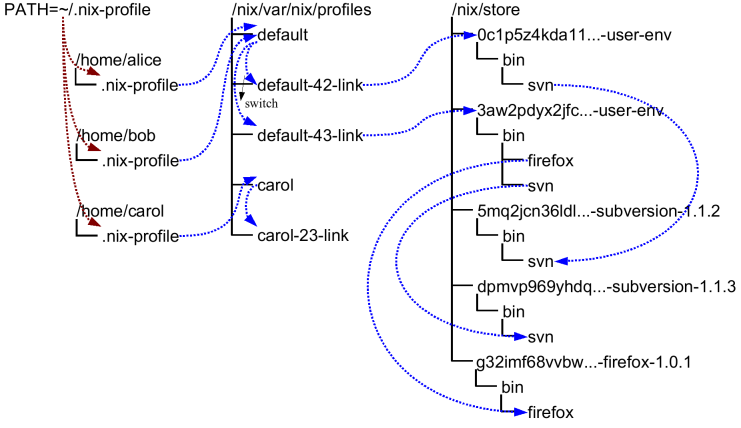

Profiles and user environments are Nix’s mechanism for implementing the ability to allow different users to have different configurations, and to do atomic upgrades and rollbacks. To understand how they work, it’s useful to know a bit about how Nix works. In Nix, packages are stored in unique locations in the Nix store (typically, /nix/store). For instance, a particular version of the Subversion package might be stored in a directory /nix/store/dpmvp969yhdqs7lm2r1a3gng7pyq6vy4-subversion-1.1.3/, while another version might be stored in/nix/store/5mq2jcn36ldlmh93yj1n8s9c95pj7c5s-subversion-1.1.2. The long strings prefixed to the directory names are cryptographic hashes[1] of all inputs involved in building the package — sources, dependencies, compiler flags, and so on. So if two packages differ in any way, they end up in different locations in the file system, so they don’t interfere with each other. Figure 10.1, “User environments” shows a part of a typical Nix store.

Figure 10.1. User environments

Of course, you wouldn’t want to type

$ /nix/store/dpmvp969yhdq...-subversion-1.1.3/bin/svn

every time you want to run Subversion. Of course we could set up the PATH environment variable to include the bin directory of every package we want to use, but this is not very convenient since changing PATH doesn’t take effect for already existing processes. The solution Nix uses is to create directory trees of symlinks to activated packages. These are called user environments and they are packages themselves (though automatically generated by nix-env), so they too reside in the Nix store. For instance, in Figure 10.1, “User environments” the user environment /nix/store/0c1p5z4kda11...-user-env contains a symlink to just Subversion 1.1.2 (arrows in the figure indicate symlinks). This would be what we would obtain if we had done

$ nix-env -i subversion

on a set of Nix expressions that contained Subversion 1.1.2.

This doesn’t in itself solve the problem, of course; you wouldn’t want to type /nix/store/0c1p5z4kda11...-user-env/bin/svn either. That’s why there are symlinks outside of the store that point to the user environments in the store; for instance, the symlinks default-42-link and default-43-link in the example. These are called generations since every time you perform a nix-env operation, a new user environment is generated based on the current one. For instance, generation 43 was created from generation 42 when we did

$ nix-env -i subversion firefox

on a set of Nix expressions that contained Firefox and a new version of Subversion.

Generations are grouped together into profiles so that different users don’t interfere with each other if they don’t want to. For example:

$ ls -l /nix/var/nix/profiles/ ... lrwxrwxrwx 1 eelco ... default-42-link -> /nix/store/0c1p5z4kda11...-user-env lrwxrwxrwx 1 eelco ... default-43-link -> /nix/store/3aw2pdyx2jfc...-user-env lrwxrwxrwx 1 eelco ... default -> default-43-link

This shows a profile called default. The file default itself is actually a symlink that points to the current generation. When we do a nix-env operation, a new user environment and generation link are created based on the current one, and finally the default symlink is made to point at the new generation. This last step is atomic on Unix, which explains how we can do atomic upgrades. (Note that the building/installing of new packages doesn’t interfere in any way with old packages, since they are stored in different locations in the Nix store.)

If you find that you want to undo a nix-env operation, you can just do

$ nix-env --rollback

which will just make the current generation link point at the previous link. E.g., default would be made to point at default-42-link. You can also switch to a specific generation:

$ nix-env --switch-generation 43

which in this example would roll forward to generation 43 again. You can also see all available generations:

$ nix-env --list-generations

You generally wouldn’t have /nix/var/nix/profiles/ in your some-profile/binPATH. Rather, there is a symlink ~/.nix-profile that points to your current profile. This means that you should put ~/.nix-profile/bin in your PATH (and indeed, that’s what the initialisation script /nix/etc/profile.d/nix.sh does). This makes it easier to switch to a different profile. You can do that using the command nix-env --switch-profile:

$ nix-env --switch-profile /nix/var/nix/profiles/my-profile $ nix-env --switch-profile /nix/var/nix/profiles/default

These commands switch to the my-profile and default profile, respectively. If the profile doesn’t exist, it will be created automatically. You should be careful about storing a profile in another location than the profiles directory, since otherwise it might not be used as a root of the garbage collector (see Chapter 11, Garbage Collection).

