脑电数据处理过程中如何去除伪迹是很重要的一个步骤,伪迹的处理主要包括眼电、心电、肌肉点以及工频干扰。实际处理过程中通过滤波0.5-45赫兹的带通滤波器可以去除掉大部分的噪音,在我接触到的实际脑电数数据中心电的伪迹大多数还真不是很明显,去伪迹的时候眼电的伪迹相对更加明显一些。MNE库中也有很多去伪迹的方法,这里给大家介绍一种ICA的方式。查看了一些文章,ICA在脑电数据处理中应用的也比较普遍。

采用ICA的方式去除伪迹,主要的工作就是分辨出ICA成分中的伪迹,实际上在你做完ICA后如果伪迹明显,还是很容易看出来的。在MNE提供的例子中默认你是有眼电心电记录的,通过ICA后的主成分和记录伪迹的相关性来判断伪迹。但是在实际的处理过程中,有可能你没有伪迹的记录,如何判断伪迹成分呢?

不同类型的伪迹有着一定的特点:

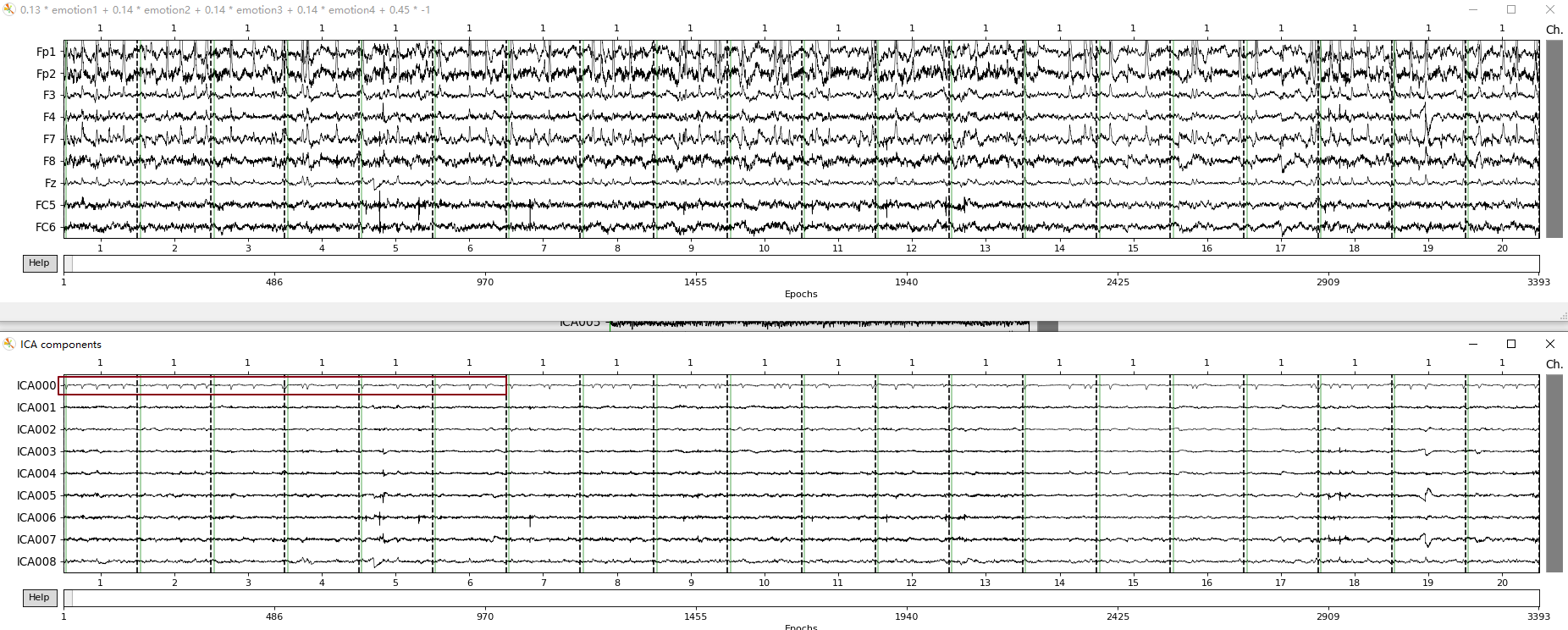

MNE中的例子:就算没有心电眼电的记录也基本能断定这里ICA000是眼电,ICA001是心电,你再和EOG061记录对比下,虽然幅值是反的,但形态基本一致。额外说一下如果是我处理的话,ICA002和ICA004也会去除,我认为这两个是干扰的噪声成分,可能是肌肉电也可能是噪声干扰,虽然滤波可以去除部分的频段,但难免有些噪声的频段是和脑电重合的啊。。。

