数字取证

When the term “push button forensics” was coined 10+ years ago, it was a sarcastic pejorative. A lot of forensic examiners resisted vendors’ efforts to automate the acquisition and analysis of digital data. They believed automation would make it harder to document, validate, and thus defend their science in a court of law.

当“ 按钮取证 ”一词在10多年前被提出时,它是讽刺性的贬义词。 许多法医检查员拒绝了供应商自动进行数字数据获取和分析的工作。 他们认为,自动化将使其难以记录,验证并因此在法院为自己的科学辩护。

That started to change as hard disk drives reached the 1TB range and the iPhone led the way for a new breed of smartphone. Not only were storage sizes increasing; the number of storage media — phones, gaming devices, external drives, USB sticks, etc. — being seized climbed, too. Forensic labs ended up with backlogs, some as severe as several months. That delayed investigations, which could impact criminal defendants’ right to a speedy trial.

随着硬盘驱动器达到1TB的范围,这种情况开始改变,iPhone引领了新型智能手机的发展。 存储容量不仅在增加,而且 被查封的存储媒体(电话,游戏设备,外部驱动器,USB记忆棒等)的数量也在攀升。 法医实验室最终积压下来,有些甚至长达数月之久。 这拖延了调查,可能会影响刑事被告的Swift审判权。

“The number of people available who can manually sort through the complex evidence isn’t keeping pace,” blogged David Kovar in late 2009 — the year the United States’ Great Recession tightened both public- and private-sector belts, limiting labs’ ability to hire and train more people.

“可手动分类复杂证据的人数并没有跟上步伐,”大卫·科瓦(David Kovar)在2009年末写道。雇用和培训更多的人。

At the time, Kovar and Dark Reading’s John Sawyer saw opportunity. Forensic practitioners could employ a two-tier system already in use in law and private investigation practices: give the automated work to junior associates, leaving the analysis and interpretation to the senior examiners.

当时,科瓦和暗读的约翰·索耶(John Sawyer)看到了机会。 法务从业人员可以采用法律和私人调查实践中已经使用的两层系统 :将自动化工作交给初级律师,而将分析和解释留给高级审查员。

Yet other factors were in play. “Doing more with less,” a recession-era theme, would persist throughout the next decade — even as technology trends accelerated. By now most examiners agree that “push-button forensics” has delivered on its promises of efficiency, but whether it’s preserved scientific principles is another question entirely.

还有其他因素在起作用。 经济衰退时期的主题是“事半功倍”,即使技术趋势在加速发展。 到目前为止,大多数审查员都同意“按钮式取证”已实现了其对效率的承诺,但是,是否保留科学原理完全是另一个问题。

“最低可行”的法证 (“Minimally viable” forensic evidence)

On the heels of the Great Recession, more than $4 billion in federal stimulus funding had been allocated to help state and local law enforcement agencies recover from recession-related funding crises.

在大萧条之后, 联邦拨款超过40亿美元的刺激资金用于帮助各州和地方执法机构从与衰退有关的资金危机中恢复过来。

At the same time, though, technology was making data acquisition more complicated. Cell phones were becoming increasingly common as evidence sources, but had some unique features that meant standard computer forensic practices no longer worked.

但是,与此同时,技术使数据采集更加复杂。 手机作为证据来源变得越来越普遍,但是手机具有一些独特的功能,这意味着标准的计算机取证实践不再起作用。

In particular, forensic examiners were used to attaching hardware write-blockers to hard drives, to protect evidentiary integrity as evidence was copied or “imaged” bit for bit from the evidence hard drive to a fresh drive used for analysis.

特别是,取证检查员习惯将硬件写阻止器连接到硬盘驱动器,以保护证据完整性,因为证据从证据硬盘驱动器到用于分析的新驱动器一点一点地被复制或“成像”。

However, these write-blockers physically couldn’t work on cell phones, and no phone-specific equivalent existed. The forensic methods used to acquire their data had to adapt.

但是,这些写阻止程序实际上无法在手机上运行,并且不存在特定于手机的等效功能 。 用于获取其数据的取证方法必须适应。

Forensic examiners learned that many of the tools associated with cell phone repair, could be adapted to use in the forensic lab. For example, some examiners would come to use tools like “flasher boxes” — used by retailers to overwrite or “flash” a device’s flash memory in order to upgrade it or change service providers — to acquire a device’s physical image.