All nix-env operations work on the profile pointed to by ~/.nix-profile, but you can override this using the --profile option (abbreviation -p):

$ nix-env -p /nix/var/nix/profiles/other-profile -i subversion

This will not change the ~/.nix-profile symlink.

[1] 160-bit truncations of SHA-256 hashes encoded in a base-32 notation, to be precise.

Chapter 11. Garbage Collection

nix-env operations such as upgrades (-u) and uninstall (-e) never actually delete packages from the system. All they do (as shown above) is to create a new user environment that no longer contains symlinks to the “deleted” packages.

Of course, since disk space is not infinite, unused packages should be removed at some point. You can do this by running the Nix garbage collector. It will remove from the Nix store any package not used (directly or indirectly) by any generation of any profile.

Note however that as long as old generations reference a package, it will not be deleted. After all, we wouldn’t be able to do a rollback otherwise. So in order for garbage collection to be effective, you should also delete (some) old generations. Of course, this should only be done if you are certain that you will not need to roll back.

To delete all old (non-current) generations of your current profile:

$ nix-env --delete-generations old

Instead of old you can also specify a list of generations, e.g.,

$ nix-env --delete-generations 10 11 14

To delete all generations older than a specified number of days (except the current generation), use the d suffix. For example,

$ nix-env --delete-generations 14d

deletes all generations older than two weeks.

After removing appropriate old generations you can run the garbage collector as follows:

$ nix-store --gc

The behaviour of the gargage collector is affected by the keep- derivations (default: true) and keep-outputs (default: false) options in the Nix configuration file. The defaults will ensure that all derivations that are not build-time dependencies of garbage collector roots will be collected but that all output paths that are not runtime dependencies will be collected. (This is usually what you want, but while you are developing it may make sense to keep outputs to ensure that rebuild times are quick.) If you are feeling uncertain, you can also first view what files would be deleted:

$ nix-store --gc --print-dead

Likewise, the option --print-live will show the paths that won’t be deleted.

There is also a convenient little utility nix-collect-garbage, which when invoked with the -d (--delete-old) switch deletes all old generations of all profiles in /nix/var/nix/profiles. So

$ nix-collect-garbage -d

is a quick and easy way to clean up your system.

11.1. Garbage Collector Roots

The roots of the garbage collector are all store paths to which there are symlinks in the directory prefix/nix/var/nix/gcroots/nix/store/d718ef...-foo a root of the collector:

$ ln -s /nix/store/d718ef...-foo /nix/var/nix/gcroots/bar

That is, after this command, the garbage collector will not remove /nix/store/d718ef...-foo or any of its dependencies.

Subdirectories of prefix/nix/var/nix/gcroots

Chapter 12. Channels

If you want to stay up to date with a set of packages, it’s not very convenient to manually download the latest set of Nix expressions for those packages and upgrade using nix-env. Fortunately, there’s a better way: Nix channels.

A Nix channel is just a URL that points to a place that contains a set of Nix expressions and a manifest. Using the command nix-channel you can automatically stay up to date with whatever is available at that URL.

You can “subscribe” to a channel using nix-channel --add, e.g.,

$ nix-channel --add https://nixos.org/channels/nixpkgs-unstable

subscribes you to a channel that always contains that latest version of the Nix Packages collection. (Subscribing really just means that the URL is added to the file ~/.nix-channels, where it is read by subsequent calls to nix-channel --update.) You can “unsubscribe” using nix-channel --remove:

$ nix-channel --remove nixpkgs

To obtain the latest Nix expressions available in a channel, do

$ nix-channel --update

This downloads and unpacks the Nix expressions in every channel (downloaded from url/nixexprs.tar.bz2~/.nix-defexpr/channels). Consequently, you can then say

$ nix-env -u

to upgrade all packages in your profile to the latest versions available in the subscribed channels.

Chapter 13. Sharing Packages Between Machines

Sometimes you want to copy a package from one machine to another. Or, you want to install some packages and you know that another machine already has some or all of those packages or their dependencies. In that case there are mechanisms to quickly copy packages between machines.

13.1. Serving a Nix store via HTTP

You can easily share the Nix store of a machine via HTTP. This allows other machines to fetch store paths from that machine to speed up installations. It uses the same binary cachemechanism that Nix usually uses to fetch pre-built binaries from https://cache.nixos.org.

The daemon that handles binary cache requests via HTTP, nix-serve, is not part of the Nix distribution, but you can install it from Nixpkgs:

$ nix-env -i nix-serve

You can then start the server, listening for HTTP connections on whatever port you like:

$ nix-serve -p 8080

To check whether it works, try the following on the client:

$ curl http://avalon:8080/nix-cache-info

which should print something like:

StoreDir: /nix/store WantMassQuery: 1 Priority: 30

On the client side, you can tell Nix to use your binary cache using --option extra-binary-caches, e.g.:

$ nix-env -i firefox --option extra-binary-caches http://avalon:8080/

The option extra-binary-caches tells Nix to use this binary cache in addition to your default caches, such as https://cache.nixos.org. Thus, for any path in the closure of Firefox, Nix will first check if the path is available on the server avalon or another binary caches. If not, it will fall back to building from source.