实际的数据:红色圈出的我认为是眼电的伪迹

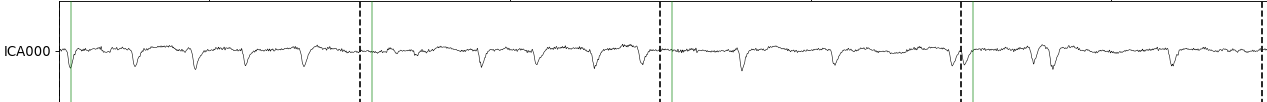

上面红色圈出部分的特写:眼电也就长这样了吧,呵呵。

MNE中提供的源码:改天写个这个代码的说明吧。

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

"""

.. _tut-artifact-ica:

Repairing artifacts with ICA

============================

This tutorial covers the basics of independent components analysis (ICA) and

shows how ICA can be used for artifact repair; an extended example illustrates

repair of ocular and heartbeat artifacts.

.. contents:: Page contents

:local:

:depth: 2

We begin as always by importing the necessary Python modules and loading some

:ref:`example data <sample-dataset>`. Because ICA can be computationally

intense, we'll also crop the data to 60 seconds; and to save ourselves from

repeatedly typing ``mne.preprocessing`` we'll directly import a few functions

and classes from that submodule:

"""

import os

import mne

from mne.preprocessing import (ICA, create_eog_epochs, create_ecg_epochs,

corrmap)

sample_data_folder = mne.datasets.sample.data_path()

sample_data_raw_file = os.path.join(sample_data_folder, 'MEG', 'sample',

'sample_audvis_raw.fif')

raw = mne.io.read_raw_fif(sample_data_raw_file)

raw.crop(tmax=60.)