法医检查人员了解到,与手机维修相关的许多工具都可以在法医实验室中使用。 例如,一些检查员会使用“闪光盒”之类的工具来获取设备的物理图像,“闪光盒”被零售商用来覆盖或“刷新”设备的闪存以升级或更改服务提供商。

That allowed them to access deleted data, but could also destroy evidence. Still, in high-profile or very serious cases where it was a last resort, the risk was deemed acceptable as long as the actions and their changes were well documented, and examiners tested the actions on devices of the same make and model to ensure user data wouldn’t be changed or deleted.

这使他们可以访问已删除的数据,但也可能破坏证据 。 尽管如此,在万不得已的引人注目的或非常严重的情况下,只要对行为及其更改进行了充分记录,风险就可以接受,并且检查人员在相同品牌和型号的设备上测试了行为,以确保用户数据不会被更改或删除。

Ultimately, tools like Cellebrite’s would come to adapt flasher-box-like methodology. The company had gotten its start in the forensic industry by repurposing its retail data-transfer machines to make read-only copies of evidentiary data, relying on a device’s application programming interface (API) to obtain live user data. (Cellebrite white paper, “What Happens When You Push That Button? Explaining Cellebrite UFED Data Extraction Processes,” 2014)

最终,像Cellebrite的工具将适应闪光盒式方法。 该公司通过重新利用其零售数据传输机来制作证据数据的只读副本,并依靠设备的应用程序编程接口(API)来获取实时用户数据,从而开始了法医行业的发展。 (Cellebrite白皮书,“按下该按钮时会发生什么?解释Cellebrite UFED数据提取过程,” 2014年)

When it came to acquiring physical evidence, Cellebrite’s case, custom “boot loaders” — the small pieces of code that a flasher box relied on to overwrite memory — were adapted for a forensic context. This allowed direct, read-only access to flash memory and thus, to deleted data. (Cellebrite, “What Happens When You Push That Button?”)

在获取物理证据时,Cellebrite的案例中,定制的“引导加载程序”(即闪光盒用来覆盖内存的一小段代码)适用于法医环境。 这允许直接,只读访问闪存,从而访问删除的数据。 (Cellebrite,“按下该按钮时会发生什么?”)

That made the otherwise time-consuming flasher-box methods increasingly obsolete. At the same time, mobile devices were giving way to “smart” devices whose SQLite databases, similar to the file systems many examiners were already familiar with from computers, were easier for tools to parse.

这使得原本耗时的闪光灯盒方法变得过时了。 同时,移动设备被“智能”设备所取代 ,这些设备SQLite数据库类似于许多审查员已经从计算机熟悉的文件系统,工具更易于解析。

By that time, more commercial and free, open-source forensic tools had entered the market, and it became easier to validate one tool’s results with another’s. Yet according to digital forensics expert Brett Shavers, many law enforcement supervisors at the time didn’t understand why more than one tool should be necessary. As long as the tool acquired evidence, the reasoning went, why spend money that could be put towards other needed resources — patrol vehicles, say, or ballistic armor?

到那时,更多的商业和免费的开源法证工具已经进入市场,并且变得更容易与另一工具验证结果。 然而,根据数字取证专家Brett Shavers的说法,当时许多执法主管不理解为什么需要不止一种工具的原因。 只要工具获得了证据,推理就开始了,为什么要花本可以用于其他所需资源的资金-例如巡逻车或弹道装甲?

Furthermore, as devices themselves continued to proliferate, many labs simply could not make time for validation or in some cases, even investigation. Shavers says personnel were another challenge because the requirement for only sworn examiners to handle certain types of evidence meant that law enforcement agencies, relative to private companies, had a much smaller pool of candidates to draw from. From there, says Shavers, eligibility based on seniority or other assignments rendered that pool even smaller.

此外,随着设备本身的不断扩散,许多实验室根本无法腾出时间进行验证,甚至在某些情况下甚至无法进行调查 。 剃须刀说,人员是另一个挑战,因为只有宣誓的审查员才能处理某些类型的证据,这意味着与私营公司相比,执法机构的应聘者人数要少得多。 Shavers说,从那里开始,基于资历或其他任务的资格使该池变得更小。

In the private sector, it was a different matter. Digital forensics was being used to support both electronic discovery and cyber incident response. These better funded organizations did end up implementing the two-tier system envisioned by Kovar and Sawyer.