You can also tell Nix to always use your binary cache by adding a line to the nix.conf configuration file like this:

binary-caches = http://avalon:8080/ https://cache.nixos.org/

13.2. Copying Closures Via SSH

The command nix-copy-closure copies a Nix store path along with all its dependencies to or from another machine via the SSH protocol. It doesn’t copy store paths that are already present on the target machine. For example, the following command copies Firefox with all its dependencies:

$ nix-copy-closure --to alice@itchy.example.org $(type -p firefox)

See nix-copy-closure(1) for details.

With nix-store --export and nix-store --import you can write the closure of a store path (that is, the path and all its dependencies) to a file, and then unpack that file into another Nix store. For example,

$ nix-store --export $(nix-store -qR $(type -p firefox)) > firefox.closure

writes the closure of Firefox to a file. You can then copy this file to another machine and install the closure:

$ nix-store --import < firefox.closure

Any store paths in the closure that are already present in the target store are ignored. It is also possible to pipe the export into another command, e.g. to copy and install a closure directly to/on another machine:

$ nix-store --export $(nix-store -qR $(type -p firefox)) | bzip2 | \

ssh alice@itchy.example.org "bunzip2 | nix-store --import"

However, nix-copy-closure is generally more efficient because it only copies paths that are not already present in the target Nix store.

13.3. Serving a Nix store via SSH

You can tell Nix to automatically fetch needed binaries from a remote Nix store via SSH. For example, the following installs Firefox, automatically fetching any store paths in Firefox’s closure if they are available on the server avalon:

$ nix-env -i firefox --substituters ssh://alice@avalon

This works similar to the binary cache substituter that Nix usually uses, only using SSH instead of HTTP: if a store path P is needed, Nix will first check if it’s available in the Nix store on avalon. If not, it will fall back to using the binary cache substituter, and then to building from source.

Note: The SSH substituter currently does not allow you to enter an SSH passphrase interactively. Therefore, you should use ssh-add to load the decrypted private key into ssh-agent.

You can also copy the closure of some store path, without installing it into your profile, e.g.

$ nix-store -r /nix/store/m85bxg…-firefox-34.0.5 --substituters ssh://alice@avalon

This is essentially equivalent to doing

$ nix-copy-closure --from alice@avalon /nix/store/m85bxg…-firefox-34.0.5

You can use SSH’s forced command feature to set up a restricted user account for SSH substituter access, allowing read-only access to the local Nix store, but nothing more. For example, add the following lines to sshd_config to restrict the user nix-ssh:

Match User nix-ssh AllowAgentForwarding no AllowTcpForwarding no PermitTTY no PermitTunnel no X11Forwarding no ForceCommand nix-store --serve Match All

On NixOS, you can accomplish the same by adding the following to your configuration.nix:

nix.sshServe.enable = true; nix.sshServe.keys = [ "ssh-dss AAAAB3NzaC1k... bob@example.org" ];

where the latter line lists the public keys of users that are allowed to connect.

13.4. Serving a Nix store via AWS S3 or S3-compatible Service

Nix has built-in support for storing and fetching store paths from Amazon S3 and S3 compatible services. This uses the same binary cache mechanism that Nix usually uses to fetch prebuilt binaries from cache.nixos.org.

The following options can be specified as URL parameters to the S3 URL:

profile

The name of the AWS configuration profile to use. By default Nix will use the default profile.

region

The region of the S3 bucket. us–east-1 by default.

If your bucket is not in us–east-1, you should always explicitly specify the region parameter.

endpoint

The URL to your S3-compatible service, for when not using Amazon S3. Do not specify this value if you're using Amazon S3.

Note: This endpoint must support HTTPS and will use path-based addressing instead of virtual host based addressing.

scheme

The scheme used for S3 requests, https (default) or http. This option allows you to disable HTTPS for binary caches which don't support it.

Note: HTTPS should be used if the cache might contain sensitive information.

In this example we will use the bucket named example-nix-cache.

13.4.1. Anonymous Reads to your S3-compatible binary cache

If your binary cache is publicly accessible and does not require authentication, the simplest and easiest way to use Nix with your S3 compatible binary cache is to use the HTTP URL for that cache.

For AWS S3 the binary cache URL for example bucket will be exactly https://example-nix-cache.s3.amazonaws.com or s3://example-nix-cache. For S3 compatible binary caches, consult that cache's documentation.

Your bucket will need the following bucket policy:

{

"Id": "DirectReads",

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Sid": "AllowDirectReads",

"Action": [

"s3:GetObject",

"s3:GetBucketLocation"

],

"Effect": "Allow",

"Resource": [

"arn:aws:s3:::example-nix-cache",

"arn:aws:s3:::example-nix-cache/*"

],

"Principal": "*"

}

]

}

13.4.2. Authenticated Reads to your S3 binary cache

For AWS S3 the binary cache URL for example bucket will be exactly s3://example-nix-cache.