###############################################################################

# .. note::

# Before applying ICA (or any artifact repair strategy), be sure to observe

# the artifacts in your data to make sure you choose the right repair tool.

# Sometimes the right tool is no tool at all — if the artifacts are small

# enough you may not even need to repair them to get good analysis results.

# See :ref:`tut-artifact-overview` for guidance on detecting and

# visualizing various types of artifact.

#

# What is ICA?

# ^^^^^^^^^^^^

#

# Independent components analysis (ICA) is a technique for estimating

# independent source signals from a set of recordings in which the source

# signals were mixed together in unknown ratios. A common example of this is

# the problem of `blind source separation`_: with 3 musical instruments playing

# in the same room, and 3 microphones recording the performance (each picking

# up all 3 instruments, but at varying levels), can you somehow "unmix" the

# signals recorded by the 3 microphones so that you end up with a separate

# "recording" isolating the sound of each instrument?

#

# It is not hard to see how this analogy applies to EEG/MEG analysis: there are

# many "microphones" (sensor channels) simultaneously recording many

# "instruments" (blinks, heartbeats, activity in different areas of the brain,

# muscular activity from jaw clenching or swallowing, etc). As long as these

# various source signals are `statistically independent`_ and non-gaussian, it

# is usually possible to separate the sources using ICA, and then re-construct

# the sensor signals after excluding the sources that are unwanted.

#

#

# ICA in MNE-Python

# ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

#

# .. sidebar:: ICA and dimensionality reduction

#

# If you want to perform ICA with *no* dimensionality reduction (other than

# the number of Independent Components (ICs) given in ``n_components``, and

# any subsequent exclusion of ICs you specify in ``ICA.exclude``), pass

# ``max_pca_components=None`` and ``n_pca_components=None`` (these are the

# default values).

#

# However, if you *do* want to reduce dimensionality, consider this

# example: if you have 300 sensor channels and you set

# ``max_pca_components=200``, ``n_components=50`` and

# ``n_pca_components=None``, then the PCA step yields 200 PCs, the first 50

# PCs are sent to the ICA algorithm (yielding 50 ICs), and during

# reconstruction :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.apply` will use the 50 ICs

# plus PCs number 51-200 (the full PCA residual). If instead you specify

# ``n_pca_components=120`` then :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.apply` will

# reconstruct using the 50 ICs plus the first 70 PCs in the PCA residual

# (numbers 51-120).

#

# **If you have previously been using EEGLAB**'s ``runica()`` and are

# looking for the equivalent of its ``'pca', n`` option to reduce

# dimensionality via PCA before the ICA step, set ``max_pca_components=n``,

# while leaving ``n_components`` and ``n_pca_components`` at their default

# (i.e., ``None``).

#

# MNE-Python implements three different ICA algorithms: ``fastica`` (the

# default), ``picard``, and ``infomax``. FastICA and Infomax are both in fairly

# widespread use; Picard is a newer (2017) algorithm that is expected to

# converge faster than FastICA and Infomax, and is more robust than other

# algorithms in cases where the sources are not completely independent, which

# typically happens with real EEG/MEG data. See [1]_ for more information.

#

# The ICA interface in MNE-Python is similar to the interface in

# `scikit-learn`_: some general parameters are specified when creating an

# :class:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA` object, then the

# :class:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA` object is fit to the data using its

# :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.fit` method. The results of the fitting are

# added to the :class:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA` object as attributes that end in

# an underscore (``_``), such as ``ica.mixing_matrix_`` and

# ``ica.unmixing_matrix_``. After fitting, the ICA component(s) that you want

# to remove must be chosen, and the ICA fit must then be applied to the

# :class:`~mne.io.Raw` or :class:`~mne.Epochs` object using the

# :class:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA` object's :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.apply`

# method.

#

# As is typically done with ICA, the data are first scaled to unit variance and

# whitened using principal components analysis (PCA) before performing the ICA

# decomposition. You can impose an optional dimensionality reduction at this

# step by specifying ``max_pca_components``. From the retained Principal

# Components (PCs), the first ``n_components`` are then passed to the ICA

# algorithm (``n_components`` may be an integer number of components to use, or

# a fraction of explained variance that used components should capture).

#

# After visualizing the Independent Components (ICs) and excluding any that

# capture artifacts you want to repair, the sensor signal can be reconstructed

# using the :class:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA` object's

# :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.apply` method. By default, signal

# reconstruction uses all of the ICs (less any ICs listed in ``ICA.exclude``)

# plus all of the PCs that were not included in the ICA decomposition (i.e.,

# the "PCA residual"). If you want to reduce the number of components used at

# the reconstruction stage, it is controlled by the ``n_pca_components``

# parameter (which will in turn reduce the rank of your data; by default

# ``n_pca_components = max_pca_components`` resulting in no additional

# dimensionality reduction). The fitting and reconstruction procedures and the

# parameters that control dimensionality at various stages are summarized in

# the diagram below:

#

# .. graphviz:: ../../_static/diagrams/ica.dot

# :alt: Diagram of ICA procedure in MNE-Python

# :align: left

#

# See the Notes section of the :class:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA` documentation

# for further details. Next we'll walk through an extended example that

# illustrates each of these steps in greater detail.

#

# Example: EOG and ECG artifact repair

# ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

#

# Visualizing the artifacts

# ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

#

# Let's begin by visualizing the artifacts that we want to repair. In this

# dataset they are big enough to see easily in the raw data:

# pick some channels that clearly show heartbeats and blinks

regexp = r'(MEG [12][45][123]1|EEG 00.)'

artifact_picks = mne.pick_channels_regexp(raw.ch_names, regexp=regexp)

raw.plot(order=artifact_picks, n_channels=len(artifact_picks))

###############################################################################

# We can get a summary of how the ocular artifact manifests across each channel

# type using :func:`~mne.preprocessing.create_eog_epochs` like we did in the

# :ref:`tut-artifact-overview` tutorial:

eog_evoked = create_eog_epochs(raw).average()

eog_evoked.apply_baseline(baseline=(None, -0.2))

eog_evoked.plot_joint()