在私营部门,这是另一回事。 数字取证被用于支持电子发现和网络事件响应。 这些资金充裕的组织最终实施了Kovar和Sawyer设想的两层系统。

It’s a model, Kovar says now, that has been implemented throughout the private sector — notably on incident response teams. Junior-level staff monitor and triage alerts, bumping more serious ones up to senior-level responders.

Kovar现在说,这是一个模型,已在整个私营部门中实施,尤其是在事件响应团队中。 初级人员监视和分类警报,将更严重的警报传递给高级响应者。

In contrast, while many law enforcement agencies by now have some in-house forensic analysis capacity, it doesn’t match what the private sector has. “The disparity in the level of capability is incredible due to how much agencies spend on tools, personnel, and training,” says Shavers.

相比之下,虽然目前许多执法机构具有一定的内部法证分析能力,但与私营部门的能力不符。 “由于代理机构在工具,人员和培训上的花费很大,因此能力水平上的差异令人难以置信,” Shavers说。

In his experience, even the two-tier lab environment can be complicated. “In some respects, this method works, but depends on the tool being used and the type of evidence being sought,” he explains. “‘Easy’ cases work, but there is a huge gray area between the ‘easy’ case and the ‘difficult’ case.”

以他的经验,即使是两层实验室环境也可能很复杂。 他解释说:“在某些方面,这种方法有效,但取决于所使用的工具和所需证据的类型。” “'简单'的案例行之有效,但是'简单'案例和'困难'案例之间存在巨大的灰色区域。”

“Field” tools like kiosks can help in this regard, Shavers adds, “where users can point and click to get a preliminary report; but… I have seen this be the final product rather than an [impetus] to do a more complete analysis.” In other words, push button forensics might have delivered in terms of efficiency, but not necessarily in terms of completeness.

Shavers补充说,信息亭等“现场”工具可以在这方面提供帮助,“用户可以点击并单击以获取初步报告; 但是……我认为这是最终产品,而不是[impetus]做更全面的分析。” 换句话说,按钮取证可能就效率而言而已,但不一定就完整性而言。

That’s significant when it comes to current forensic challenges. Encryption in particular has made it more difficult for examiners to access critical data. Either encrypted devices aren’t supported by forensic tools, or for lower level offenses, few teams can justify in-depth forensic examinations or trials, with prosecutors often opting for plea bargains instead.

对于当前的法证挑战,这非常重要。 尤其是加密,使审查员更难以访问关键数据。 法医工具不支持加密设备,或者对于较低级别的犯罪,很少有团队可以证明深入的法医检查或审判的合理性,而检察官通常会选择辩诉交易。

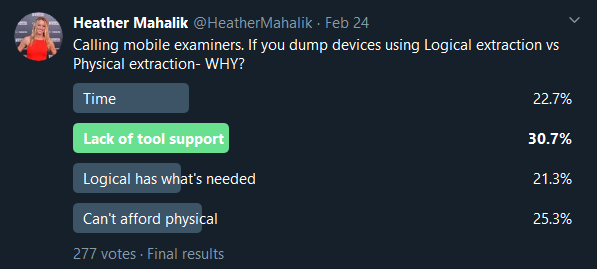

This is reflected in a recent Twitter poll run by SANS Senior Instructor and Cellebrite Senior Director of Digital Intelligence Heather Mahalik. Asked to vote on reasons for conducting logical versus physical extractions on mobile devices:

SANS高级讲师和Cellebrite数字情报高级主管Heather Mahalik进行的Twitter最新民意调查反映了这一点。 要求对在移动设备上进行逻辑提取与物理提取的原因进行投票:

- Nearly 31 percent of 277 respondents cited lack of tool support. 277位受访者中有近31%的受访者表示缺乏工具支持。

- Another 25 percent reflected that they “can’t afford” a physical examination. 另有25%的人反映他们“负担不起”身体检查。

- Close to 23 percent said they didn’t have the time. 接近23%的人说他们没有时间。

- Twenty-one percent said a logical extraction “has what’s needed.” 21%的人说逻辑上的提取“有需要”。

In other words, while forensic validation is as necessary as ever and continues to be championed in some quarters — notably the open source tool community — for many practical purposes, validation may be viewed as a “nice to have” relied upon only in high-profile trials.

换句话说,尽管鉴识验证是一如既往的必要,并且在某些方面(尤其是开放源代码工具社区)一直受到拥护,但出于许多实际目的,验证可能仅被视为一种“必须”,轮廓试验。

是否提供了按钮取证? (Has push button forensics delivered?)