Nix will use the default credential provider chain for authenticating requests to Amazon S3.

Nix supports authenticated reads from Amazon S3 and S3 compatible binary caches.

Your bucket will need a bucket policy allowing the desired users to perform the s3:GetObject and s3:GetBucketLocation action on all objects in the bucket. The anonymous policy in Section 13.4.1, “Anonymous Reads to your S3-compatible binary cache” can be updated to have a restricted Principal to support this.

13.4.3. Authenticated Writes to your S3-compatible binary cache

Nix support fully supports writing to Amazon S3 and S3 compatible buckets. The binary cache URL for our example bucket will be s3://example-nix-cache.

Nix will use the default credential provider chain for authenticating requests to Amazon S3.

Your account will need the following IAM policy to upload to the cache:

{

"Version": "2012-10-17",

"Statement": [

{

"Sid": "UploadToCache",

"Effect": "Allow",

"Action": [

"s3:AbortMultipartUpload",

"s3:GetBucketLocation",

"s3:GetObject",

"s3:ListBucket",

"s3:ListBucketMultipartUploads",

"s3:ListMultipartUploadParts",

"s3:ListObjects",

"s3:PutObject"

],

"Resource": [

"arn:aws:s3:::example-nix-cache",

"arn:aws:s3:::example-nix-cache/*"

]

}

]

}

Example 13.1. Uploading with a specific credential profile for Amazon S3

nix copy --to 's3://example-nix-cache?profile=cache-upload®ion=eu-west-2' nixpkgs.hello

Example 13.2. Uploading to an S3-Compatible Binary Cache

nix copy --to 's3://example-nix-cache?profile=cache-upload&scheme=https&endpoint=minio.example.com' nixpkgs.hello

Part IV. Writing Nix Expressions

This chapter shows you how to write Nix expressions, which instruct Nix how to build packages. It starts with a simple example (a Nix expression for GNU Hello), and then moves on to a more in-depth look at the Nix expression language.

Note: This chapter is mostly about the Nix expression language. For more extensive information on adding packages to the Nix Packages collection (such as functions in the standard environment and coding conventions), please consult its manual.

Chapter 14. A Simple Nix Expression

This section shows how to add and test the GNU Hello package to the Nix Packages collection. Hello is a program that prints out the text “Hello, world!”.

To add a package to the Nix Packages collection, you generally need to do three things:

-

Write a Nix expression for the package. This is a file that describes all the inputs involved in building the package, such as dependencies, sources, and so on.

-

Write a builder. This is a shell script[2] that actually builds the package from the inputs.

-

Add the package to the file

pkgs/top-level/all-packages.nix. The Nix expression written in the first step is a function; it requires other packages in order to build it. In this step you put it all together, i.e., you call the function with the right arguments to build the actual package.

14.1. Expression Syntax

Example 14.1. Nix expression for GNU Hello (default.nix)

{ stdenv, fetchurl, perl }:

stdenv.mkDerivation {

name = "hello-2.1.1";

builder = ./builder.sh;

src = fetchurl {

url = ftp://ftp.nluug.nl/pub/gnu/hello/hello-2.1.1.tar.gz;

sha256 = "1md7jsfd8pa45z73bz1kszpp01yw6x5ljkjk2hx7wl800any6465";

};

inherit perl;

}

Example 14.1, “Nix expression for GNU Hello (default.nix)” shows a Nix expression for GNU Hello. It's actually already in the Nix Packages collection inpkgs/applications/misc/hello/ex-1/default.nix. It is customary to place each package in a separate directory and call the single Nix expression in that directory default.nix. The file has the following elements (referenced from the figure by number):

| This states that the expression is a function that expects to be called with three arguments: Nix functions generally have the form | |

| So we have to build a package. Building something from other stuff is called a derivation in Nix (as opposed to sources, which are built by humans instead of computers). We perform a derivation by calling | |

| The attribute | |

| The attribute | |

| The builder has to know what the sources of the package are. Here, the attribute Instead of | |

| Since the derivation requires Perl, we have to pass the value of the perl = perl; will do the trick: it binds an attribute |

14.2. Build Script

Example 14.2. Build script for GNU Hello (builder.sh)

source $stdenv/setup PATH=$perl/bin:$PATH tar xvfz $src cd hello-* ./configure --prefix=$out make make install

Example 14.2, “Build script for GNU Hello (builder.sh)” shows the builder referenced from Hello's Nix expression (stored in pkgs/applications/misc/hello/ex-1/builder.sh). The builder can actually be made a lot shorter by using the generic builder functions provided by stdenv, but here we write out the build steps to elucidate what a builder does. It performs the following steps:

| When Nix runs a builder, it initially completely clears the environment (except for the attributes declared in the derivation). For instance, the So the first step is to set up the environment. This is done by calling the | |

| Since Hello needs Perl, we have to make sure that Perl is in the | |

| Now we have to unpack the sources. The The whole build is performed in a temporary directory created in | |

| GNU Hello is a typical Autoconf-based package, so we first have to run its | |

| Finally we build Hello ( |

If you are wondering about the absence of error checking on the result of various commands called in the builder: this is because the shell script is evaluated with Bash's -e option, which causes the script to be aborted if any command fails without an error check.