###############################################################################

# Now we'll do the same for the heartbeat artifacts, using

# :func:`~mne.preprocessing.create_ecg_epochs`:

ecg_evoked = create_ecg_epochs(raw).average()

ecg_evoked.apply_baseline(baseline=(None, -0.2))

ecg_evoked.plot_joint()

###############################################################################

# Filtering to remove slow drifts

# ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

#

# Before we run the ICA, an important step is filtering the data to remove

# low-frequency drifts, which can negatively affect the quality of the ICA fit.

# The slow drifts are problematic because they reduce the independence of the

# assumed-to-be-independent sources (e.g., during a slow upward drift, the

# neural, heartbeat, blink, and other muscular sources will all tend to have

# higher values), making it harder for the algorithm to find an accurate

# solution. A high-pass filter with 1 Hz cutoff frequency is recommended.

# However, because filtering is a linear operation, the ICA solution found from

# the filtered signal can be applied to the unfiltered signal (see [2]_ for

# more information), so we'll keep a copy of the unfiltered

# :class:`~mne.io.Raw` object around so we can apply the ICA solution to it

# later.

filt_raw = raw.copy()

filt_raw.load_data().filter(l_freq=1., h_freq=None)

###############################################################################

# Fitting and plotting the ICA solution

# ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

#

# .. sidebar:: Ignoring the time domain

#

# The ICA algorithms implemented in MNE-Python find patterns across

# channels, but ignore the time domain. This means you can compute ICA on

# discontinuous :class:`~mne.Epochs` or :class:`~mne.Evoked` objects (not

# just continuous :class:`~mne.io.Raw` objects), or only use every Nth

# sample by passing the ``decim`` parameter to ``ICA.fit()``.

#

# Now we're ready to set up and fit the ICA. Since we know (from observing our

# raw data) that the EOG and ECG artifacts are fairly strong, we would expect

# those artifacts to be captured in the first few dimensions of the PCA

# decomposition that happens before the ICA. Therefore, we probably don't need

# a huge number of components to do a good job of isolating our artifacts

# (though it is usually preferable to include more components for a more

# accurate solution). As a first guess, we'll run ICA with ``n_components=15``

# (use only the first 15 PCA components to compute the ICA decomposition) — a

# very small number given that our data has over 300 channels, but with the

# advantage that it will run quickly and we will able to tell easily whether it

# worked or not (because we already know what the EOG / ECG artifacts should

# look like).

#

# ICA fitting is not deterministic (e.g., the components may get a sign

# flip on different runs, or may not always be returned in the same order), so

# we'll also specify a `random seed`_ so that we get identical results each

# time this tutorial is built by our web servers.

ica = ICA(n_components=15, random_state=97)

ica.fit(filt_raw)

###############################################################################

# Some optional parameters that we could have passed to the

# :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.fit` method include ``decim`` (to use only

# every Nth sample in computing the ICs, which can yield a considerable

# speed-up) and ``reject`` (for providing a rejection dictionary for maximum

# acceptable peak-to-peak amplitudes for each channel type, just like we used

# when creating epoched data in the :ref:`tut-overview` tutorial).

#

# Now we can examine the ICs to see what they captured.

# :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.plot_sources` will show the time series of the

# ICs. Note that in our call to :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.plot_sources` we

# can use the original, unfiltered :class:`~mne.io.Raw` object:

raw.load_data()

ica.plot_sources(raw)

###############################################################################

# Here we can pretty clearly see that the first component (``ICA000``) captures

# the EOG signal quite well, and the second component (``ICA001``) looks a lot

# like `a heartbeat <qrs_>`_ (for more info on visually identifying Independent

# Components, `this EEGLAB tutorial`_ is a good resource). We can also

# visualize the scalp field distribution of each component using

# :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.plot_components`. These are interpolated based

# on the values in the ICA unmixing matrix:

# sphinx_gallery_thumbnail_number = 9

ica.plot_components()