Between high data volumes, more complicated methods, and few trained and experienced examiners, push-button tools have naturally held appeal. Yet Kovar’s blog post contained another insight: “Tool vendors have a vested interest in selling forensics and e-discovery tools that can be used by people without forensics experience and certifications.”

在高数据量,更复杂的方法以及训练有素和经验丰富的审查员之间,按钮式工具自然具有吸引力。 然而,Kovar的博客文章包含了另一种见解:“工具供应商对销售取证和电子发现工具有既得利益,这些取证和电子发现工具可以供未经取证经验和认证的人使用。”

To that end, his blog had been explicit in his assumptions: “push button forensics” had a place in labs where:

为此,他的博客明确地假设:“按钮取证”在实验室中占有一席之地:

- “The tools work as advertised, their behavior and results are well understood, and the process and results can be verified. “这些工具可以像宣传的那样工作,它们的行为和结果得到很好的理解,并且可以验证过程和结果。

- “The tools are verified internally. “这些工具已经过内部验证。

- “The use of the tools is supervised by experienced staff.” “该工具的使用由经验丰富的人员监督。”

Rather than implement the two-tier system, law enforcement has instead moved towards “democratizing” some digital forensics capabilities. At the time of this writing, multiple vendors sell “field forensics” tools that are used by investigators and patrol officers with little to no forensics experience. They may be certified to use the tool, or able to operate it in the same way they would speed-detection radar or a Breathalyzer.

执法部门没有实施两级系统,而是采取了“民主化”某些数字取证功能的措施。 在撰写本文时,多家供应商出售了“现场取证”工具,供调查人员和巡逻人员使用,这些工具几乎没有取证经验。 他们可能被证明可以使用该工具,或者能够以与速度检测雷达或呼吸分析仪相同的方式进行操作。

Those technologies, however, have standard validation processes in place, and they are relatively easy to implement. For example, Breathalyzer validation requires calibration to a known data set at least once per year. That’s because the underlying evidence doesn’t change. “[H]uman hair is human hair,” says Shavers. “The testing methods of human hair may change (i.e., improve), but the hair does not.”

但是,这些技术具有标准的验证过程,并且相对容易实现。 例如, 呼吸分析仪验证要求 每年至少 校准一次已知数据集。 那是因为基本证据没有改变。 “ [人类的头发就是人类的头发,” Shavers说。 “人类头发的测试方法可能会改变(即改善),但头发不会改变。”

Digital forensic tool validation is much more complicated. It’s highly dependent on the nature and type of data in question, the storage device, the operating system the device uses, and the software used to create, send, receive, store, and/or delete the data.

数字取证工具验证要复杂得多。 它高度取决于所讨论数据的性质和类型,存储设备,该设备使用的操作系统以及用于创建,发送,接收,存储和/或删除数据的软件。

Users have to validate not just the results, but also the manner in which they’re acquired — that different types of acquisitions will result in an expected set of data, and that the tool will interpret the data correctly.

用户不仅要验证结果,还要验证其获取方式—不同类型的获取将产生预期的数据集,并且该工具将正确地解释数据。

It’s a moving target when new acquisition methods are discovered yearly, operating system and app versions change, and new devices and apps come to market. Sawyer’s article in Dark Reading predicted this, though perhaps not in the way he envisioned when he wrote: “What concerns me is the forensic cases that occur more on the fringe where an attacker or suspect uses a system that isn’t supported by the [push button forensics] tool.”

当每年发现新的获取方法,更改操作系统和应用程序版本以及将新设备和应用程序推向市场时,这是一个移动的目标。 索耶(Sawyer)在《黑暗阅读》中的文章对此进行了预测,尽管可能与他写时所设想的方式不同:“令我担心的是,法医案件更多发生在边缘地区,攻击者或嫌疑人使用的系统不受[按钮取证]工具。”

In fact, tools routinely “break” owing to all the changes on modern digital devices, necessitating frequent releases throughout the year that might fix the problem, introduce new methodology, or refine what was already there.

实际上, 由于现代数字设备上的所有更改 ,工具通常会“崩溃”,需要在全年中频繁发布以解决问题,引入新方法或完善已经存在的工具。

That, says Shavers, gives rise to “a two-part problem of validating every tool with each improvement of each tool against the electronic evidence that changes in formats and operating systems. It’s like balancing two see-saws on each end of another see-saw.”