14.3. Arguments and Variables

Example 14.3. Composing GNU Hello (all-packages.nix)

...

rec {

hello = import ../applications/misc/hello/ex-1 {

inherit fetchurl stdenv perl;

};

perl = import ../development/interpreters/perl {

inherit fetchurl stdenv;

};

fetchurl = import ../build-support/fetchurl {

inherit stdenv; ...

};

stdenv = ...;

}

The Nix expression in Example 14.1, “Nix expression for GNU Hello (default.nix)” is a function; it is missing some arguments that have to be filled in somewhere. In the Nix Packages collection this is done in the file pkgs/top-level/all-packages.nix, where all Nix expressions for packages are imported and called with the appropriate arguments. Example 14.3, “Composing GNU Hello (all-packages.nix)” shows some fragments of all-packages.nix.

| This file defines a set of attributes, all of which are concrete derivations (i.e., not functions). In fact, we define a mutually recursive set of attributes. That is, the attributes can refer to each other. This is precisely what we want since we want to “plug” the various packages into each other. | |

| Here we import the Nix expression for GNU Hello. The import operation just loads and returns the specified Nix expression. In fact, we could just have put the contents of Example 14.1, “Nix expression for GNU Hello ( Note that we refer to | |

| This is where the actual composition takes place. Here we call the function imported from The result of this function call is an actual derivation that can be built by Nix (since when we fill in the arguments of the function, what we get is its body, which is the call to NoteNixpkgs has a convenience function hello = callPackage ../applications/misc/hello/ex-1 { };

If necessary, you can set or override arguments: hello = callPackage ../applications/misc/hello/ex-1 { stdenv = myStdenv; };

| |

| Likewise, we have to instantiate Perl, |

14.4. Building and Testing

You can now try to build Hello. Of course, you could do nix-env -i hello, but you may not want to install a possibly broken package just yet. The best way to test the package is by using the command nix-build, which builds a Nix expression and creates a symlink named result in the current directory:

$ nix-build -A hello

building path `/nix/store/632d2b22514d...-hello-2.1.1'

hello-2.1.1/

hello-2.1.1/intl/

hello-2.1.1/intl/ChangeLog

...

$ ls -l result

lrwxrwxrwx ... 2006-09-29 10:43 result -> /nix/store/632d2b22514d...-hello-2.1.1

$ ./result/bin/hello

Hello, world!

The -A option selects the hello attribute. This is faster than using the symbolic package name specified by the name attribute (which also happens to be hello) and is unambiguous (there can be multiple packages with the symbolic name hello, but there can be only one attribute in a set named hello).

nix-build registers the ./result symlink as a garbage collection root, so unless and until you delete the ./result symlink, the output of the build will be safely kept on your system. You can use nix-build’s -o switch to give the symlink another name.

Nix has a transactional semantics. Once a build finishes successfully, Nix makes a note of this in its database: it registers that the path denoted by out is now “valid”. If you try to build the derivation again, Nix will see that the path is already valid and finish immediately. If a build fails, either because it returns a non-zero exit code, because Nix or the builder are killed, or because the machine crashes, then the output paths will not be registered as valid. If you try to build the derivation again, Nix will remove the output paths if they exist (e.g., because the builder died half-way through make install) and try again. Note that there is no “negative caching”: Nix doesn't remember that a build failed, and so a failed build can always be repeated. This is because Nix cannot distinguish between permanent failures (e.g., a compiler error due to a syntax error in the source) and transient failures (e.g., a disk full condition).

Nix also performs locking. If you run multiple Nix builds simultaneously, and they try to build the same derivation, the first Nix instance that gets there will perform the build, while the others block (or perform other derivations if available) until the build finishes:

$ nix-build -A hello waiting for lock on `/nix/store/0h5b7hp8d4hqfrw8igvx97x1xawrjnac-hello-2.1.1x'

So it is always safe to run multiple instances of Nix in parallel (which isn’t the case with, say, make).

If you have a system with multiple CPUs, you may want to have Nix build different derivations in parallel (insofar as possible). Just pass the option -j , where NN is the maximum number of jobs to be run in parallel, or set. Typically this should be the number of CPUs.

14.5. Generic Builder Syntax

Recall from Example 14.2, “Build script for GNU Hello (builder.sh)” that the builder looked something like this:

PATH=$perl/bin:$PATH tar xvfz $src cd hello-* ./configure --prefix=$out make make install

The builders for almost all Unix packages look like this — set up some environment variables, unpack the sources, configure, build, and install. For this reason the standard environment provides some Bash functions that automate the build process. A builder using the generic build facilities in shown in Example 14.4, “Build script using the generic build functions”.

Example 14.4. Build script using the generic build functions

buildInputs="$perl" source $stdenv/setup genericBuild

| The | |

| The function | |

| The final step calls the shell function |

Discerning readers will note that the buildInputs could just as well have been set in the Nix expression, like this:

buildInputs = [ perl ];

The perl attribute can then be removed, and the builder becomes even shorter:

source $stdenv/setup genericBuild

In fact, mkDerivation provides a default builder that looks exactly like that, so it is actually possible to omit the builder for Hello entirely.