###############################################################################

# .. note::

#

# :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.plot_components` (which plots the scalp

# field topographies for each component) has an optional ``inst`` parameter

# that takes an instance of :class:`~mne.io.Raw` or :class:`~mne.Epochs`.

# Passing ``inst`` makes the scalp topographies interactive: clicking one

# will bring up a diagnostic :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.plot_properties`

# window (see below) for that component.

#

# In the plots above it's fairly obvious which ICs are capturing our EOG and

# ECG artifacts, but there are additional ways visualize them anyway just to

# be sure. First, we can plot an overlay of the original signal against the

# reconstructed signal with the artifactual ICs excluded, using

# :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.plot_overlay`:

# blinks

ica.plot_overlay(raw, exclude=[0], picks='eeg')

# heartbeats

ica.plot_overlay(raw, exclude=[1], picks='mag')

###############################################################################

# We can also plot some diagnostics of each IC using

# :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.plot_properties`:

ica.plot_properties(raw, picks=[0, 1])

###############################################################################

# In the remaining sections, we'll look at different ways of choosing which ICs

# to exclude prior to reconstructing the sensor signals.

#

#

# Selecting ICA components manually

# ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

#

# Once we're certain which components we want to exclude, we can specify that

# manually by setting the ``ica.exclude`` attribute. Similar to marking bad

# channels, merely setting ``ica.exclude`` doesn't do anything immediately (it

# just adds the excluded ICs to a list that will get used later when it's

# needed). Once the exclusions have been set, ICA methods like

# :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.plot_overlay` will exclude those component(s)

# even if no ``exclude`` parameter is passed, and the list of excluded

# components will be preserved when using :meth:`mne.preprocessing.ICA.save`

# and :func:`mne.preprocessing.read_ica`.

ica.exclude = [0, 1] # indices chosen based on various plots above

###############################################################################

# Now that the exclusions have been set, we can reconstruct the sensor signals

# with artifacts removed using the :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.apply` method

# (remember, we're applying the ICA solution from the *filtered* data to the

# original *unfiltered* signal). Plotting the original raw data alongside the

# reconstructed data shows that the heartbeat and blink artifacts are repaired.

# ica.apply() changes the Raw object in-place, so let's make a copy first:

reconst_raw = raw.copy()

ica.apply(reconst_raw)

raw.plot(order=artifact_picks, n_channels=len(artifact_picks))

reconst_raw.plot(order=artifact_picks, n_channels=len(artifact_picks))

del reconst_raw

###############################################################################

# Using an EOG channel to select ICA components

# ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

#

# It may have seemed easy to review the plots and manually select which ICs to

# exclude, but when processing dozens or hundreds of subjects this can become

# a tedious, rate-limiting step in the analysis pipeline. One alternative is to

# use dedicated EOG or ECG sensors as a "pattern" to check the ICs against, and

# automatically mark for exclusion any ICs that match the EOG/ECG pattern. Here

# we'll use :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.find_bads_eog` to automatically find

# the ICs that best match the EOG signal, then use

# :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.plot_scores` along with our other plotting

# functions to see which ICs it picked. We'll start by resetting

# ``ica.exclude`` back to an empty list:

ica.exclude = []

# find which ICs match the EOG pattern

eog_indices, eog_scores = ica.find_bads_eog(raw)

ica.exclude = eog_indices

# barplot of ICA component "EOG match" scores

ica.plot_scores(eog_scores)

# plot diagnostics

ica.plot_properties(raw, picks=eog_indices)

# plot ICs applied to raw data, with EOG matches highlighted

ica.plot_sources(raw)

# plot ICs applied to the averaged EOG epochs, with EOG matches highlighted

ica.plot_sources(eog_evoked)