Shavers说,这引起了“两部分的问题,即根据格式和操作系统变化的电子证据来验证每个工具的每个改进。 就像在另一个跷跷板的两端平衡两个跷跷板一样。”

Shavers says as some tasks like triage become “democratized” and tools / methods themselves become more opaque, labs have no choice but to make the time for quality assurance. “Validation of tools will always be difficult until tools stop improving or the electronic evidence/devices stop changing,” he explains. “Good work means making sure your tools are in order; no different than an auto mechanic keeping the tools in the toolbox clean and serviceable.” That, he adds, may not be a revenue source for a private lab, but rather “a maintenance requirement that can impact revenue in either a positive or negative manner.”

剃须刀说,随着分类检查等任务变得“民主化”,工具/方法本身变得更加不透明,实验室别无选择,只能抽出时间来保证质量。 他解释说:“直到工具停止改进或电子证据/设备停止变化,对工具的验证总是很困难。” “做好工作意味着确保您的工具井然有序; 保持汽车工具箱中的工具清洁和可维修的汽车修理工无异。” 他补充说,这可能不是私人实验室的收入来源,而是“维护要求,可能以正面或负面的方式影响收入。”

Good validation practices impact accuracy in both public and private sectors. “There are no admissibility requirements in incident response,” Kovar says, “but a great deal of accuracy is still required.” For example, the inability to report whether customer social security numbers were exfiltrated could have severe regulatory repercussions, resulting in significant monetary damage.

良好的验证做法会影响公共部门和私营部门的准确性。 “在事件响应中没有可采性要求,” Kovar说,“但是仍然需要很高的准确性。” 例如,无法报告是否泄露了客户的社会保险号可能会对监管部门造成严重影响,从而造成严重的金钱损失。

In the public sector, Kovar adds, accuracy matters apart from whether a case goes to trial: quality data delivers quality leads. Users with little or no training run a high risk of missing or misinterpreting evidence, including interpreting non-evidence as evidence.

Kovar补充说,在公共部门,准确性与案件是否要审理无关:质量数据可提供质量线索。 未经培训或未经培训的用户冒着丢失或曲解证据(包括将非证据解释为证据)的高风险。

自动化和验证的未来 (The future of automation and validation)

Entering a new decade, automation is leveling up. Artificial intelligence can identify many forms of abusive content before a human ever has to set eyes on it, and “field forensics” tools can extract certain forms of content — text messages, call logs, etc. — without their users having to send a device to a lab.

进入新的十年,自动化水平不断提高。 人工智能可以在人类不得不目击之前识别出多种形式的虐待性内容,“现场取证”工具可以提取某些形式的内容(文本消息,通话记录等),而无需用户发送设备去实验室

In the first instance, AI is used in one of two ways: to develop probable cause for a search warrant, and to find enough evidence of crimes to bring charges.

在第一种情况下,以两种方式之一使用AI:开发可能的搜查令原因,以及找到足够的犯罪证据提起诉讼。

In the second, a field forensics tool can deliver critical leads in the early stages of an investigation. A forensically sound way to find the dealer who supplied the fatal opioid dose, the pimp who is trafficking women and girls, or the child predator grooming a victim can be the first link in a chain of custody that many police officers didn’t previously have.

第二,现场取证工具可以在调查的早期阶段提供关键线索 。 寻找提供致命阿片类药物剂量的经销商,贩运妇女和女童的皮条客,或掠夺者为受害者提供帮助的捕食者,可能是一种法医上的合理方法,可能是许多警官以前没有的监护链中的第一个链接。 。

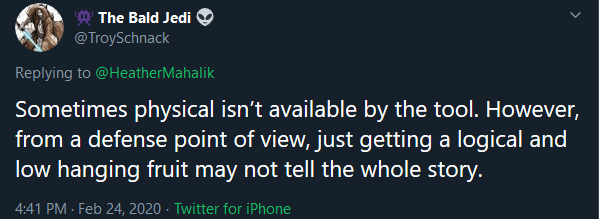

There’s still just one problem: automation is so convenient, it may return what appears to be a complete story, yet still — as forensic examiner Troy Schnack observed in a recent tweet — manage to miss the full picture.

仍然只有一个问题:自动化是如此便利,它可能会返回一个完整的故事,但是,正如法医考官Troy Schnack 在最近的一条推文中所观察到的那样,仍然设法遗漏了全部情况。

Easy access to evidence can lead an overworked investigator to form a premature conclusion. Passing this information along to a likewise overworked forensic examiner may lead to evidentiary findings that support the conclusion — confirmation bias — without additional testing.