[2] In fact, it can be written in any language, but typically it's a bash shell script.

[3] Actually, it's initialised to /path-not-set to prevent Bash from setting it to a default value.

[4] How does it work? setup tries to source the file pkg/nix-support/setup-hookPERL5LIB environment variable to contain the lib/site_perl directories of all inputs.

Chapter 15. Nix Expression Language

The Nix expression language is a pure, lazy, functional language. Purity means that operations in the language don't have side-effects (for instance, there is no variable assignment). Laziness means that arguments to functions are evaluated only when they are needed. Functional means that functions are “normal” values that can be passed around and manipulated in interesting ways. The language is not a full-featured, general purpose language. Its main job is to describe packages, compositions of packages, and the variability within packages.

This section presents the various features of the language.

15.1. Values

Simple Values

Nix has the following basic data types:

-

Strings can be written in three ways.

The most common way is to enclose the string between double quotes, e.g.,

"foo bar". Strings can span multiple lines. The special characters"and\and the character sequence${must be escaped by prefixing them with a backslash (\). Newlines, carriage returns and tabs can be written as\n,\rand\t, respectively.You can include the result of an expression into a string by enclosing it in

${, a feature known as antiquotation. The enclosed expression must evaluate to something that can be coerced into a string (meaning that it must be a string, a path, or a derivation). For instance, rather than writing...}"--with-freetype2-library=" + freetype + "/lib"

(where

freetypeis a derivation), you can instead write the more natural"--with-freetype2-library=${freetype}/lib"The latter is automatically translated to the former. A more complicated example (from the Nix expression for Qt):

configureFlags = " -system-zlib -system-libpng -system-libjpeg ${if openglSupport then "-dlopen-opengl -L${mesa}/lib -I${mesa}/include -L${libXmu}/lib -I${libXmu}/include" else ""} ${if threadSupport then "-thread" else "-no-thread"} ";Note that Nix expressions and strings can be arbitrarily nested; in this case the outer string contains various antiquotations that themselves contain strings (e.g.,

"-thread"), some of which in turn contain expressions (e.g.,${mesa}).The second way to write string literals is as an indented string, which is enclosed between pairs of double single-quotes, like so:

'' This is the first line. This is the second line. This is the third line. ''This kind of string literal intelligently strips indentation from the start of each line. To be precise, it strips from each line a number of spaces equal to the minimal indentation of the string as a whole (disregarding the indentation of empty lines). For instance, the first and second line are indented two space, while the third line is indented four spaces. Thus, two spaces are stripped from each line, so the resulting string is

"This is the first line.\nThis is the second line.\n This is the third line.\n"

Note that the whitespace and newline following the opening

''is ignored if there is no non-whitespace text on the initial line.Antiquotation (

${) is supported in indented strings.expr}Since

${and''have special meaning in indented strings, you need a way to quote them.$can be escaped by prefixing it with''(that is, two single quotes), i.e.,''$.''can be escaped by prefixing it with', i.e.,'''.$removes any special meaning from the following$. Linefeed, carriage-return and tab characters can be written as''\n,''\r,''\t, and''\escapes any other character.Indented strings are primarily useful in that they allow multi-line string literals to follow the indentation of the enclosing Nix expression, and that less escaping is typically necessary for strings representing languages such as shell scripts and configuration files because

''is much less common than". Example:stdenv.mkDerivation {...postInstall = '' mkdir $out/bin $out/etc cp foo $out/bin echo "Hello World" > $out/etc/foo.conf ${if enableBar then "cp bar $out/bin" else ""} '';...}Finally, as a convenience, URIs as defined in appendix B of RFC 2396 can be written as is, without quotes. For instance, the string

"http://example.org/foo.tar.bz2"can also be written ashttp://example.org/foo.tar.bz2. -

Numbers, which can be integers (like

123) or floating point (like123.43or.27e13).Numbers are type-compatible: pure integer operations will always return integers, whereas any operation involving at least one floating point number will have a floating point number as a result.

-

Paths, e.g.,

/bin/shor./builder.sh. A path must contain at least one slash to be recognised as such; for instance,builder.shis not a path[5]. If the file name is relative, i.e., if it does not begin with a slash, it is made absolute at parse time relative to the directory of the Nix expression that contained it. For instance, if a Nix expression in/foo/bar/bla.nixrefers to../xyzzy/fnord.nix, the absolute path is/foo/xyzzy/fnord.nix.If the first component of a path is a

~, it is interpreted as if the rest of the path were relative to the user's home directory. e.g.~/foowould be equivalent to/home/edolstra/foofor a user whose home directory is/home/edolstra.Paths can also be specified between angle brackets, e.g.

<nixpkgs>. This means that the directories listed in the environment variableNIX_PATHwill be searched for the given file or directory name. -

Booleans with values

trueandfalse. -

The null value, denoted as

null.