###############################################################################

# Note that above we used :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.plot_sources` on both

# the original :class:`~mne.io.Raw` instance and also on an

# :class:`~mne.Evoked` instance of the extracted EOG artifacts. This can be

# another way to confirm that :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.find_bads_eog` has

# identified the correct components.

#

#

# Using a simulated channel to select ICA components

# ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

#

# If you don't have an EOG channel,

# :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.find_bads_eog` has a ``ch_name`` parameter that

# you can use as a proxy for EOG. You can use a single channel, or create a

# bipolar reference from frontal EEG sensors and use that as virtual EOG

# channel. This carries a risk however: you must hope that the frontal EEG

# channels only reflect EOG and not brain dynamics in the prefrontal cortex (or

# you must not care about those prefrontal signals).

#

# For ECG, it is easier: :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.find_bads_ecg` can use

# cross-channel averaging of magnetometer or gradiometer channels to construct

# a virtual ECG channel, so if you have MEG channels it is usually not

# necessary to pass a specific channel name.

# :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.find_bads_ecg` also has two options for its

# ``method`` parameter: ``'ctps'`` (cross-trial phase statistics [3]_) and

# ``'correlation'`` (Pearson correlation between data and ECG channel).

ica.exclude = []

# find which ICs match the ECG pattern

ecg_indices, ecg_scores = ica.find_bads_ecg(raw, method='correlation')

ica.exclude = ecg_indices

# barplot of ICA component "ECG match" scores

ica.plot_scores(ecg_scores)

# plot diagnostics

ica.plot_properties(raw, picks=ecg_indices)

# plot ICs applied to raw data, with ECG matches highlighted

ica.plot_sources(raw)

# plot ICs applied to the averaged ECG epochs, with ECG matches highlighted

ica.plot_sources(ecg_evoked)

###############################################################################

# The last of these plots is especially useful: it shows us that the heartbeat

# artifact is coming through on *two* ICs, and we've only caught one of them.

# In fact, if we look closely at the output of

# :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.plot_sources` (online, you can right-click →

# "view image" to zoom in), it looks like ``ICA014`` has a weak periodic

# component that is in-phase with ``ICA001``. It might be worthwhile to re-run

# the ICA with more components to see if that second heartbeat artifact

# resolves out a little better:

# refit the ICA with 30 components this time

new_ica = ICA(n_components=30, random_state=97)

new_ica.fit(filt_raw)

# find which ICs match the ECG pattern

ecg_indices, ecg_scores = new_ica.find_bads_ecg(raw, method='correlation')

new_ica.exclude = ecg_indices

# barplot of ICA component "ECG match" scores

new_ica.plot_scores(ecg_scores)

# plot diagnostics

new_ica.plot_properties(raw, picks=ecg_indices)

# plot ICs applied to raw data, with ECG matches highlighted

new_ica.plot_sources(raw)

# plot ICs applied to the averaged ECG epochs, with ECG matches highlighted

new_ica.plot_sources(ecg_evoked)