容易获得证据可能导致过度劳累的研究者得出过早的结论。 将此信息传递给同样工作过度的法医检查人员,可能会得到支持结论的证据发现(确认偏差),而无需进行其他测试。

Oftentimes, Kovar says, the only way to prevent a miscarriage of justice is for someone to pay the money for a deep dive. The newer the technology, the more expensive the process.

科瓦尔说,通常情况下,防止流产司法的唯一方法是让某人支付深潜费用。 技术越新,过程越昂贵。

Of course, this describes all technology at some point. Kovar points to the example of “breaking new ground” in using, say, an Amazon Echo or an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) as evidence. To get anything new admitted in court, he says: “You have to trace it back to existing capabilities, reduce a UAV to familiar component parts [such as] a network port or Linux kernel.” From there, even if no tool exists to process the device, showing, the process used to obtain the data can help.

当然,这在某种程度上描述了所有技术。 Kovar指出了使用“亚马逊回声”或无人驾驶飞机(UAV)作为证据的“突破性进展”的例子。 为了使任何新的东西在法庭上得到认可,他说:“您必须将其追溯到现有功能,将UAV简化为熟悉的组成部分,例如网络端口或Linux内核。” 从那里开始,即使不存在用于显示设备的工具,用于获取数据的过程也会有所帮助。

Then again, Kovar adds, sometimes the technology itself makes it more difficult to explain how an examiner reached their conclusions. “How do you understand how the AI or machine learning made its decision?” he says. Opacity can undermine the evidence needed in a court of law — and the scientific foundations of digital forensic science.

再者,科瓦尔补充说,有时技术本身使解释审查员如何得出结论更加困难 。 “您如何理解AI或机器学习如何做出决定?” 他说。 不透明会破坏法院所需的证据以及数字法医学的科学基础。

forensic horizons seeks to ask the questions that may be getting lost in the pressure to do more with less:

法医视野试图提出以下问题:在事半功倍的压力下可能会迷失:

- How is the AI within a forensic tool trained, and how do we ensure its validity? 法医工具中的AI如何进行训练,我们如何确保其有效性?

- When (if ever) is it appropriate to use digital evidence as intelligence? 什么时候(如果有的话)使用数字证据作为情报是合适的?

- As the technology or methods behind tools become harder to explain, how might admissibility standards be impacted? 随着工具背后的技术或方法变得越来越难以解释,可采性标准将如何受到影响?

- How can you justify digging deeper when a tool returns compelling “good enough” evidence to build a case? 当工具返回有说服力的“足够好”的证据来建立案例时,您如何证明更深入地挖掘呢?

- What might the criminal investigation and e-discovery worlds learn from one another? 刑事调查和电子发现世界可能会从中学到什么?

- What is vendors’ role in shaping the assumptions we make about digital evidence? 供应商在塑造我们对数字证据所做的假设时起什么作用?

- And how can you make quality assurance work for your lab? 以及如何使质量保证在您的实验室中发挥作用?

Our team consists of experienced forensic examiners, legal experts, journalists, and others with an interest in testing technology against the definition of “forensic”: “belonging to, used in, or suitable to courts of judicature or to public discussion and debate; relating to or dealing with the application of scientific knowledge to legal problems.”

我们的团队由经验丰富的法医审查员,法律专家,新闻工作者和其他对根据“法医”的定义测试技术感兴趣的人员组成:“属于,使用或适合司法法院或公众讨论与辩论; 有关或将科学知识应用于法律问题的处理。”

By thinking critically about both the tech we use in our everyday lives, the tech we use to investigate it, and the legal, legislative, and regulatory underpinnings of it all, we hope to inspire an ongoing conversation that will lead to better policies and processes for all, including:

通过认真考虑我们在日常生活中使用的技术,用于调查的技术以及所有这些技术的法律,立法和法规基础,我们希望激发持续不断的对话,以促成更好的政策和流程对于所有人,包括:

- Better quality-assurance habits within forensic labs. 法医实验室中更好的质量保证习惯。

- Aid for attorneys who want to ask the right questions both in and out of court. 协助想在法庭内外提出正确问题的律师。

- Clearer, simpler language used to describe tech to less technical jurors and judges. 用于向技术含量较低的陪审员和法官描述技术的更清晰,更简单的语言。

Join us on the horizon and subscribe!

加入我们的行列并订阅!

数字取证

1898

1898

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?

被折叠的 条评论

为什么被折叠?