Lists

Lists are formed by enclosing a whitespace-separated list of values between square brackets. For example,

[ 123 ./foo.nix "abc" (f { x = y; }) ]

defines a list of four elements, the last being the result of a call to the function f. Note that function calls have to be enclosed in parentheses. If they had been omitted, e.g.,

[ 123 ./foo.nix "abc" f { x = y; } ]

the result would be a list of five elements, the fourth one being a function and the fifth being a set.

Note that lists are only lazy in values, and they are strict in length.

Sets

Sets are really the core of the language, since ultimately the Nix language is all about creating derivations, which are really just sets of attributes to be passed to build scripts.

Sets are just a list of name/value pairs (called attributes) enclosed in curly brackets, where each value is an arbitrary expression terminated by a semicolon. For example:

{ x = 123;

text = "Hello";

y = f { bla = 456; };

}

This defines a set with attributes named x, text, y. The order of the attributes is irrelevant. An attribute name may only occur once.

Attributes can be selected from a set using the . operator. For instance,

{ a = "Foo"; b = "Bar"; }.a

evaluates to "Foo". It is possible to provide a default value in an attribute selection using the or keyword. For example,

{ a = "Foo"; b = "Bar"; }.c or "Xyzzy"

will evaluate to "Xyzzy" because there is no c attribute in the set.

You can use arbitrary double-quoted strings as attribute names:

{ "foo ${bar}" = 123; "nix-1.0" = 456; }."foo ${bar}"

This will evaluate to 123 (Assuming bar is antiquotable). In the case where an attribute name is just a single antiquotation, the quotes can be dropped:

{ foo = 123; }.${bar} or 456

This will evaluate to 123 if bar evaluates to "foo" when coerced to a string and 456 otherwise (again assuming bar is antiquotable).

In the special case where an attribute name inside of a set declaration evaluates to null (which is normally an error, as null is not antiquotable), that attribute is simply not added to the set:

{ ${if foo then "bar" else null} = true; }

This will evaluate to {} if foo evaluates to false.

A set that has a __functor attribute whose value is callable (i.e. is itself a function or a set with a __functor attribute whose value is callable) can be applied as if it were a function, with the set itself passed in first , e.g.,

let add = { __functor = self: x: x + self.x; };

inc = add // { x = 1; };

in inc 1

evaluates to 2. This can be used to attach metadata to a function without the caller needing to treat it specially, or to implement a form of object-oriented programming, for example.

15.2. Language Constructs

Recursive sets

Recursive sets are just normal sets, but the attributes can refer to each other. For example,

rec {

x = y;

y = 123;

}.x

evaluates to 123. Note that without rec the binding x = y; would refer to the variable y in the surrounding scope, if one exists, and would be invalid if no such variable exists. That is, in a normal (non-recursive) set, attributes are not added to the lexical scope; in a recursive set, they are.

Recursive sets of course introduce the danger of infinite recursion. For example,

rec {

x = y;

y = x;

}.x

does not terminate[6].

Let-expressions

A let-expression allows you define local variables for an expression. For instance,

let x = "foo"; y = "bar"; in x + y

evaluates to "foobar".

Inheriting attributes

When defining a set or in a let-expression it is often convenient to copy variables from the surrounding lexical scope (e.g., when you want to propagate attributes). This can be shortened using the inherit keyword. For instance,

let x = 123; in

{ inherit x;

y = 456;

}

is equivalent to

let x = 123; in

{ x = x;

y = 456;

}

and both evaluate to { x = 123; y = 456; }. (Note that this works because x is added to the lexical scope by the let construct.) It is also possible to inherit attributes from another set. For instance, in this fragment from all-packages.nix,

graphviz = (import ../tools/graphics/graphviz) {

inherit fetchurl stdenv libpng libjpeg expat x11 yacc;

inherit (xlibs) libXaw;

};

xlibs = {

libX11 = ...;

libXaw = ...;

...

}

libpng = ...;

libjpg = ...;

...

the set used in the function call to the function defined in ../tools/graphics/graphviz inherits a number of variables from the surrounding scope (fetchurl ... yacc), but also inheritslibXaw (the X Athena Widgets) from the xlibs (X11 client-side libraries) set.

Summarizing the fragment

... inherit x y z; inherit (src-set) a b c; ...

is equivalent to

... x = x; y = y; z = z; a = src-set.a; b = src-set.b; c = src-set.c; ...

when used while defining local variables in a let-expression or while defining a set.

Functions

Functions have the following form:

pattern:body

The pattern specifies what the argument of the function must look like, and binds variables in the body to (parts of) the argument. There are three kinds of patterns:

-

If a pattern is a single identifier, then the function matches any argument. Example:

let negate = x: !x; concat = x: y: x + y; in if negate true then concat "foo" "bar" else ""Note that

concatis a function that takes one argument and returns a function that takes another argument. This allows partial parameterisation (i.e., only filling some of the arguments of a function); e.g.,map (concat "foo") [ "bar" "bla" "abc" ]

evaluates to

[ "foobar" "foobla" "fooabc" ]. -

A set pattern of the form

{ name1, name2, …, nameN }matches a set containing the listed attributes, and binds the values of those attributes to variables in the function body. For example, the function{ x, y, z }: z + y + xcan only be called with a set containing exactly the attributes

x,yandz. No other attributes are allowed. If you want to allow additional arguments, you can use an ellipsis (...):{ x, y, z, ... }: z + y + xThis works on any set that contains at least the three named attributes.