###############################################################################

# Much better! Now we've captured both ICs that are reflecting the heartbeat

# artifact (and as a result, we got two diagnostic plots: one for each IC that

# reflects the heartbeat). This demonstrates the value of checking the results

# of automated approaches like :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.find_bads_ecg`

# before accepting them.

# clean up memory before moving on

del raw, filt_raw, ica, new_ica

###############################################################################

# Selecting ICA components using template matching

# ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

#

# When dealing with multiple subjects, it is also possible to manually select

# an IC for exclusion on one subject, and then use that component as a

# *template* for selecting which ICs to exclude from other subjects' data,

# using :func:`mne.preprocessing.corrmap` [4]_. The idea behind

# :func:`~mne.preprocessing.corrmap` is that the artifact patterns are similar

# enough across subjects that corresponding ICs can be identified by

# correlating the ICs from each ICA solution with a common template, and

# picking the ICs with the highest correlation strength.

# :func:`~mne.preprocessing.corrmap` takes a list of ICA solutions, and a

# ``template`` parameter that specifies which ICA object and which component

# within it to use as a template.

#

# Since our sample dataset only contains data from one subject, we'll use a

# different dataset with multiple subjects: the EEGBCI dataset [5]_ [6]_. The

# dataset has 109 subjects, we'll just download one run (a left/right hand

# movement task) from each of the first 4 subjects:

mapping = {

'Fc5.': 'FC5', 'Fc3.': 'FC3', 'Fc1.': 'FC1', 'Fcz.': 'FCz', 'Fc2.': 'FC2',

'Fc4.': 'FC4', 'Fc6.': 'FC6', 'C5..': 'C5', 'C3..': 'C3', 'C1..': 'C1',

'Cz..': 'Cz', 'C2..': 'C2', 'C4..': 'C4', 'C6..': 'C6', 'Cp5.': 'CP5',

'Cp3.': 'CP3', 'Cp1.': 'CP1', 'Cpz.': 'CPz', 'Cp2.': 'CP2', 'Cp4.': 'CP4',

'Cp6.': 'CP6', 'Fp1.': 'Fp1', 'Fpz.': 'Fpz', 'Fp2.': 'Fp2', 'Af7.': 'AF7',

'Af3.': 'AF3', 'Afz.': 'AFz', 'Af4.': 'AF4', 'Af8.': 'AF8', 'F7..': 'F7',

'F5..': 'F5', 'F3..': 'F3', 'F1..': 'F1', 'Fz..': 'Fz', 'F2..': 'F2',

'F4..': 'F4', 'F6..': 'F6', 'F8..': 'F8', 'Ft7.': 'FT7', 'Ft8.': 'FT8',

'T7..': 'T7', 'T8..': 'T8', 'T9..': 'T9', 'T10.': 'T10', 'Tp7.': 'TP7',

'Tp8.': 'TP8', 'P7..': 'P7', 'P5..': 'P5', 'P3..': 'P3', 'P1..': 'P1',

'Pz..': 'Pz', 'P2..': 'P2', 'P4..': 'P4', 'P6..': 'P6', 'P8..': 'P8',

'Po7.': 'PO7', 'Po3.': 'PO3', 'Poz.': 'POz', 'Po4.': 'PO4', 'Po8.': 'PO8',

'O1..': 'O1', 'Oz..': 'Oz', 'O2..': 'O2', 'Iz..': 'Iz'

}

raws = list()

icas = list()

for subj in range(4):

# EEGBCI subjects are 1-indexed; run 3 is a left/right hand movement task

fname = mne.datasets.eegbci.load_data(subj + 1, runs=[3])[0]

raw = mne.io.read_raw_edf(fname)

# remove trailing `.` from channel names so we can set montage

raw.rename_channels(mapping)

raw.set_montage('standard_1005')

# fit ICA

ica = ICA(n_components=30, random_state=97)

ica.fit(raw)

raws.append(raw)

icas.append(ica)

###############################################################################

# Now let's run :func:`~mne.preprocessing.corrmap`:

# use the first subject as template; use Fpz as proxy for EOG

raw = raws[0]

ica = icas[0]

eog_inds, eog_scores = ica.find_bads_eog(raw, ch_name='Fpz')

corrmap(icas, template=(0, eog_inds[0]))

###############################################################################

# The first figure shows the template map, while the second figure shows all

# the maps that were considered a "match" for the template (including the

# template itself). There were only three matches from the four subjects;

# notice the output message ``No maps selected for subject(s) 1, consider a

# more liberal threshold``. By default the threshold is set automatically by

# trying several values; here it may have chosen a threshold that is too high.

# Let's take a look at the ICA sources for each subject:

for index, (ica, raw) in enumerate(zip(icas, raws)):

fig = ica.plot_sources(raw)

fig.suptitle('Subject {}'.format(index))

###############################################################################

# Notice that subject 1 *does* seem to have an IC that looks like it reflects

# blink artifacts (component ``ICA000``). Notice also that subject 3 appears to

# have *two* components that are reflecting ocular artifacts (``ICA000`` and

# ``ICA002``), but only one was caught by :func:`~mne.preprocessing.corrmap`.

# Let's try setting the threshold manually:

corrmap(icas, template=(0, eog_inds[0]), threshold=0.9)

###############################################################################

# Now we get the message ``At least 1 IC detected for each subject`` (which is

# good). At this point we'll re-run :func:`~mne.preprocessing.corrmap` with

# parameters ``label=blink, show=False`` to *label* the ICs from each subject

# that capture the blink artifacts (without plotting them again).

corrmap(icas, template=(0, eog_inds[0]), threshold=0.9, label='blink',

plot=False)

print([ica.labels_ for ica in icas])