It is possible to provide default values for attributes, in which case they are allowed to be missing. A default value is specified by writing

name?eeis an arbitrary expression. For example,{ x, y ? "foo", z ? "bar" }: z + y + xspecifies a function that only requires an attribute named

x, but optionally acceptsyandz. -

An

@-pattern provides a means of referring to the whole value being matched:args@{ x, y, z, ... }: z + y + x + args.abut can also be written as:

{ x, y, z, ... } @ args: z + y + x + args.aHere

argsis bound to the entire argument, which is further matched against the pattern{ x, y, z, ... }.@-pattern makes mainly sense with an ellipsis(...) as you can access attribute names asa, usingargs.a, which was given as an additional attribute to the function.

Note that functions do not have names. If you want to give them a name, you can bind them to an attribute, e.g.,

let concat = { x, y }: x + y;

in concat { x = "foo"; y = "bar"; }

Conditionals

Conditionals look like this:

ife1thene2elsee3

where e1 is an expression that should evaluate to a Boolean value (true or false).

Assertions

Assertions are generally used to check that certain requirements on or between features and dependencies hold. They look like this:

asserte1;e2

where e1 is an expression that should evaluate to a Boolean value. If it evaluates to true, e2 is returned; otherwise expression evaluation is aborted and a backtrace is printed.

Example 15.1. Nix expression for Subversion

{ localServer ? false

, httpServer ? false

, sslSupport ? false

, pythonBindings ? false

, javaSwigBindings ? false

, javahlBindings ? false

, stdenv, fetchurl

, openssl ? null, httpd ? null, db4 ? null, expat, swig ? null, j2sdk ? null

}:

assert localServer -> db4 != null;

assert httpServer -> httpd != null && httpd.expat == expat;

assert sslSupport -> openssl != null && (httpServer -> httpd.openssl == openssl);

assert pythonBindings -> swig != null && swig.pythonSupport;

assert javaSwigBindings -> swig != null && swig.javaSupport;

assert javahlBindings -> j2sdk != null;

stdenv.mkDerivation {

name = "subversion-1.1.1";

...

openssl = if sslSupport then openssl else null;

...

}

Example 15.1, “Nix expression for Subversion” show how assertions are used in the Nix expression for Subversion.

| This assertion states that if Subversion is to have support for local repositories, then Berkeley DB is needed. So if the Subversion function is called with the | |

| This is a more subtle condition: if Subversion is built with Apache ( | |

| This assertion says that in order for Subversion to have SSL support (so that it can access | |

| The conditional here is not really related to assertions, but is worth pointing out: it ensures that if SSL support is disabled, then the Subversion derivation is not dependent on OpenSSL, even if a non- |

With-expressions

A with-expression,

withe1;e2

introduces the set e1 into the lexical scope of the expression e2. For instance,

let as = { x = "foo"; y = "bar"; };

in with as; x + y

evaluates to "foobar" since the with adds the x and y attributes of as to the lexical scope in the expression x + y. The most common use of with is in conjunction with the importfunction. E.g.,

with (import ./definitions.nix); ...

makes all attributes defined in the file definitions.nix available as if they were defined locally in a let-expression.

The bindings introduced by with do not shadow bindings introduced by other means, e.g.

let a = 3; in with { a = 1; }; let a = 4; in with { a = 2; }; ...

establishes the same scope as

let a = 1; in let a = 2; in let a = 3; in let a = 4; in ...

Comments

Comments can be single-line, started with a # character, or inline/multi-line, enclosed within /* ... */.

15.3. Operators

Table 15.1, “Operators” lists the operators in the Nix expression language, in order of precedence (from strongest to weakest binding).

Table 15.1. Operators

| Syntax | Associativity | Description |

|---|---|---|

e . attrpath [ or def ] | none | Select attribute denoted by the attribute path attrpath from set e. (An attribute path is a dot-separated list of attribute names.) If the attribute doesn’t exist, return def if provided, otherwise abort evaluation. |

e1 e2 | left | Call function e1 with argument e2. |

- e | none | Arithmetic negation. |

e ? attrpath | none | Test whether set e contains the attribute denoted by attrpath; return true or false. |

e1 ++ e2 | right | List concatenation. |

e1 * e2, e1 / e2 | left | Arithmetic multiplication and division. |

e1 + e2, e1 - e2 | left | Arithmetic addition and subtraction. String or path concatenation (only by +). |

! e | none | Boolean negation. |

e1 // e2 | right | Return a set consisting of the attributes in e1 and e2 (with the latter taking precedence over the former in case of equally named attributes). |

e1 < e2, e1 > e2, e1 <=e2, e1 >= e2 | none | Arithmetic comparison. |

e1 == e2, e1 != e2 | none | Equality and inequality. |