###############################################################################

# Notice that the first subject has 3 different labels for the IC at index 0:

# "eog/0/Fpz", "eog", and "blink". The first two were added by

# :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.find_bads_eog`; the "blink" label was added by

# the last call to :func:`~mne.preprocessing.corrmap`. Notice also that each

# subject has at least one IC index labelled "blink", and subject 3 has two

# components (0 and 2) labelled "blink" (consistent with the plot of IC sources

# above). The ``labels_`` attribute of :class:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA` objects

# can also be manually edited to annotate the ICs with custom labels. They also

# come in handy when plotting:

icas[3].plot_components(picks=icas[3].labels_['blink'])

icas[3].exclude = icas[3].labels_['blink']

icas[3].plot_sources(raws[3])

###############################################################################

# As a final note, it is possible to extract ICs numerically using the

# :meth:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA.get_components` method of

# :class:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA` objects. This will return a :class:`NumPy

# array <numpy.ndarray>` that can be passed to

# :func:`~mne.preprocessing.corrmap` instead of the :class:`tuple` of

# ``(subject_index, component_index)`` we passed before, and will yield the

# same result:

template_eog_component = icas[0].get_components()[:, eog_inds[0]]

corrmap(icas, template=template_eog_component, threshold=0.9)

print(template_eog_component)

###############################################################################

# An advantage of using this numerical representation of an IC to capture a

# particular artifact pattern is that it can be saved and used as a template

# for future template-matching tasks using :func:`~mne.preprocessing.corrmap`

# without having to load or recompute the ICA solution that yielded the

# template originally. Put another way, when the template is a NumPy array, the

# :class:`~mne.preprocessing.ICA` object containing the template does not need

# to be in the list of ICAs provided to :func:`~mne.preprocessing.corrmap`.

#

#

# References

# ^^^^^^^^^^

#

# .. [1] Ablin P, Cardoso J, Gramfort A (2018). Faster Independent Component

# Analysis by Preconditioning With Hessian Approximations. *IEEE

# Transactions on Signal Processing* 66:4040–4049.

# https://doi.org/10.1109/TSP.2018.2844203

#

# .. [2] Winkler I, Debener S, Müller K-R, Tangermann M (2015). On the

# influence of high-pass filtering on ICA-based artifact reduction in

# EEG-ERP. Proceedings of EMBC-2015, 4101–4105.

# https://doi.org/10.1109/EMBC.2015.7319296

#

# .. [3] Dammers J, Schiek M, Boers F, Silex C, Zvyagintsev M, Pietrzyk U,

# Mathiak K (2008). Integration of amplitude and phase statistics for

# complete artifact removal in independent components of neuromagnetic

# recordings. *IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering*

# 55(10):2353–2362. https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2008.926677

#

# .. [4] Viola FC, Thorne J, Edmonds B, Schneider T, Eichele T, Debener S

# (2009). Semi-automatic identification of independent components

# representing EEG artifact. *Clinical Neurophysiology* 120(5):868–877.

# https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2009.01.015

#

# .. [5] Schalk G, McFarland DJ, Hinterberger T, Birbaumer N, Wolpaw JR (2004).

# BCI2000: A General-Purpose Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) System.

# *IEEE Transactions on Biomedical Engineering* 51(6):1034-1043.

# https://doi.org/10.1109/TBME.2004.827072

#

# .. [6] Goldberger AL, Amaral LAN, Glass L, Hausdorff JM, Ivanov PCh, Mark RG,

# Mietus JE, Moody GB, Peng C-K, Stanley HE (2000). PhysioBank,

# PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet: Components of a New Research Resource

# for Complex Physiologic Signals. *Circulation* 101(23):e215-e220.

# https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.101.23.e215

#

#

# .. LINKS

#

# .. _`blind source separation`:

# https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Signal_separation

# .. _`statistically independent`:

# https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Independence_(probability_theory)

# .. _`scikit-learn`: https://scikit-learn.org

# .. _`random seed`: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Random_seed

# .. _`regular expression`: https://www.regular-expressions.info/

# .. _`qrs`: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/QRS_complex

# .. _`this EEGLAB tutorial`: https://labeling.ucsd.edu/tutorial/labels

4562

4562

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?